The Perils of Materialism

“Materialism can never offer a satisfactory explanation of the world. For every attempt at an explanation must begin with one’s forming thoughts about phenomena. Thus, materialism starts with the thought of matter or of material processes. In so doing, it already has two different kinds of facts on hand: the material world and thoughts about it. Materialism attempts to understand the latter by seeing them as a purely material process. It believes that thinking occurs in the brain in the same way as digestion occurs in the animal organism. Just as it ascribes mechanical and organic effects to matter, materialism also assigns to matter the capacity, under certain circumstances, to think. But it forgets that all it has done is to shift the problem to another location. Materialists ascribe the capacity to think to matter rather than to themselves. And this brings them back to the starting point. How does matter manage to think about its own existence? Why does it not simply go on existing, perfectly content with itself? Materialism turns aside from the specific subject, our own I, and arrives at an unspecific, hazy configuration: matter. Here the same riddle comes up again. The materialist view can only displace the problem, not solve it.”

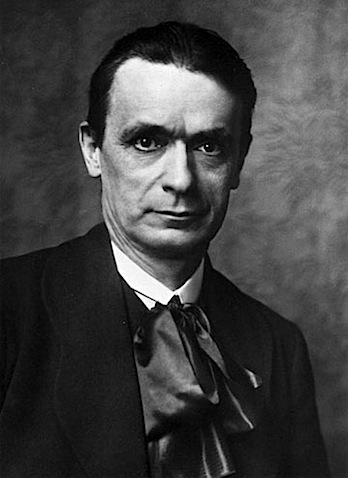

–Rudolf Steiner (Croatian-born Austrian Mystic, Occultist, Social Philosopher, Architect and Founder of Anthroposophy, 1861-1925)

The Philosophy of Freedom, a.k.a. The Philosophy of Spiritual Activity (1921), a.k.a. Intuitive Thinking as a Spiritual Path (1995)

Creation Unfolding

“What moves thoughts through the mind is precisely what moves the clouds across the sky. All are a part of the same continuum of creation unfolding.”

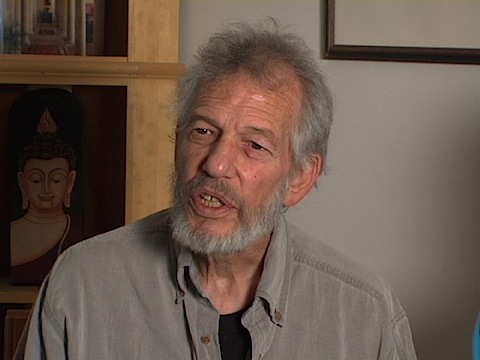

–Stephen Levine (American Poet, Writer and Spiritual Teacher Best Known for His Work on Grief, Death and Dying, 1937-)

“Turning Toward the Mystery: A Seeker’s Journey” (Stephen Levine)

Think Lightly of Yourself

“Think lightly of yourself and deeply of the world.”

–Miyamoto Musashi (a.k.a. Shinmen Takezō, a.k.a. Miyamoto Bennosuke, a.k.a Niten Dōraku, Japanese Samurai, Swordsman and Founder of the Hyōhō Niten Ichi-ryū or Niten-ryū style of Swordsmanship and Author of The Book of Five Rings (五輪書 Go Rin No Sho), on Strategy, Tactics, and Philosophy, c.1584-1645)

“The Book of Five Rings (Shambhala Classics)” (Miyamoto Musashi)

Aligning Your Thoughts, Words and Actions

“Your thoughts should agree with your words, and the words should agree with your actions. In this world people think one thing, say another thing, and do something else. This is horrible. This is crookedness.”

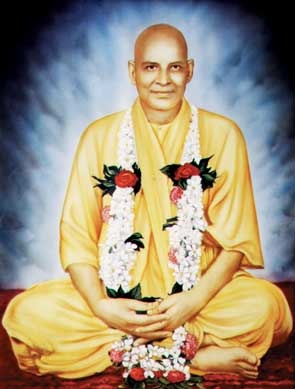

–Sri Swami Sivananda (Indian Physician and Spiritual Teacher, 1887-1963)

The Universal Flux of Events and Processes

“Indeed, to some extent it has always been necessary and proper for man, in his thinking, to divide things up, if we tried to deal with the whole of reality at once, we would be swamped.

However when this mode of thought is applied more broadly to man’s notion of himself and the whole world in which he lives, i.e. in his world-view then man ceases to regard the resultant divisions as merely useful or convenient and begins to see and experience himself and this world as actually constituted of separately existing fragments. What is needed is a relativistic theory, to give up altogether the notion that the world is constituted of basic objects or building blocks.

Rather one has to view the world in terms of universal flux of events and processes.”

–David Bohm (American-born Theoretical Physicist and Philosopher, 1917-1992)

Thought and Speech

“Everyone who lives any semblance of an inner life thinks more nobly and profoundly than he speaks.”

