Ancient Behavior

Your humble reporter has had a longstanding interest in human evolution. Not just in terms of understanding where we came from, but also where we may be going. There is also the fascinating question of re-capitulation: do children in a few years go through the same kinds of developmental phases that our ancestors went through over thousands of years?

One of the Big Questions has been “When did early humans begin to think and behave in some of the same ways that we do?”

This is often called “behavioral modernity” and one of its measures is in the appearance of objects used purely as decoration or ornamentation: items that are widely regarded as having symbolic rather than practical value. Their visual and symbolic impact are greatly increased if they are displayed on the body as necklaces, pendants, earrings or bracelets or attached to clothing. The appearance of ornaments like these may well be linked to a growing sense of self-awareness and identity amongst humans. Presumably any symbolic meanings would have been shared by members of the same group.

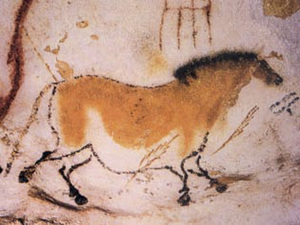

Amongst the oldest known symbolic ornaments in Europe are perforated animal teeth and shell beads that have been dated to the Upper Paleolithic era, that is no more than 40,000 years ago. These finds are associated with both modern human and late Neanderthal sites. Together with cave paintings and engravings they offer the strongest indications that European societies of those times were capable of abstract thinking. They began to be able to symbolize their ideas without relying on obvious links between a meaning and a sign. But there is now a growing body of evidence to indicate that symbolic cultures consisting of engravings, personal ornaments and systematic use of beads had emerged much earlier in Africa.

In a recently published paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences archaeologists from Morocco, the United Kingdom, France and Germany, have shown that some of the earliest examples of bead making may date back as far as 82,000 years ago in North Africa.

The evidence is in the form of deliberately perforated Nassarius marine shells, some still smeared with red ochre, that were found deep down in the Grotte des Pigeons at Taforalt in northeastern Morocco. A multidisciplinary team has been working in this massive limestone cave for the past five years. The finds come from a sequence of ashy deposits that have been independently dated by scientists at Oxford and in Australia using four different techniques that allow them to make accurate age estimates for the layers containing the shells.

The shell beads have been studied by experts in France who have confirmed that they are a shallow marine species gathered from the beach, which even in the past lay more than 30 miles from the cave. Once collected, the dead shells were then probably perforated, painted with ochre and used as personal ornaments. Some of the beads show microscopic wear patterns that would suggest they were suspended from a necklace or bracelet. The application of red pigment may have been intended to give them added visual symbolic value. There’s not much doubt that this was part of a very deliberate cultural practice.

This finding suggests that forty thousand years earlier than anyone knew, there were people on this planet who could think in symbols, and engaged in rituals that were meaningful for them.

Time to re-write those history books again!

“Why is it so painful to watch a person sink? Because there is something unnatural in it, for nature demands personal progress, evolution, and every backward step means wasted energy.”

–August J. Strindberg (Swedish Dramatist, Novelist and Poet, 1849-1912)

“What we usually call human evolution is the awakening of the Divine Nature within us.”

–“Peace Pilgrim” (a.k.a. Mildred Norman, American Peace Activist, 1908-1981)

How Doctors Think. Or Not.

I recently reviewed a fascinating book at the Amazon website. It is called “How Doctors Think,” and it was written by the ever-thoughtful Jerome Groopman from Harvard.

To save you having to look through all the reviews to find what I said, I thought that it would be useful to say something about the book and why I have some reservations about Jerome’s analysis.

Most doctors are highly educated, hard working people who most of the time try to do their best. Yet in our blame culture there are places in America where you can’t get a specialist to treat you: they have all been driven out of business by lawyers representing unhappy clients. The question of why this has come to pass has occupied the minds of the American medical profession for three decades.

Jerome believes that the key problem is that doctors make the same kind of errors in thinking that the rest of us do. We all – and not just doctors – jump to conclusions; believe what others tell us and trust the authority of “experts.” Clinicians bring a bundle of pre-conceived ideas to the table every time that they see a patient. If that have just seen someone with gastric reflux, they are more likely to think that the next patient with similar symptoms has the same thing, and miss his heart disease. And woe betides the person who has become the “authority” on a particular illness: everyone coming through his or her door will have some weird variant of the disease. As Abraham Maslow once said, “If the only tool you have is a hammer, you tend to see every problem as a nail.” To that we have to add that not all sets of symptoms fall neatly into a diagnostic box and that uncertainty can cause doctors and their patients to come unglued.

