Overcoming Adversity

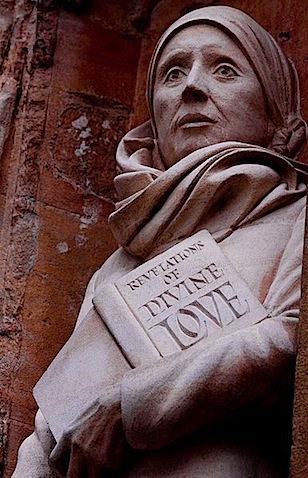

“He said not, “thou shalt not be troubled, thou shalt not be travailed, thou shalt not be diseased;” but He said, “Thou shalt not be overcome.”

–Julian of Norwich (English Mystic and Anchoress, 1342-c.1416)

Mastering Chess: Genes or Environment?

It is always interesting to look at people who have excelled at something to see what we can learn.

I recently talked about the new research indiating that there are some genes that have some impact on intelligence.

There is an interesting article in today’s New York Times, entited, “Nature? Nurture? Never Mind. Here’s a Sister Act to Watch,” by Dylan Loeb McClain. He has this to say:

“Siblings who are elite chess players are rare. The best known are probably the Polgar sisters of Hungary. Susan, the eldest, is a grandmaster and former women’s world champion. Sofia is an international master. And Judit, the youngest, is the best woman player in history.

Other notable chess-playing siblings have included the Byrne brothers, Robert, a grandmaster and the longtime columnist for The New York Times, and Donald, an international master who died at 45; and Gregory Shahade, an international master, and Jennifer Shahade, a two-time United States women’s champion, who were taught chess by their father, Michael, a master.

Why so few elite sibling players? Is it simply because it is highly unlikely for a single family to produce multiple elite players? Or do most siblings have different interests?

The questions go to the heart of a familiar debate: Is chess talent innate or nurtured?

In his popular book “The Immortal Game,” David Shenk said great chess players were made, not born, writing, “Cognitive chess research punctured the longstanding myth of the chess prodigy, the born genius.”

The best players, Shenk wrote, are the product of intensive study and training. He said the Polgar sisters, who were raised by their father, Laszlo, from an early age to be chess players, were a prime example.

Shenk recounts an episode years ago in which Susan was studying with an international master and they had a problem they could not solve. They woke up young Judit, who, half-asleep, found the solution immediately and went back to bed.

Aren’t the varying levels of talent among the Polgar sisters, who all presumably had the same training, evidence of innate differences? Possibly.

A pair of sisters who have been making a big splash lately do not seem to be separated by ability, at least so far. Nadezhda and Tatiana Kosintseva of Russia are ranked No. 14 and No. 24 in the world among women. But at the European championships, which concluded April 15, Tatiana ran away from a large field, finishing two points ahead of her sister.”

There is undobtedly some set of genes that increase the chance that someone will be good at some game or other, whether it is chess or golf. But there is also the family, school or club that can help someone to realize their true potential.

But even if the genes aren’t all there, you can still become highly competent if you have learned how to learn and if you have learned the arts of patience, perseverance and persistence.

Biology is not destiny!

Creativity and Resilience

“No great thing is created suddenly, any more than a bunch of grapes or a fig. If you tell me that you desire a fig, I answer you that there must be time. Let it first blossom, then bear fruit, then ripen.”

–Epictetus (Phrygian-born Greek Stoic Philosopher, c.A.D.55- c.A.D.135)

I have written several articles about resilience, and I have begun to talk about some of the methods for developing psychological resilience and also some of the potential consequences of not developing this essential psychological strength.

I’d also like to share with you another aspect of resilience: it is essential ingredient of creativity and of innovation.

I’ve had a longstanding fascination with the creative process, and one of the most robust findings in the research on extraordinary creative achievement is that even the greatest performers in their fields seem to produce the same ratio of undistinguished works to notable ones through their careers. The great chess player wins more often than the average one, but only sometimes produces a truly great creation. Even the best engineers and scientists conduct many unsuccessful experiments. The stories are legion of artists who produce many paintings and works of music that never win recognition and may not even be much good. Many great actors, directors, cricketers and companies have a great many failures behind – and sometimes in front – of them.

Amongst the many attributes of the high achiever in each of these fields is a remarkable ability to bounce back, to detach from the apparent failure, to see it as an education, and to understand the importance of persistence and perseverance. To take a risk, to take a step back and to learn and adapt if at first it doesn’t succeed. This never means repeating the same strategies over and over again, it means being smart and not being fazed by failure

“Unless you are willing to try, fail miserable, and try again, success won’t happen.”

–Phillip Adams (Australian Broadcaster, Filmmaker, Archaeologist and Satirist, 1939-)

I was once working with a company that had just tried to launch a promising new medicine. The initial effort had been a flop and at the time that I became involved, the company had just fired the entire marketing team. Neither the company nor the recently departed team had had the chance to find out what had gone wrong and how to build something new and different. The new team had to start from scratch and, living in constant fear, was burning out at an astonishing rate. The real problem was the inflexibility of the company that was stifling creative solutions to problems. Once that was fixed, things began to improve very quickly.

If anyone ever says that they and the company never accepts failure, it is laudable but impractical.

