A Shrine to Bobby

For people interested in the late Bobby Fischer, an enthusiast has put together every public video featuring or about Fischer.

A real labor of love, and there are many fascinating items there.

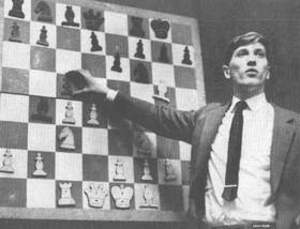

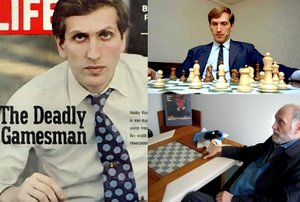

Bobby Fischer R.I.P.

News services round the world have been reporting the untimely death of Bobby Fischer, a.k.a. Robert James Fischer, the American-born chess genius.

Fischer’s match with Boris Spassky in 1972 had a huge influence on me, tempting me back to competitive chess, and over the years I studied most of his games in great detail. So I was definitely a fan.

But sadly much of the coverage has focused on some of the foul things that he said in his later years. It is particularly unfortunate because most of the reports failed to mention a number of other things about him.

I never met or examined Fischer and it is dangerous to diagnose people at long range. But there were multiple reports that made it very clear that he long ago crossed the line into mental illness.

He was always single-minded and cantankerous, and some of his allegations about cheating turned out to be correct. But when he began to believe that people could pick up or manipulate his thoughts through the fillings in his teeth, it was clear that something else was going wrong with him.

Some people have tried to link genius in chess and mental illness, but the link is at best tenuous, even though more than one very strong player has succumbed to mental illness. As we have discussed, there may be a link between creativity and schizotypal personality disorder, but the thing about chess is that high-level play requires enormous sustained concentration and motivation, to say nothing of the ability to withstand intensive mental stress. Thos are all things that become difficult as mental illness progresses.

One of the best ways of evaluating a culture is the way in which it treats its weakest members. So let us remember and celebrate Fischer’s genius and recognize that his later and ever darker life was driven by a terrible mental deterioration.

“The chessboard is the world, the pieces are the phenomena of the Universe, the rules of the game are what we call the laws of Nature. The player on the other side is hidden from us.”

–Thomas Henry Huxley (English Biologist and Educator, 1825-1895)

“Chess is the touchstone of intellect.”

–Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (German Poet, Playwright and Philosopher, 1749-1832)

Close Your Eyes and I’ll…

Every young neuroscience student learns about a classic experiment that was published in 1956 by Raul Hernandez-Peon, in which he had an electrode in the acoustic nerve of a cat, while a metronome was ticking. Every tick caused a pulse of electricity in the nerve. But as soon as the cat saw or smelled a mouse, the electrical activity plummeted: now all of his attention was on lunch, and his brain damped down the unnecessary ticking of the metronome. Something similar happens with the “Cocktail Party Phenomenon:” our ability to focus our listening attention on a single talker and ignoring other conversations that are going on.

A study by researchers from Wake Forest University Baptist Medical Center and the University of North Carolina was presented at the Society for Neuroscience conference in San Diego this week, suggesting that our brains can turn down our ability to see, so that we are better able to listen and focus on music and complex sounds.

The research used functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging in 20 non-musicians and 20 musical conductors aged 28-40, and found that both groups diverted brain activity away from visual areas during listening tasks. The activity fell in the visual regions areas as it rose in auditory ones. But during harder tasks the changes were less marked for conductors than for non-musicians.

While being scanned the subjects were asked to listen to two different musical tones played a few thousandths of a second apart and identify which was played first. The task was made harder for the professional musicians than for the non-musicians, to allow for the differences in their background.

As the task was made progressively more difficult, the non-musicians carried on diverting more and more activity away from the visual parts of the brain to the auditory, as they struggled to concentrate on the music. However, the conductors did not suppress their brains, suggesting that their years of training had given them an advantage in the way that their brains were organized and functioning. They are less likely to be distracted and are highly tuned to musical sounds.