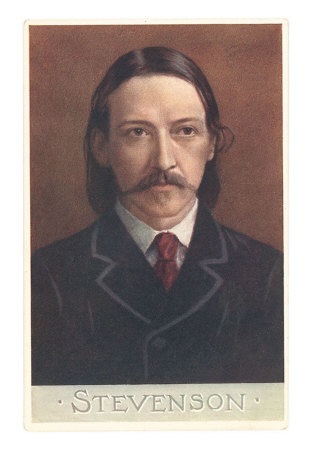

–Robert Louis Stevenson (Scottish Writer, 1850-1894)

Your Thoughts Are Your Key

“It isn’t what you have or who you are or where you are or what you are doing that makes you happy or unhappy. It is what you think about it.”

–Dale Carnegie (American Educator and Author, 1888-1955)

Integrating Reason and Intuition

“People with high levels of personal mastery do not set out to integrate reason and intuition. Rather, they achieve it naturally- as a by- product of their commitment to use all the resources at their disposal. They cannot afford to choose between reason and intuition, or head and heart, any more than they would choose to walk on one leg or see with one eye.”

–Peter Senge (American Expert on Organizational Development and Head of the Center for Organizational Learning at the MIT Sloan School of Management, 1947-)

Thinking, Feeling, Doing and Intuiting

Paul Brunton had an enormous influence on on my early life. Sometimes a controversial figure, he had many genuine insights, wrote some beautiful books and was one of the people responsible for introducing Ramana Maharshi and Sri Aurobindo to the West.

Here is something that I hope you will like:

“The four sides of the pyramid of being – thinking, feeling, doing, and intuiting – must be drawn together, properly developed, and held together in proper balance. The inclination to fragment the self is the inclination to follow the easiest path, not the needed path. The whole person needs both developing and balancing; part of it cannot be left safely in neglect while the other part is intensively cultivated.

The philosophic goal is to be spiritually aware in all parts of the psyche, with the complete life as the final result. The aspirant must engage the whole of his person in the work of self-illumination, and not merely a part of it. If only a piece of it is active in this work, only a piece can get illumined or inspired. Even meditation itself – so important for the awakening of intuition – is only a part, and a limited part, of the Quest. Wholeness must be the ideal, if the whole of the Overself’s light is to be brought forth and shone down into every day’s living, thinking, feeling, and being. Anything less yields a lesser result. And if the whole is not held properly, is unbalanced, it yields a distorted result.”

–Paul Brunton (a.k.a. Raphael Hurst, English Philosopher, Traveler, Spiritual Teacher and Author, 1898-1981)

Counterfactual Thinking

Most of us have experienced the “I should have,” “I could have,” “If only I” and “I would have” moments. Times when we lament our missteps. We say to ourselves that we should have invested in a certain stock, should have married Agnes or become a doctor instead of a cab driver. Though it can be positive, for some people this kind of thinking becomes so pervasive that they simply cannot take any action in the present. So anything that we can learn about this process will likely help a great many people.

We refer to this process in which we evaluate how we would do things differently, as “counterfactual thinking.” Though it can be positive, and help us learn from our mistakes, it is a common psychological mechanism that causes us to harbor feelings of disappointment and regret. For some people this kind of thinking becomes so pervasive that they simply cannot take any action in the present. So anything that we can learn about this process will likely help a great many people.

A common research strategy in the study counterfactual thinking, is to have people read stories in which the main character makes decisions that will ultimately doom him or her to failure. Researchers then ask them how they would have done things differently.

But this method may not provide a complete picture of this mental process. New research published in the June issue of Psychological Science, which is a journal of the Association for Psychological Science, shows that our counterfactual thinking may be markedly different when we are actually experiencing failure rather than reading about someone else’s.

In a series of experiments, Vittorio Girotto of the University luav di Venezia in Venice, Italy and his colleagues attempted to demonstrate and explain the differences in counterfactual thinking between actors who actually experienced the problem and readers who just read about it.

The experimental subjects were divided into two groups:

- Actors who were asked to participate in a game in which they could win a reward by solving a math problem. They were then asked to choose one of two sealed envelopes: One was said to contain a difficult problem, and one supposedly contained an easy problem. In reality, both envelopes contained a problem that was nearly impossible to solve in the allotted time. Once the actors failed, they were asked to write at least one way in which things would have been better for them.

- In the second group, “Readers” read a story with a protagonist who faced the same choice and ended with the same negative outcome as the subjects did in the actor condition. Like the actors, readers were required to write at least one way in which things would have been better for the protagonist.

The readers and actors were very different in their counterfactual thinking. Readers tended to undo the protagonist’s choice to tackle the problem, while actors changed the way in which they tried to solve the problem. So a reader would say, “I should have picked another envelop,” while the actor would ask if he could use a calculator.

These results run counter to previous theories of counterfactual thinking. It was assumed that people who read a story construct the same counterfactuals as people who experienced the events described in the story. It was also believed that actors tend to avoid self-blame at all costs when thinking of alternatives. Instead, the actor-reader differences emerged even in conditions in which actors’ decisions made the best decisions that they could. The researchers said,

“Actors and readers produce different counterfactuals because they rely on different information, not because they have different motivations.”

In both cases, “what might have been” thinking can be stressful.

This research confirms something that we have been teaching for years:

Learn to detach from your aims and desires: you need passion and purpose. But you do not need the third “P:” Pain

Liberate yourself from the past: Healing, Meaning and Purpose has a whole section on novel ways to get rid of some of the “stuff” that most of us carry around in our bodies, our minds and our subtle systems.