Up to this point the book is very good as far as it goes but I do not think that the analysis is complete.

I have taught medical students and doctors on five continents, and this book does not address some of the very marked geographic differences in medical practice and the book is “Americano-centric.”

The first point is that the evidence base in medicine is like an inverted pyramid: a huge amount of practice is still based on a fairly small amount of empirical data. As a result doctors often do not know want they do not know. They may have been shown how to do a procedure without being told that there is no evidence that it works. As an example, few surgical procedures have ever been subjected to a formal clinical trial. Although medical schools are trying to turn out medical scientists, many do not have the time or the inclination to be scientific in their offices. In day-to-day practice doctors often use fairly basic and sometimes flawed reasoning. A good example would be hormone replacement therapy. It seemed a thoroughly good idea. What could be better than re-establishing hormonal balance? In practice it may have caused a great many problems. Medicine is littered with examples of things that seemed like a good idea but were not. Therapeutic blood letting contributed to the death of George Washington, and the only psychiatrist ever to win a Nobel Prize in Medicine got his award for taking people with cerebral syphilis and infecting them with malaria. The structure of American medicine does not support the person who questions: consensus guidelines and “standards of care” make questioning, innovation and freedom very difficult. A strange irony in a country founded on all three.

The second major factor in the United States – far more than the rest of the world – is the practice of defensive medicine: doctors have to do a great many procedures to try and protect themselves against litigation. This is having a grievous effect not only on costs, but also on the ways in which doctors and patients can interact.

Third is the problem of demand for and entitlement to healthcare. We do not have enough money for anything: but what is enough if the demand for healthcare continues to grow as we expect? And if people are being told that it is their right to live to be a hundred in the body of a twenty year-old? Much of the money is directed in questionable directions. There are some quite well known statistics: twelve billion dollars a year spent on cosmetic surgery, at a time when almost 40 million people have no health insurance. There are some horrendous problems with socialized medicine, but most European countries have at least started the debate about what can be offered. Should someone aged 100 have a heart transplant? Everyone has his or her own view about that one, but it is a debate that we need to have in the United States.

Fourth is the impact of money on the directions chosen by medical students and doctors starting their careers. Most freshly minted doctors in the United States have spent a fortune on their education, so they are drawn to specialties in which they can make the most money to pay back their loans. In family medicine and psychiatry, even the best programs are having trouble filling their residency training programs. Many young doctors are interested in these fields, but they could die of old age before they pay off their loans.

Fifth is the problem of information. It is hard for most busy doctors in the United States to keep up to date on the latest research, and many are rusty on the mechanics of how to interpret data. So much of their information comes from pharmaceutical companies. Many of the most influential studies have been conducted by pharmaceutical companies, simply because they have the resources. But there have been times when data has therefore appeared suspect. Industry is not evil, but companies certainly hope that their studies will turn out a certain way, and the outcome of any study depends on the questions asked and the way in which the data is analyzed. And like any collection of people, it is easy to fall into a kind of groupthink. There are countless examples of highly intelligent individuals who all missed the wood for the leaves.

Another related problem is that many scientists are now also setting up companies to try and profit from the discoveries that they have made in academia. Most are working from the highest motives, but sometimes there are worries about impartiality. So once again, the unsuspecting physician may add data to the diagnostic mix without knowing its provenance. There have recently been a number of high profile examples of that.

I ended my review by saying that I hope that every doctor and patient in America should read it, and I stand by that, with the caveats and comments that I have added to the mix.

Thinking Speed, Mood and Optimism

There’s a very interesting article at the Mixing Memory blog. It’s one of the blogs that I highlight in the “What I’m reading” section. The articles highlights some recent research by Emily Pronin and Dan Wegner from Princeton and Harvard respectively, entitled “Manic Thinking: Independent Effects of Thought Speed and Thought Content on Mood.”

It’s about an intriguing issue. People who have a manic illness have an acceleration of thinking processes together with elevated mood and energy level. Mania is also associated with racing thoughts grandiose or creative ideas, fast, uninterruptible speech, aimless pacing, irritability and an over-involvement in pleasurable activities, together with a loss of impulse control.

It may sound great, and initially people are often very happy to be manic. But after a while it can give way to exhaustion or the realization that some of their choices have been unwise. I once knew someone who was driving a brand new BMW – that she could definitely not afford – at over 120 miles an hour, the wrong way down Interstate 95. That’s when the police became involved, and they immediately realized that she was not a villain, but a very sick person who could have killed herself and a ton of other people.