It’s different if an enterprise fails because people are not pulling their weight; or failing to meet deadlines; or being overly rigid in interpreting rules or just goofing off. But if everyone is trying to help, learning, and being dynamic and flexible, then it’s best not to send them on their way, but instead to see how we can learn from a failure.

And the key for you personally and the key for your company is to learn to develop personal and corporate resilience. Then creative answers have the chance to start flowing.

“Results! Why, man, I have gotten a lot of results. I know several thousand things that won’t work.”

–Thomas Alva Edison (American Inventor, 1847-1931)

“No one succeeds without effort…. Those who succeed owe their success to their perseverance.”

–Ramana Maharshi (Indian Hindu Mystic and Spiritual Teacher, 1879-1950)

Keeping Your New Year’s Resolutions

As always happens at this time of year, millions of people have made resolutions to make major changes in their lives, and magazines and websites are full of sage advice about achieving and maintaining change. Yet we all know how many of these resolution will end in failure.

But this year could be different. There is an interesting article which has been widely reported in the United Kingdom.

Jonny Wilkinson is a 26-year old rugby legend, who is prodigiously talented, but whose career has been plagued by injuries. He is known for his enormous determination and dedication to the sport, and so he became the subject of a study carried out by Professor Caroline Douglas, a sports psychologist at Loughborough University. The study was funded by the Boots, a well-known pharmaceutical and pharmacy chain, as part of the company’s Change One Thing scheme which provides starter packs to people determined to improve their lifestyles by giving up smoking, getting fit or losing weight.

We all know that there is a monumental difference between setting a goal and actually working to achieve it. I have worked with countless people who have felt that setting a goal was an achievement, rather than it being the first step in an action plan. Professor Douglas points out that sports professional place equal emphasis on the goal and the means of achievement. She and her team have come up with a formula for willpower which is:

(Goal + Action Plan + Initiation) x (Belief + Perseverance)

I think that most of us would agree that these are indeed some indispensable factors in achieving an aim, but I think that there is more to it, and that there are some better ways of staying with a program.

We must first consider motivation. There is a great deal of research about this powerful force in our lives. One of the most difficult aspects of some mental illnesses, like depression and schizophrenia, is that people can lose all their motivation. Once you have seen that happen to someone, you will never again take it for granted. Every motive that we have is driven by a need and by a desire to satisfy it. But motivation is richer and more interesting than a simple stimulus (need)/response model. It is closely linked to mood, self-regulation and context. Jonny Wilkinson is clearly motivated by a desire to play professional rugby again. But we then have to ask why? Is it pride, or money, or a need to be respected? I don’t know in his individual case, but it is essential for you to drill down as far as you can to discover what needs motivate you; what core constructs are driving you. Because if your plan or resolution is not synchronized with that core construct, or core desire, you have little hope of succeeding with a plan. The reward that you garner for successfully completing a plan must be tied to the need for action.

And here is a useful trick. You want to find two core desires that are driving you: one for yourself, and one for somebody that you care about. So giving up smoking could be driven by a desire to live longer and to be able to participate in a favorite activity, and also because you do not want your children to grow up without a parent. And here is the other part of the trick, whenever you are picking out motivating factors, look at them from physical, psychological, social, subtle and spiritual perspectives. To say that you are going to quit smoking, without taking into account the fact that you may suffer some physical withdrawal symptoms would make you plan very difficult. Our rugby player is very sensitive to the demands of his body and some of the psychological components of his will to carry on playing. But he will do better still if the other three components of his life are also being addressed.

When people are suggesting a course of action, they sometimes neglect the role of time. We are pulled to behave by our conceptions of the future, our recollections of the past and the pressures of our current situation. The importance of the past as a motivating factor has been discussed for over 60 years. There seems little doubt that your memories have a key role in planning your future. This is why techniques that help us reframe our past lives are often so helpful. I particularly advocate re-writing your life story.

Many of us do not take account of the fact that few of us exist as one integrated person. Our personalities are a composite fashioned by our genes, our environment – particularly during our formative years – our beliefs, desires, attitudes and our culture. We change, grow and mature over time, but we are also constantly buffeted by immediate changes in our environment. In very practical ways, you are not the same now as you were yesterday. Our motives will likely also change from day to day and throughout life. This is why I place so much emphasis on personal integration, so that you are able to unite and utilize all your skills to achieve whatever it. If you are integrated, you are also less likely to deviate from a course of action. I have written a lot about achieving integration in my book Healing, Meaning and Purpose, and in my forthcoming book, Sacred Cycles.

But for now, a practical consequence of this changeability is that you must start your new plan immediately, before anything else can distract you. Also start with baby steps. To say that from tomorrow you are going to exercise for an hour a day and start meditating for an hour a day will never work. I always start people with ten minutes of physical exercise, and a one minute (yes, that’s right, 60 second) meditation.

I have mentioned the value of having personal reasons for doing something, and also a reason to do something for someone else. Now there is the last piece: also see if you can work out a transpersonal reason for doing something. We have rock solid evidence that one of the most powerful motivators is a belief in something larger than yourself. People will do the most incredible things for their faith. If you can also find a third reason for following through on your New Year’s resolutions, you may well find the most powerful motivation of all.

Good luck!

Technorati tags: resolutions, Perseverance, 2006 goals, personal growth, Self Improvement