This is like closing your eyes to listen to music and the advantage of the trained musicians is similar to the advantage that we see in the brain of the chess master compared with the amateur. Years of study and practice enable the chess player to move without much conscious thought.

It shows how well we are able to divert activity from one part of the brain to another as needed. It is that ability to be flexible and to recruit more brain when we need it that lies at the heart of the neurocognitive revolution that is changing the way that we think about the brain and mind.

Mastering Chess: Genes or Environment?

It is always interesting to look at people who have excelled at something to see what we can learn.

I recently talked about the new research indiating that there are some genes that have some impact on intelligence.

There is an interesting article in today’s New York Times, entited, “Nature? Nurture? Never Mind. Here’s a Sister Act to Watch,” by Dylan Loeb McClain. He has this to say:

“Siblings who are elite chess players are rare. The best known are probably the Polgar sisters of Hungary. Susan, the eldest, is a grandmaster and former women’s world champion. Sofia is an international master. And Judit, the youngest, is the best woman player in history.

Other notable chess-playing siblings have included the Byrne brothers, Robert, a grandmaster and the longtime columnist for The New York Times, and Donald, an international master who died at 45; and Gregory Shahade, an international master, and Jennifer Shahade, a two-time United States women’s champion, who were taught chess by their father, Michael, a master.

Why so few elite sibling players? Is it simply because it is highly unlikely for a single family to produce multiple elite players? Or do most siblings have different interests?

The questions go to the heart of a familiar debate: Is chess talent innate or nurtured?

In his popular book “The Immortal Game,” David Shenk said great chess players were made, not born, writing, “Cognitive chess research punctured the longstanding myth of the chess prodigy, the born genius.”

The best players, Shenk wrote, are the product of intensive study and training. He said the Polgar sisters, who were raised by their father, Laszlo, from an early age to be chess players, were a prime example.

Shenk recounts an episode years ago in which Susan was studying with an international master and they had a problem they could not solve. They woke up young Judit, who, half-asleep, found the solution immediately and went back to bed.

Aren’t the varying levels of talent among the Polgar sisters, who all presumably had the same training, evidence of innate differences? Possibly.

A pair of sisters who have been making a big splash lately do not seem to be separated by ability, at least so far. Nadezhda and Tatiana Kosintseva of Russia are ranked No. 14 and No. 24 in the world among women. But at the European championships, which concluded April 15, Tatiana ran away from a large field, finishing two points ahead of her sister.”

There is undobtedly some set of genes that increase the chance that someone will be good at some game or other, whether it is chess or golf. But there is also the family, school or club that can help someone to realize their true potential.

But even if the genes aren’t all there, you can still become highly competent if you have learned how to learn and if you have learned the arts of patience, perseverance and persistence.

Biology is not destiny!

Genius Genes

I have talked before about the fascinating topic of child prodigies, and the continuing debate about the contributions and interactions of nature and nurture.

There is an important new study published in the journal Behavioral Genetics that should be of interest to anyone interested in thinking, intelligence and optimizing the potential of children.

A team of researchers from Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, has gathered the most extensive evidence to date that a gene that activates signaling pathways in the brain influences at least one kind of intelligence. They have confirmed a link between the gene, CHRM2 and performance IQ, that involves a person’s ability to organize thoughts or events logically.

The team found that several variations within the CHRM2 gene could be correlated with slight differences in performance IQ scores, which measure a person’s visual-motor coordination, logical and sequential reasoning, spatial perception and abstract problem solving skills. When people had more than one positive variation in the gene, the improvements in performance IQ were cumulative.

Typical IQ tests also measure verbal skills and typically include many subtests. For this study, subjects took five verbal subtests and four performance subtests, but the genetic variations influenced only performance IQ scores.

The researchers studied DNA gathered as part of the Collaborative Study on the Genetics of Alcoholism (COGA). In this multi-center study, people who have been treated for

alcohol dependence and members of their families provide DNA samples and investigators have isolated DNA regions related to alcohol abuse and

dependence as well as a variety of other outcomes.