The researchers they had a group of college undergraduates read a series of 58 emotion-inducing statements out loud, and to do it at either a fast or slow pace. The statements are emotionally neutral at the beginning and then become progressively more emotionally positive or negative. The idea is that reading a series of progressively more positive or negative statements will affect the reader’s mood. The letters in the statements were presented one at a time, either for 40 milliseconds per letter (“fast thinking” condition) or 170 milliseconds per letter (“slow thinking”). A pilot study indicated that the 40 milliseconds per letter reading time were about twice the normal reading speed for college undergraduates and 170 milliseconds were about half the normal speed. The time between statements also varied, with only 320 milliseconds between statements in the “fast condition” and 4 seconds between statements in the “slow condition.”

After reading all 58 statements, the participants were asked to answer a series of questions designed to assess their mood, energy level, feelings of power, creativity and inspiration. There were also questions to evaluate “grandiosity or inflated self-esteem,” together with their own perceptions of their speed of thought.

Subjects in the “fast thought” condition reported faster thought speeds than those in the “slower” condition. As predicted, faster thought speeds affected mood and mania-related feelings, participants in the fast thought condition reported being happier, had higher energy levels, experienced greater senses of power and creativity, and higher levels of grandiosity (though self-esteem did not differ between conditions). What is important, is that these effects were independent of the mood manipulation (positive or negative statements). Here is a graph from the paper presenting the effects of slow and fast thinking as a function of the type of sentence:

This study has some important implications. Thinking more quickly produces elevations of mood and self-perception that can smetimes be similar to those of very mild mania. I have seen this happen frequently when people have been up all night: the bright lights of morning and a few cups of coffee make them appear mildly manic. For a time they do in fact impress with their creativity and mastery not only of details, but of the “Big picture.” But as time goes on, much of their thinking turns out to be not altogether logical.

The study also raises the possibility that some manic symptoms may be produced by thinking. There is an old term from the psychoanalytic literature called “manic defense,” in which people use manic-like symptoms to protect themselves – or more accurately their ego structures – when under stress.

I have spent most of my life with people who think very quickly and accurately. Most also express themselves very well: both succinctly and fluently. But all have also known the importance of stopping for a while after a brainstorming session, so that we can see if our ideas have really born fruit, or if they just seemed a good idea at the time.

There is no question that moving and speaking more quickly can elevate our mood. It is no surprise that it has little impact on self-esteem. It is becoming more and more clear that self-esteem follows from genuine achievement. Boosting artificially is difficult, with one exception: when people have every reason to have decent self-esteem, but instead they keep feeling bad, as if they have a kind of leaky bucket as my friend the psychiatrist Stephen Preas calls it.

I remember an experiment in which an investigator was experimenting with ether. During one of his sessions he had a deeply felt mystical experience in which he was sure that he suddenly understood the whole of nature and reality. He immediately wrote it down so that he could show the world The Secret.

When he came back down to earth, he looked at what he had written, “The world is like a fish…”

“The world that we have created is a product of our thinking. It cannot be changed without changing our thinking.”

–Albert Einstein (German-born American Physicist and, in 1921, Winner of the Nobel Prize in Physics, 1879-1955

)

“Some would sooner die than think. In fact, they often do.”

–Bertrand Russell (Welsh Mathematician, Philosopher, Pacifist and, in 1950, Winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature, 1872-1970)

“Most people can’t think, most of the remainder won’t think, the small fraction who do think mostly can’t do it very well. The extremely tiny fraction who think regularly, accurately, creatively, and without self-delusion. In the long run, these are the only people who count.”

–Robert Heinlein (American Writer, 1907-1988)

Madness and Genius Revisited

I must have heard a thousand times that there’s a fine line between genius and insanity. I have talked before about the possible link between the two through schizotypal personality disorder. It is quite well known that there are two living Nobel Prize winners who have a diagnosis of schizophrenia and many more who have first-degree relatives with it.

There is some very interesting research in the current issue of the Journal of Clinical Investigation from a team of scientists at the National Institutes of Health’s (NIH) National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH).

In the latest installment of a story that has been unfolding over the last three decades, they report on their findings concerning a human gene for a master switch in the brain called DARPP-32. Most people inherit a version of a gene that optimizes their brain’s thinking circuitry, yet paradoxically also appears to increase risk for schizophrenia, an illness marked by impaired thinking. The main kinds of thinking involve reasoning, abstraction and creativity.

Over the last two decades, studies in animals, most notably by Nobel Laureate Paul Greengard at Rockefeller University, have established that DARPP-32 in the striatum switches streams of information coming from multiple brain chemical systems so that the cortex can process them. Both the neurotransmitter that DARPP-32 works through – dopamine – and the chromosomal site of the DARPP-32 gene have been implicated in schizophrenia.

The NIMH researchers in this new study have identified a common version of the gene and showed how it impacts the way in which two key brain regions exchange information, so affecting a range of functions from general intelligence to attention.

To understand DARPP-32’s role in the human brain, they used genetic, structural and functional magnetic resonance imaging and also post-mortem studies to identify the human gene’s variants and their functional consequences.

Seventy five percent of subjects had the most common version of the gene, which boosted the activity of circuits in the prefrontal cortex of the brain. This region is the major filter, controller and processor of cognitive information. When active, it increases structural and functional connections and our performance on tasks that involve thinking. It almost certainly does so by increasing gene expression. In 257 affected families, people with schizophrenia were also more likely to have this common version of the DARPP-32 gene.

DARPP-32 appears to shape and control a circuit running between the striatum and prefrontal cortex. The circuit affects key brain functions implicated in schizophrenia, such as motivation, working memory and reward-related learning.

The senior investigator is Daniel Weinberger, who had this to say,

"Our results raise the question of whether a gene variant favored by evolution, that would normally confer advantage, may translate into a disadvantage if the prefrontal cortex is impaired, as in schizophrenia. Normally, enhanced cortex connectivity with the striatum would provide increased flexibility, working memory capacity and executive control. But if other genes and environmental events conspire to render the cortex incapable of handling such information, it could backfire — resulting in the neural equivalent of a superhighway to a dead-end."

Although several groups of researchers have looked for the possible clinical relevance of DARPP-32, they have had much success. This study shows a strong connection between the molecule and human cognition and also, perhaps, with schizophrenia.

What is also interesting about this finding is that it helps provide us with a mechanism by which environmental stress could lead to cognitive problems.

Apart from the uninformed tirades of Tom Cruise, I see a lot of opinion pieces on websites and YouTube expressing the opinion that psychiatry is baseless, ostensibly because there is no science behind it. By anyone’s standards, this is high level science utilizing a series of state-of-the-art approaches. And another piece of evidence that psychiatry is becoming more science than art, linking the mind, the brain and the environment into one harmonious whole.

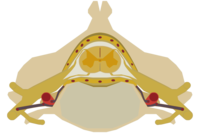

Does the Spinal Cord Think?

In recent years we have become very interested in the ever-increasing evidence there are large complex neural networks outside the brain and autonomic nervous system. The main ones are in the intestine and the heart. These systems are so complex and well organized that some people have talked about us having a “brain” in the heart and another in the intestine. This may be a bit of an over-statement. For instance the cerebellum at the back of the brain is large and highly complex, but is so arranged that it probably cannot generate conscious experience. That particular trick needs a cerebral cortex that self-organizes, recruits new systems when necessary for some particular task and generates vast oscillations that are modulated by genes and the environment.

Now new research has shown that the spinal cord has some of those same properties that we associate with the cerebral cortex. This groundbreaking work has just been published in the journal Science, and the entire paper is available here.

So why the excitement and interest? It often astonishes me how many students who come to my lectures seem not to have a curiosity gene. And there is so much about which we should be curious. Despite the billions spent on research there is still a great deal about the human body that is not understood at all. Not small esoteric things, but huge questions.

For instance how can some people think and communicate even if most of the brain is destroyed by disease? On the other hand some people are incapacitated by the smallest lesion. I’ve taught neurology for years, in particular the art of neurological examination. I was trained by some of the best in the world, so I know how to look for subtle neurological signs. Yet I’ve seen a great many inexplicable things: I saw someone come to autopsy who had no neurological signs, but had a tumor occupying more than half of the dominant hemisphere of the brain.

Here’s another puzzle: we don’t know how humans are able to move. Our muscles are controlled by thousands of nerve cells in the brain, spinal cord and peripheral nervous system. This entire complex system must work as a whole in order to successfully generate a single motion. Yet how quickly do most children learn to stand and walk. The new research has shown that the spinal cord is not a passive signal conductor, but has instead shown that spinal neurons, while engaged in the network activity underlying movements, show irregular firing patterns similar to those seen in the cerebral cortex. Even if we repeat a certain motion with high accuracy, the nerve cells involved never repeat their activity patterns. Just the same as happens in the cerebral cortex.

This is yet more evidence to suggest that “thinking” does not only go on in the brain. It makes sense to think of the major systems – heart, intestine and spine – as key components of the subliminal, pre-conscious mind. Some people like the term subconscious, but that runs into the confusing problem of mixing up the terms subconscious and unconscious.