Some of the participants in the study also took the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised, a traditional IQ test. Members of 200 families, including more than 2,150 individuals, took the Wechsler test, and those results were matched to differences in individuals’ DNA.

By comparing individual differences embedded in DNA, the team focused on CHRM2, a muscarinic receptor gene on

chromosome 7. The CHRM2 gene activates a multitude of signaling

pathways in the brain involved in learning, memory and other higher

brain functions. The research team does not yet understand how the gene

exerts its effects on intelligence.

Intelligence was one of the first pscyhological factors that attracted the attention of people interested in the interplay of genes and environmental influences. Early studies of adopted children showed that when children grow up away from their biological parents, their IQs are more closely correlated to biological parents, with whom they share genes, than adoptive parents, with whom they share an environment.

But in spite of the association between genes and intelligence, it has been difficult to find specific variations that influence intelligence. The genes identified in the past were those that had profoundly negative effects on intelligence – genes that cause mental retardation, for example. Those that contribute to less dramatic differences have been much harder to isolate.

The St. Louis team is not the first to notice a link between intelligence and the CHRM2 gene. In 2003, a group in Minnesota looked at a single marker in the gene and noted that the variation was related to an increase in IQ. A more recent Dutch study looked at three regions of DNA along the gene and also noticed influences on intelligence. In this new study, however, researchers tested multiple genetic markers.

The lead investigator in St. Louis, Danielle Dick, had this to say,

“This is not a gene FOR intelligence, it’s a gene that’s involved in some kinds of brain processing, and specific alterations in the gene appear to influence IQ. But this single gene isn’t going to be the difference between whether a person is a genius or has below-average intelligence.”

“One way to measure performance IQ may be to ask people to order pictures correctly to tell a story. A simple example might be pictures of a child holding a vase, the vase broken to bits on the floor and the child crying. The person taking the test would have to put those pictures into an order that tells the story of how the child dropped the vase and broke it and then cried.”

“If we look at a single marker, a DNA variation might influence IQ scores between two and four points, depending on which variant a person carries. We did that all up and down the gene and found that the variations had cumulative effects, so that if one person had all of the ‘good’ variations and another all of the ‘bad’ variations, the difference in IQ might be 15 to 20 points. Unfortunately, the numbers of people at those extremes were so small that the finding isn’t statistically significant, but the point is we saw fairly substantial differences in our sample when we combined information across multiple regions of the gene.”

Most experts believe that there are at least 100 genes that could influence intelligence, but it is unlikely that any one gene is going to be the ONE determinant of how smart someone is. After all, IQ itself has very poor predictive value for anything much in life apart from achievement in high school. The many genes involved probably have small, cumulative effects on increasing or decreasing IQ, and the key will be to understand the interaction between environmental influences and these genes. We already know that childhood nutrition, socio-economic status and emotional and cognitive environments have a profound influence on intelligence and achievement. Altogether too many children have all the mental machinery but do not even realize the possibilities open to them.

It is also clear that early influences will have a lot to do with the repertoire of intelligences that a person has. In the book and CD series Healing, Meaning and Purpose I spend some time discussing Howard Gardner’s important concept of multiple intelligences. Many of us have skills in certain domains and it is a terrible mistake to assume that because a child is not very good at logical or verbal tasks, that they are not smart. After all, how many brilliant musicians, computer scientists and entrepreneurs never finished high school or college?

There is clearly more than a gene deciding our intelligence and success at certain activities. The genes may give us the machinery and the fuel, but there are clearly many other factors. I’ve always been a very keen chess player and I once had a friend who was a nationally ranked contract bridge Master. He would destroy most normal mortals at any card game: including me! Even when we played scratch games of contract bridge he would always try to avoid partnering me: he told me that I sucked too badly! 8-(

He also had a hobby: he built and designed all kinds of board games. He used to get upset that whatever the game, if it was played on a board, I almost always won. But here’s the interesting thing: our IQs were virtually identical. But he was murderously good at card games but not at anything involving a board: another refinement of intelligence. I probably did well with board games because I could plan and visualize in three dimensions. My friend had a phenomenal memory for cards that I simply don’t possess.