I talk about some of these differences and how to work these different parts of yourself in the book and CD series Healing, Meaning and Purpose.

Chiropractors have been telling us for years that the spinal cord is a lot more than just a relay system. It looks as if they may have been correct.

If you are interested in following up on my comments about what it takes for a neural network to generate conscious experiences, you may be interested in having a look at my review of the excellent new book Rhythms of the Brain by Gyorgy Buzsáki. and

Acupuncture Points

The Pacific College of Oriental Medicine publishes a newspaper entitled Oriental Medicine, that carries a great many interesting articles mainly written by practicing acupuncturists. In the current issue there is a nice article entitled “What are Meridians and Points?” by Iona Marsaa Teeguarden a therapist who has developed some very interesting acupressure techniques for dealing with an array of problems. This is a very interesting topic to me: you may have seen some of those pictures of acupuncture points that look like tramlines traversing the body.

Over the last few years I’ve read everything about the acupuncture points that I could get my hands on. If it’s in one of the ten or twelve languages that I can read, then I’ve probably got a reprint of the paper, and people have been kind enough to send me translations of at least parts of papers in Chinese, Japanese and Korean. Some of the research has been excellent, and some less so.

The first point (ha ha…), often controversial when I am talking to classically trained acupuncturists, is that although some of the large well-known acupuncture points are usually in the same place in different individuals, many of the lesser known points are not. Of the 361 main named acupuncture points only a couple of dozen seem to be fixed on the body. Most of the rest can be some way off from the pictures in books. I learned that first when I was an apprentice in London, and then during my studies in China. The top Chinese acupuncturists search for the right points to use. It’s one of the reasons why modern Chinese acupuncturists have identified over a thousand “extra points.”

Although people usually talk about “meridians” joining the acupuncture points together, the Chinese usually refer to them as “channels and collaterals.”

There does not seem to be any neurological or vascular structure at the site of an acupuncture point. Taken together with he fact that acupuncture points tend to be tender and to have characteristic electrical properties, both of which get better with treatment, suggests that they are functional rather than structural entities. Most experienced acupuncturists have noticed that the points vary not just with treatment, but also with mood, the weather and in women, during the menstrual cycle.

In the late 1930s, a French physician named Niboyet was probably the first to find indications that the main acupuncture points have lowered electrical resistance compared with surrounding skin. Some other studies (1, 2, 3, 4, 5.)have provided some support for these findings, although it is difficult to known precisely what to make of the finding that these areas of reduced electrical resistance can also be located on fresh but not dried cadavers. Some people have invoked some mechanism involving electrolytic fluxes along connective tissue or fascial planes of the body. But that’s all just speculation backed by some research correlating acupuncture points and fascial planes.

An additional problem for simple electrical models is that some of the acupuncture points also respond to polarized light, which would be odd if the primary mechanisms of acupuncture points were electrical.

Another set of experiments sought to exploit the phenomenon of “propagated needle sensation.” If acupuncture is done well, then this happens very frequently. It is a subjective sensation of warmth, heaviness, numbness or bursting, that moves at between 1 and 10 centimeters per second, which is much slower than a nerve impulse. This sensation moves along the proposed channels along which the Qi is supposed to flow. But this is the interesting bit: the sensations are not related to any known neurological pathways. The precise nature of this propagated needle sensation remains elusive, with reports of it being interrupted by chilling, local anesthetics and mechanical pressure, whilst it has also been shown to travel to phantom limbs in amputees.

Attempts have been made to trace out acupuncture points and their associated channels by the use of radioactive tracers and by measuring electrical propagation along the channels. 99-Technetium has been the most widely used, and it has been claimed that the tracers diffuse from acupuncture points along the classical acupuncture channels, whilst tracer injected at non acupuncture points diffuses without showing any such linear pattern. The speed of the linear migration of the tracer injected into acupuncture points was accelerated by the use stimulation of appropriate acupuncture points.

If we cannot find anything anatomical at acupuncture points, and they clearly change place and character as the person changes. Then what do the Chinese have to say about the points and the channels?

They say that the channels are there to distribute Qi, and that the acupuncture points are the control points of the channels. The traditional theory is that Qi flows in response to thoughts and emotions. Perhaps thoughts and emotions have effects on muscle contraction and that pushes the Qi along, but I thin that we have to step away from the physical body. I can well remember one of the first people whom I ever treated. I gently needled a “Liver point” on her foot, and she felt the sensation in her eye on the same side of the body. There is no known neurological connection between the foot and the eye on the same side. But in Chinese medicine, the Liver channel terminates in the eye on the same side of the body. The theory of fascial planes can also not explain that. Neither can the observation that many of us have made in the clinic. In some people, acupuncture reveals their entire acupuncture system: the channels become red.