As the owners of some establishments in Las Vegas once discovered to their glee….

“Intelligence is quickness to apprehend as distinct from ability, which is capacity to act wisely on the thing apprehended.”

–Alfred North Whitehead (English Mathematician and Philosopher, 1861-1947)

“Intelligence is the ability to find and solve problems and create products of value in one’s own culture.”

–Howard Gardner (American Psychologist and Professor at Harvard, 1943-)

“The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas at the same time, and still retain the ability to function.”

–F. Scott Fitzgerald (American Writer, 1896-1940)

“To the dull mind all nature is leaden. To the enlightened mind the whole world sparkles and burns.”

–Ralph Waldo Emerson (American Poet and Essayist, 1803-1882)

“It is the sign of a dull mind to dwell upon the cares of the body, to prolong exercise, eating and drinking and other bodily functions. These things are best done by the way; all your attention must be given to the mind.”

–Epictetus (Phrygian-born Greek Stoic Philosopher, c.A.D.55- c.A.D.135)

A Memory for Faces

Your humble reporter has always had a good memory for faces. A month after a meeting in San Antonio at which we had about 250 attendees, he was in another part of the country when a charming man came over to say, “You won’t remember me, but I was at your lecture in Texas last month.”

He looked like a man who’d eaten a raw egg when he got the response, “Oh yes, fifth row from the back, fourth person along.”

It would be great if that memory for faces could be linked to a memory for names or something else useful. But sad to say it isn’t. Just the face, and when and where it was last seen.

But new research in neuroscience has shown us ways to tether other memories to each other.

So it was interesting to see a new report of some fascinating research from Vanderbilt University in Nashville suggesting that it is common for us to be better able to remember faces than other objects and in addition that faces “stick” the best in our short-term memory. The reason may be that our expertise in remembering faces allows us to package them better for memory, since faces are complex and their recognition is also essential for normal social relationships.

The findings are currently in press at the journal Psychonomic Bulletin and Review.

The key component of the research is visual short-term memory or VSTM has a unique way of being coded in the brain. The findings have practical implications for the way we use our memories. Clearly being able to store more faces in VSTM may be very useful in complex social situations. Just think for a moment how much most people like being remembered, particularly if you can attach a name and salient fact to the memory. Most of the successful business people and politicians that I know are remarkably adept at doing this.

Short-term memory is crucial to the way in which we create impressions and adapt to a continuously changing world. It serves as temporary storage for information that we are currently using: rather like the RAM on a computer. For example, in order to understand this sentence, your short-term memory will need to remember the words at the beginning while you read through to the end. People with some neurological and attentional problems have a real problem with doing that. VSTM is a component of short-term memory that helps us process and briefly remember images and objects, rather than words and sounds.

VSTM allows us to remember objects for a few seconds, but as with working memory and all the short-term memory stores, its capacity is limited. The new research focuses on whether we can store more faces than other objects in VSTM and the possible mechanisms underlying this advantage.

Study participants were asked to look at up to five faces on a screen for varying lengths of time (up to four seconds). A single face was later presented and the subjects had to decide if this face was part of the original display. For a comparison, the process was repeated with other objects, like watches or cars.

The researchers found that when participants studied the displays for only a brief amount of time (half a second), they could store fewer faces than objects in VSTM. They think that this is because faces are more complex than watches or cars and therefore they require more time to be encoded. Surprisingly, when participants were given more time to encode the images (four seconds), an advantage for faces over objects emerged.

The researchers believe that our past experience with learning faces explains this advantage. This theory is supported by the fact that the advantage was only observed if the faces were upright: the most familiar orientation. Faces that were shown – and therefore encoded – upside-down showed no advantage over other objects.

This is very similar to the situation in chess, where, compared with a novice, a master can instantly remember a position on the board if the pieces are in logical places. If they are arranged at random, the master does no better than the rank amateur.

Most of the textbooks tell us that the capacity of short-term memory is something is fixed, and that you either have a decent capacity or you do not. However the research indicates that you can learn to improve your capacity for this form of memory.

This makes sense: as a child your reporter rarely made notes and his parents supported him in that. More than one school teacher thought him lazy and inattentive because his note books consisted of doodles and random scribbles in between pages of homework.

How many other children have also been accused of cheating or faced punishment or ridicule simply because they had a good memory, but did not learn in the same way as the other kids?

We already have some methods for training people to get better at using visual memory, but most have been discovered by trial and error. This new research will make it that much easier to devise memory training methods rooted in brain science.

But also remember something else: sometimes forgetting is as important as remembering.

Elbert Hubbard, the American Editor, Publisher and Author who perished aboard the Lusitania in 1915, had this to say, “A retentive memory may be a good thing, but the ability to forget is the true token of greatness.”

Banquo’s Ghost

“Chess is the game which reflects most honor on human wit.” — Voltaire (a.k.a. François-Marie Arouet, French Writer and Philosopher, 1694-1778)

For anyone with even a passing interest in chess, a re-unification match for the World Championship is currently taking place in Elista, the capital city of Kalmykia, a small region of the Russian Federation that is Europe’s only Buddhist country. Though I’m sure that some would quibble about whether it should be in Europe or Asia.

The beginning of the match between two of the world’s top Grandmasters – the aggressive Bulgarian gambler Veselin Topalov and the conservative Russian, Vladimir Kramnik – has led to and 2-0 score in favor of the Russian.

So why am I mentioning this is a blog dedicated to Personal Growth, Healing and Wellness? Because the current one-sided score line has a lot to do with each of these topics. This match is not just about chess playing ability: it is also about psychological and emotional strength, character and resilience.

There was a time when chess masters were unfit, often over-weight and the majority smoked. When I first started playing in tournaments in England, it was quite normal to have ashtrays beside most of the boards.

Oh how things have changed!

Now the players prepare physically, psychologically and some even spiritually with prayer and meditation:

- Very few players smoke, not just because of long-term health risk, but because the deleterious effects of lowered oxygen levels on cognition outweigh the short-term improvement in attention caused by nicotine.

- Aerobic exercise is essential to ensure that the brain is perfused with oxygen, and if you are physically unfit you cannot expect to survive a number of games that may each last for five or six hours.

- Strength training is also essential to overall fitness and physical and the maintenance of psychological resilience. Topalov is going to need that now.

- Posture is extremely important. According to Chinese and Ayurvedic physicians and chiropractors, bad posture results in a restriction in the flow of Qi, Prana, or blood. Whether or not you believe in the flow of Qi in the body, it is easy to demonstrate that bad posture has bad effects on cognition.

- Flexibility is also an essential part of physical wellness that affects you psychologically as well as physically. Daily stretching should be part of everyone’s life.

- Relaxation and meditation: one or other or both are essential tools for maintaining your balance while under stress, and for building resilience.

- Diet: a carefully balanced nutritious diet rich in omega-3 fatty acids (without any added mercury!) and fiber is essential for optimum mental functioning.

- Fluid intake: the current recommendations are for a healthy person to drink between 80 and 120 fluid ounces of pure water each day.

- Avoid alcohol: A former World Champion – Alexander Alekhine – lost his title after turning up drunk on a number of occasions during a match to defend his title.

Looking at the pictures from the match, in both games Topalov looked intense and Kramnik far more relaxed. It could have been an illusion: I would need to be in proximity to be sure. In the first game Topalov took a needless risk in a dead level position. In the second, he had an absolutely won game. I’m no grandmaster, but even I spotted a win in three moves. How could he have failed to find it and then lost?

What is the explanation? Chess players have to play a certain number of moves in a specified time, so not only are they playing their opponent, they are also playing against the clock. The biggest prize in the game is on the line, for which both players have been preparing since childhood. And there are hundreds of thousands of people who are watching and analyzing their every move.

I know from personal experience that it can be hard enough to be interviewed on a television show being watched by millions of people, where any false statement would haunt me forever. Imagine having a battle of wits with one of the finest chess players in the world in the knowledge that every move will be analyzed for the next century, and computers are already analyzing every permutation of every move that the two players have made.