Even when acupressure is used in the subtle systems around the body. I have seen a Chinese Qigong Master demonstrate this phenomenon in a paraplegic patient.

While the Master’s hands were three feet away for the body.

And that will be the topic of yet another research study.

Memes and Magical Thinking

There were so many excellent papers at this year’s British Association Festival of Science, that I still haven’t had been able to comment on all of them, but here’s another one that I found interesting for two reasons.

Bruce Hood, who is Professor of Experimental Psychology at the University of Bristol, presented an interesting paper on the near-Universality of superstitious beliefs and magical thinking. In his view people are naturally biased to accept a role for the irrational, and magical thinking is hard-wired into our brains.

Magical thinking is invaluable to an artist: being able to make new connections is the key to their creations. But it has long been argued that either rejecting or accepting magical thinking may both be potential triggers of psychopathology. I once treated a young Israeli man who, during the first Gulf War, became convinced that Saddam Hussein was personally writing the Israeli man’s name on each Scud missile. He refused to remove his gas mask, and eventually his thinking became delusional.

Bruce’s conclusion is that magical thinking and a belief in the supernatural is an evolutionary adaptation. He goes on to argue that the rabid atheists who blame organized religion for the spread “illogical thinking” and a belief in the supernatural and are just plain wrong. Instead he contends that religion may capitalize on a natural bias to assume the existence of supernatural forces.

In a world in which religious fundamentalism is something of a challenge, he had this to say:

“It is pointless to get people to abandon their belief systems because they operate at such a fundamental level that no amount of rational evidence or counter evidence is going to be taken on board to get people to abandon these ideas.”

Bruce has carried out studies to show how the brains of even young babies organize sensory information. They supply what is missing and use the information to generate theories about the world.

In adulthood, the visual centers of the brain still fill in details that are not there, as shown in common visual illusions such as the blind spot. Several years ago we did some experimental work on facial recognition, and it is remarkable how little information is needed to recognize a face: the brain supplies the missing pieces of the picture. This childhood “intuitive reasoning” persists in to adulthood and may explain many aspects of adult magical beliefs. We are programmed to see coincidences as significant and to attribute minds to inanimate objects.

One form of this is known as pareidolia in which vague and random stimuli are misperceived as recognizable patterns. Examples of this are seeing shapes in clouds or in a fire. With the new information from the European Space Agency, perhaps we could include seeing the Face on Mars.

Professor Hood used an interesting example. He offered members of the audience the chance to wear a sweater, for which he would pay them a sum of money. They were all happy to do so, until they heard that it had supposedly belonged to a mass murderer, when suddenly there were no takers. Many said that they felt that the clothing was contaminated with evil.

But I don’t think that Bruce has taken something else into account. According to the theory of spiral dynamics, we are all mixtures of Memes. We tend to associate magical thinking with the Purple Meme. It would be very valuable to look at a person’s developmental level and to see how much he or she engages in magical thinking. Someone once said to me, “Are you superstitious?” I said, “No, but I do understand that there are many forces at work in the Universe, and we do not yet know all of them.”

Are you a magical thinker, or is it that you are aware of the unseen forces of the Universe?

“The universe is full of magical things, patiently waiting for our wits to grow sharper.” –Eden Philpotts (Indian-born English Novelist, Dramatist and Poet, 1862-1960)

Intuitive Knowing and the Real Rainman

In 1988 the Dustin Hoffman won the Academy Award for Best Actor for his portrayal of Raymond Babbit in the movie Rainman.

The character was actually inspired by a real person named Kim Peek. Now in his mid-fifties, Kim has memorized more than 11,000 books, and can read a page of any book in about ten seconds. It has recently been discovered that each of his eyes can read a separate page simultaneously, absorbing every word. He can also do instant calculations on things related to the calendar and several other very specialized topics.

He and his brain has been studied in great detail by a Dr. Darold Treffert at University of Wisconsin Medical School. It is quite different from the rest of the population. He does not have the great bridge – the corpus callosum – that connects the two hemispheres in most people. Instead he just has one solid hemisphere. The right cerebellum is in several pieces. None of this really explains his abilities, though perhaps having no corpus callosum means that the right side of his brain is freed from dominance by the left. Darold Treffert makes a good point when ha says that Kim’s father is partly responsible for his brilliance: his belief in his son and his unconditional love for him may have more to do with bringing forth his remarkable skills than the wiring of his brain.

There have been many other cases of savants who had remarkable and seemingly effortless abilities. For years now I’ve collected reports about some of them. Srinivasa Ramanujan who complied over 3000 mathematical theorems in less than four years. Vito Magniamele who at the age of 10 could compute almost instantly the square root of any large number. Then there was a six-year-old child named Benjamin Blythe, who while out walking with his father in 1826, asked, “What time is it?” After being told, he gave – accurately – the exact number of seconds that he had been alive, including the two leap years. In one of his books, Oliver Sachs, describes a pair of twins in a psychiatric hospital who are said to have below “normal” intelligence, but who amuse themselves by swapping enormous prime numbers. Even the English chess grandmaster John Nunn reported how, as a child, he could do instant calculations in his head. And, at the age of fifteen, he became the youngest undergraduate at Oxford University in 300 years. Most strong chess masters will "know" where to put the pieces, but then come up with the logical reasons later on.

These abilities: to read and memorize, to do instant calculations and to have instant deep knowledge of topics is remarkably interesting and important for all of us. If complex mathematics can be done by people who have no training or intellectual sophistication, what other gifts and talents may we have lying undiscovered within us?

These observations lead to the questions; first, can anyone do the same feats as Kim Peek? Second, where does instant mathematical information come from? Third, can anyone access it? And fourth, is this similar to the way that shamans and Babylonian mathematicians obtained their information?

In Healing, Meaning and Purpose we learn that there is powerful evidence to suggest that we do have access to a whole seam of knowledge about the world around us. The anthropologist Jeremy Narby studied shamans in the Amazonian rainforest who have found safe and effective herbal treatments among the 80,000 plants available to them. They are usually used in combinations, and to have tested all the plants and all the possible combinations would have taken hundreds of thousands of years. So it cannot have been done by trial and error. I have seen something similar in traditional Chinese herbal medicine, where combinations are invariably used, and once again, if the effective ones had been discovered by trial and error, it would have taken armies of physicians working for countless thousands of years.

I don’t expect everyone to be able to become lightning calculators. Neither would most us want to be. But there are a number of ways of getting much better at tapping this intuitive knowing. It is important to tap your intuition and to use it as the ally of your reasoning.

- Relaxation, meditation or prayer are all excellent for starting the process. Meditation to explore your inner nature may take hours a day for many years, but when we use it to improve our inner knowing, a few minutes a day is all that you need. Just long enough slightly to alter your state of consciousness

- Visualize a place that you really like that you can return to at will. I learned this trick from a shaman, and it’s immensely useful. You might remember, visualize or create a space for yourself. For instance you might like to imagine going to a beach that you like.

- Ask a question: remember that the quality of your answers is dependent on the quality of your questions. So be precise and be calm when you ask you question.

- Agree with yourself that you will take action on what you learn. And that leads me to the last point for today:

- I just got an email question about how to differentiate between an impulse and an intuition. The answer to that is your response: an impulse impels you to immediate action, an intuition gives you time to reflect and to thank the Universe for what you’ve just been told.

“At every moment there is in us an infinity of perceptions, unaccompanied by awareness or reflection. That is, of alterations in the soul itself, of which we are unaware because the impressions are either too minute or too numerous.”

–Baron Gottfried Wilhelm von Leibniz (German Philosopher and Mathematician, 1646-1716)

Risk, Reason, Intuition and Avoiding Overwhelm

The British Academy Festival of Science at the University of East Anglia has just finished, and there were a lot of interesting papers this year.

There was some impressive work on two unavoidable parts of life: risk and uncertainty. And how we cope with them. Professor Peter Taylor-Gooby, who is the Director of the Economic and Social Research Council Social Context and Responses to Risk Network (SCARR) at the University of Kent, had this to say: "There is a lot of evidence that concern about risk is directly related to lack of knowledge and the extent to which the event is dreaded…. and trust always involves emotion as well as reason."

How can we restore people’s level of confidence in themselves, in the people around them and in people in positions of authority? The answer lies in emotions instead of reason alone. This is especially true when the perceived risk is related to health, the environment, new technologies and energy.

Peter went on to say this: "The way that information about a particular risk is transmitted and interpreted by various audiences is also important in determining how people respond."

We all engage in some routine tasks without much thought. To apply your full awareness to everything that you do would quickly become exhausting. That is why we develop habits and do some things “On autopilot.” Habits are essential, and we have helped countless people by reprogramming habit patterns.

A problem can occur when you do the wrong things on autopilot and applying too much attention to things that do not require it. The first may damage a relationship: your significant other may not be best pleased to discover that you have been on autopilot during an intimate event. Applying too much attention to things that do not merit them is a good way of developing anxieties and paranoia.