The stress on the players is unbelievable. Both have prepared for it, but it is also a matter of who has prepared best: that is a mixture of temperament and training. Just today I read an article talking about ways of avoiding stress. This is silly: stress is part of life and it can provide the motor in motivation. The trick is how we learn to respond to stress.

There is also another stressor that has only been felt by world championship contenders on two or three previous occasions. This match is being played in the shadow of the retirement of Garry Kasparov, who, in the opinion of most people, is the strongest player who ever lived, with the possible exception of Bobby Fischer. The difference is that Bobby became World Champion all by himself, with little help and by inventing a new approach to chess. It is a great tragedy that his life has apparently been blighted by mental illness, and that he has played only a few recorded games in the last 34 years.

By contrast, Garry was the strongest player in the world for twenty years, and in the opinion of most experts would probably still beat both of the current contenders. So whoever wins wants to prove himself a worthy champion. Garry’s specter remains like the ghost of Banquo in the Scottish play.

The final essential is that both players have to detach from the results of the first two games. Kramnik will obviously have his tail up now, but he is too smart and too experienced to give in to complacency. Topalov has to completely forget about the first two games and focus on what lies ahead: I’m sure that he has someone on his team working on simple techniques to stop the past from populating his psychological present.

Whatever lies ahead for these two men in the next few weeks, we shall see that chess is a microcosm of life in general.

“What is needed, rather than running away or controlling or suppressing or any other resistance, is understanding fear; that means, watch it, learn about it, come directly into contact with it. We are to learn about fear, not how to escape from it.”

–Jiddu Krishnamurti (Indian Spiritual Teacher, 1895-1986)

Child Prodigies

I’ve recently had cause to look at the published literature on child prodigies and there’s not much there. It is very surprising that such an interesting subject has been so little researched.

First a definition from a paper by David Feldman: A “prodigy was a child (typically younger than 10 years old) who is performing at the level of a highly trained adult in a very demanding field of endeavor.” There are three fields in which high-level creative results have been produced before the age of 10: Chess, Mathematics and Music. There are other fields such as art and writing in which young people may be precocious imitators. Pablo Picasso exactly mimicked his father’s drawings. There is an impressive list of child prodigies in other fields as well, but it seems that only in chess, mathematics and music have profound, original insights been contributed by preadolescent children.

There is an interesting association between mathematics and chess: many top chess players are also extremely good at mathematics. In a previous post I mentioned the English Grandmaster John Nunn, and there are many other examples. Men dominate both fields, but that does not necessarily mean that there is a natural gender difference. There’s a very interesting book entitled Breaking Through, by the chess Grandmaster Susan Polgar who was herself a prodigy, as were both of her sisters. Girls have been excluded from many of these events, or they’ve been forced to play only against girls or women. I know a young person who as a pre-teenager wanted to join the school chess club, but only went once, after discovering that all the other members were boys. A shame: she was already quite a strong player.

Both chess and mathematics involve highly developed non-verbal and visuospatial skills. The writer and critic George Steiner had this to say: “The solution of a mathematical problem, the resolution of a musical discord or conclusion of a contrapuntal development, the generation of a winning chess position can be envisaged as spatial regroupings, that have their own internal logic.” He went on to speculate, “All three fields involve enormously powerful but narrowly specialized areas of the cortex. These areas can somehow be triggered into life in a very young child and can develop in isolation form the rest of his psyche. Sexually and socially unformed, very possibly backward in every general respect, the child virtuoso or pre-teenage chess master draws on formidable but wholly localized synapses in the brain.”

In the book The Exceptional Brain, Lee Cranberg and Marty Albert suggested that these “localized synapses” lie in the right hemisphere of the brain, which is primarily involved in non-verbal visuospatial skills and pattern recognition. They also suggested that gender differences in proficiency in chess support the right hemisphere idea. But after reading Susan Polgar’s book, and spending a great deal of time analyzing the world literature on gender differences in cognition, that last point doesn’t convince me.