With the increasing complexity of the world, and more things vying for our attention, we are all facing what I call “Overwhelm,” which is just what is sounds like. When we are tired or sick in mind, body or soul. When our subtle systems have become depleted by poor food, irregular breathing, negative people or a negative environment, any of us can become overwhelmed. People with attention deficit disorder, anxiety disorders and bipolar disorder are all more likely to suffer from Overwhelm. Many of the techniques for developing resilience that we have been discussing, are specifically designed to protect you against Overwhelm.

The key for us is to have in place a series of coping strategies that neither rely upon rationality alone or on a mixture of blind faith or hope: that is the best way to deal with growing uncertainties.

“Often you have to rely on intuition.”

-Bill Gates American Computer Genius, Businessman and Co-founder of Microsoft, 1955-

Unconscious Processing and Intuition

There is a very interesting paper in this week’s Journal Science. It is from a group working at the University of Amsterdam, and their findings are likely to turn one branch of psychology upside down. Let me explain the importance of this work, and how you can start to apply it in your own life.

What the researchers did was to divide their subjects into two groups. In the first experiment the subjects had to decide on a favorite car. One group used a conscious, intellectual reasoning approach and the other group was distracted with puzzles to keep their conscious minds busy before making the decision. When there were only four things to factor into the choice, the intellectuals did better. But when they had to choose on the basis of 12 factors the people using conscious decision-making did much worse than the people who had to make an immediate decision based on unconscious thought processes. In the second experiment shoppers were asked about their satisfaction with items that they had bought. People who bought on the basis of conscious deliberation were much happier with their choices of simple items, while the “unconscious” shoppers preferred their choices of more complex items.

Why is this so important? Since the Enlightenment, science has emphasized the benefits of conscious deliberation in decision-making, and has tended to look down on the whole notion of unconscious thought. Yet this study adds to the growing body of evidence that not only can people think unconsciously, but that for complex decisions, unconscious thought is actually superior. Conscious thought is like a bright torchlight that can only illuminate a few things at a time, and that can lead to some aspects of a problem being given undue attention.

This report supports something that many of us have been teaching for some time. Too much conscious deliberation can actually be counter-productive. Effective thinking needs us to get all the information necessary to make a decision. Then, if we are dealing with a simple decision use conscious thought. But if the decision is complex, it is best left to unconscious thought; in effect to sleep upon it. The answer then tends to appear very suddenly.

There is a secret about the way in which a great deal of progress is made: Most of the major advances in physics have come not from logical progression, but from mystical revelation: Albert Einstein and the theory of relativity, Max Planck and quantum theory, Erwin Schrödinger and wave mechanics, the list is a long one. The great Welsh mathematician and philosopher Bertrand Russell once said of Einstein, that the problem in understanding him was not a difficulty with his logic, but with Einstein’s imagination. He was able to let his mind go to places that others could not, and it came back with answers that nobody else could have conceived of. There is evidence that while most chess players spend virtually all of their time trying to calculate, strong players rely on unconscious processes for most of the game, and only calculate for short periods when their unconscious mind tells them too. There is even evidence from brain imaging studies that average players activate all the cognitive areas of the frontal lobes while playing, with some temporal lobe activity as they try to remember their lessons. By contrast, a chess master uses many regions of his brain at once, and only occasionally activates parts of his frontal lobes when calculation is required.

What this means for us is that we must not be afraid to turn complex problems over to our unconscious minds. I have also spent a great deal of time training people to get used to using their intuition, for this is really one aspect of what we are talking about here. In my book Healing, Meaning and Purpose, I have several sections on developing your intuition.

When you start learning to turn problems over to your unconscious mind, one of the most difficult things is to know when to trust it. So here are some tips:

1. Once you have an answer, now is the time to use your conscious mind to see if the answer that you’ve come up with makes sense.

2. Learn to trust yourself. That may take a little time, but if you have a problem with trusting yourself, you have something tangible to work on.

3. Always be certain that you are prepared to hear whatever answers you receive.

4. Use your intuition to evaluate your intuitions: does the answer “feel” right?

5. Don’t force the process: conscious deliberation follows a linear time scale, unconscious thinking does not; so let insights come in their own time.

6. Always promise yourself that you will take action on any decisions that you make. Your brain and mind will not likely be very cooperative if you ignore the fruits of your unconscious thinking!

“There is no such thing as a logical method of having new ideas…. Every great discovery contains an irrational element of creative intuition.” –Sir Karl Popper (Austrian-born British Philosopher, 1902-1994)