It is striking that three of the code breakers at Bletchley Park during the second World War, were outstanding international chess players Stuart Milner-Barry, Harry Golombek and Hugh Alexander. These code breakers who helped win the War also utilized similar skills to those needed to master a chess position or to calculate a mathematical problem.

The child prodigies seem to have some things in common:

- An unusually strong talent in a single area

- Reasonably high but not necessarily exceptionally high IQ: some people with astronomically high levels of intelligence have had problems with interpersonal adjustment, unless very carefully nurtured as children.

- Focused energy.

- Sustained effort to achieve the highest levels in their field: even chess prodigies need thousands of hours of practice, and mathematical prodigies need to work at their field.

- Unusual self-confidence.

Adults who want to improve in chess are constantly told to practice as much as possible, and to work on pattern recognition and problem solving. It is just the same in music and mathematics.

Although child prodigies may simply have better neurological equipment, usually coupled with extraordinary encouragement by their parents, I am left with a question that I posed in an earlier post. Mozart often said that when he was composing he felt as if he was taking dictation from God. That he was not the one composing, but that he was in effect picking something up from the Universe. I’ve seen countless highly gifted people tell me that their greatest insights in science, music philosophy or chess just “came to them.” The former chess World Champion Tigran Petrosian once said that he could tell when he was out of form when his calculations did not confirm the validity of his first impressions. All this implies unconscious processing to be sure, but I am not sure that it is all in the brain.

Because there is another phenomenon that has also not been much researched, and that is the phenomenon of simultaneous breakthroughs: two or more people in different parts of the world coming up with new creative solutions at the same time and without any personal contact. I shall have more to say about this in another post, but it speaks to the fundamental interconnectedness of all of us.

Maybe the child prodigies not only have special brains and special parents, but they also have access to a store of information not available to everyone.

At least not yet: We already have training methods that help people access accurate information that they did not know consciously. A story for another day.

“Genius is characterized just by the fact that it escapes classification.”

–Leopold Infeld (Polish Physicist, 1898-1968)

Intuitive Knowing and the Real Rainman

In 1988 the Dustin Hoffman won the Academy Award for Best Actor for his portrayal of Raymond Babbit in the movie Rainman.

The character was actually inspired by a real person named Kim Peek. Now in his mid-fifties, Kim has memorized more than 11,000 books, and can read a page of any book in about ten seconds. It has recently been discovered that each of his eyes can read a separate page simultaneously, absorbing every word. He can also do instant calculations on things related to the calendar and several other very specialized topics.

He and his brain has been studied in great detail by a Dr. Darold Treffert at University of Wisconsin Medical School. It is quite different from the rest of the population. He does not have the great bridge – the corpus callosum – that connects the two hemispheres in most people. Instead he just has one solid hemisphere. The right cerebellum is in several pieces. None of this really explains his abilities, though perhaps having no corpus callosum means that the right side of his brain is freed from dominance by the left. Darold Treffert makes a good point when ha says that Kim’s father is partly responsible for his brilliance: his belief in his son and his unconditional love for him may have more to do with bringing forth his remarkable skills than the wiring of his brain.

There have been many other cases of savants who had remarkable and seemingly effortless abilities. For years now I’ve collected reports about some of them. Srinivasa Ramanujan who complied over 3000 mathematical theorems in less than four years. Vito Magniamele who at the age of 10 could compute almost instantly the square root of any large number. Then there was a six-year-old child named Benjamin Blythe, who while out walking with his father in 1826, asked, “What time is it?” After being told, he gave – accurately – the exact number of seconds that he had been alive, including the two leap years. In one of his books, Oliver Sachs, describes a pair of twins in a psychiatric hospital who are said to have below “normal” intelligence, but who amuse themselves by swapping enormous prime numbers. Even the English chess grandmaster John Nunn reported how, as a child, he could do instant calculations in his head. And, at the age of fifteen, he became the youngest undergraduate at Oxford University in 300 years. Most strong chess masters will "know" where to put the pieces, but then come up with the logical reasons later on.

These abilities: to read and memorize, to do instant calculations and to have instant deep knowledge of topics is remarkably interesting and important for all of us. If complex mathematics can be done by people who have no training or intellectual sophistication, what other gifts and talents may we have lying undiscovered within us?

These observations lead to the questions; first, can anyone do the same feats as Kim Peek? Second, where does instant mathematical information come from? Third, can anyone access it? And fourth, is this similar to the way that shamans and Babylonian mathematicians obtained their information?

In Healing, Meaning and Purpose we learn that there is powerful evidence to suggest that we do have access to a whole seam of knowledge about the world around us. The anthropologist Jeremy Narby studied shamans in the Amazonian rainforest who have found safe and effective herbal treatments among the 80,000 plants available to them. They are usually used in combinations, and to have tested all the plants and all the possible combinations would have taken hundreds of thousands of years. So it cannot have been done by trial and error. I have seen something similar in traditional Chinese herbal medicine, where combinations are invariably used, and once again, if the effective ones had been discovered by trial and error, it would have taken armies of physicians working for countless thousands of years.

I don’t expect everyone to be able to become lightning calculators. Neither would most us want to be. But there are a number of ways of getting much better at tapping this intuitive knowing. It is important to tap your intuition and to use it as the ally of your reasoning.

- Relaxation, meditation or prayer are all excellent for starting the process. Meditation to explore your inner nature may take hours a day for many years, but when we use it to improve our inner knowing, a few minutes a day is all that you need. Just long enough slightly to alter your state of consciousness

- Visualize a place that you really like that you can return to at will. I learned this trick from a shaman, and it’s immensely useful. You might remember, visualize or create a space for yourself. For instance you might like to imagine going to a beach that you like.

- Ask a question: remember that the quality of your answers is dependent on the quality of your questions. So be precise and be calm when you ask you question.

- Agree with yourself that you will take action on what you learn. And that leads me to the last point for today:

- I just got an email question about how to differentiate between an impulse and an intuition. The answer to that is your response: an impulse impels you to immediate action, an intuition gives you time to reflect and to thank the Universe for what you’ve just been told.

“At every moment there is in us an infinity of perceptions, unaccompanied by awareness or reflection. That is, of alterations in the soul itself, of which we are unaware because the impressions are either too minute or too numerous.”

–Baron Gottfried Wilhelm von Leibniz (German Philosopher and Mathematician, 1646-1716)

Heroes and Villains

“Nothing is as infectious as example.”

–François Duc de la Rochefoucauld (French Writer and Moralist, 1613-1680)

I was just expecting to learn something about what’s been going on in the world today, when I came across this excellent blog item by Chess Grandmaster Susan Polgar.

Just have a look at this extraordinary video.

What amazed me just as much as the video, was that one of the commentators on Susan’s blog defended the action of the adult, on the grounds that the assaulted child had played a foul, saying, "As a parent, how easy would you find it to stand by if that happened to your kid?"

The answer to that should be, "Very easy indeed."

Adults are supposed to have some modicum of self-control.

Adults also have a responsibility to model good behavior, not just for their own children, but for all other children as well.

It reminded me of the quotation:

"If you can’t be a good example, then you’ll just have to be a horrible warning."

–Catherine Aird (a.k.a. Kinn Hamilton McIntosh, English Writer and Creator of “Inspector Sloan”, 1930-)

I’ve been involved in competitive games for most of my life, and of course they can inflame emotions. But it is how we act on those emotions that matters. I used to have an excellent chess coach named Craig Jones. He has done a lot for scholastic chess, and I remember being horrified by the antics of some parents at chess tournaments. Those scenes from the movie Searching for Bobby Fischer are not an exaggeration.

Being a victim of your emotions is bad enough. Being a lousy role model is the worst kind of irresponsibility.

I actually prefer another term to "role models." I call them heroes. And the opposite of a hero is, I suppose, a villain.

“Young people need models, not critics…”

–John Wooden (American Basketball Coach, 1910-_