You Are What You Think and Do

It’s not too original to say that your thoughts and actions have dramatic effects on your life, but medicine had largely forgotten about the link until the 1950s. I was looking to create a pithy sentence to summarize the interaction. But I could dono better than this one, from almost two thousand years ago.

“This body, full of faults, has yet one great quality: Whatever it encounters in this temporal life depends upon one’s actions.”

–Siddha Nagarjuna (Indian Philosopher and Founder of the Mahayana School of Buddhism, c.A.D.150-c.A.D.250)

The Mind Builds the Body

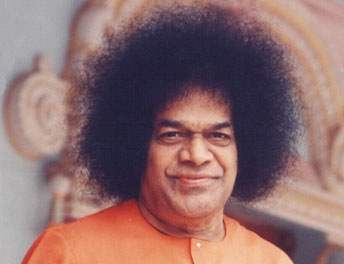

“It is the mind that builds up the body strong and shiny or wastes it to skin and bone. Mind has to be developed to savor the good and the godly, not for money and material gains.”

–Sathya Sai Baba (Indian Spiritual Teacher, c.1926-2011)

Mind and Body

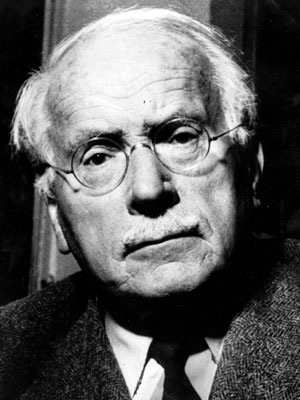

“A wrong functioning of the psyche can do much to injure the body, just as conversely a bodily illness can affect the psyche; for psyche and body are not separate entities, but one and the same life.”

–Carl G. Jung (Swiss Psychologist and Psychiatrist, 1875-1961)

“On the Psychology of the Unconscious” pp.194 Two Essays on Analytical Psychology. Collected Works 7

“Two Essays on Analytical Psychology (Collected Works of C.G. Jung Vol.7)” (C. G. Jung)

Successful Aging

One of the most promising changes in psychology is the ever-greater emphasis on what makes us healthy, rather than constantly looking at the things that make us sick. There is an important approach called Behavioral Activation (BA) Theory, which emphasizes environmental and behavioral factors as determinants of our overall well-being. According to the theory, reduced engagement in pleasurable activities may be an important precursor of reduced well-being. This makes good sense: it is estimated that as much as 90% of our higher cortical functions are designed for social interactions.

This is something that I wrote in Healing, Meaning and Purpose:

“Nothing in the Universe exists in isolation: We live in a Universe of relationships. It is inconceivable that anything can exist except in relationship to something else. The entire Universe is made up of integrated systems that function, develop and evolve together. A failure to construct and maintain healthy relationships can be a cause of much distress.

Several years ago I reported some interesting observations. At the time, I was doing a lot of research on diseases of blood vessels. I had developed a laboratory method for taking some of the cells that line blood vessels from volunteers and then growing them in a cell culture dish. We discovered that if we did not have enough cells in the dish, they would all die of “loneliness.” The exception is cancer cells, which in culture will grow on their own, like weeds.”

As an example in a paper published in February in the Archives of General Psychiatry it was shown that lonely individuals may be twice as likely to develop the type of dementia linked to Alzheimer’s disease in late life as those who are not lonely. The theory has been shown to predict psychiatric well-being in a number of populations, including the caregivers of people with Alzheimer’s disease, people with chronic pain, cancer patients and community-dwelling older people.

It is also known that psychiatric well-being, particularly emotional well-being, may play an important role in cardiovascular health. This may be due to an increase in the activity of the sympathetic nervous system that increases not only blood pressure, but also the levels of inflammatory mediators and coagulant factors in the blood.

In research from the University of California at La Jolla that was presented on Monday at the 2007 Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association in San Diego, California, twenty two people with a mean age of 70 were studied, to see if there was a link between their behavioral activation, i.e. how satisfied they were with their leisure activities, their affective well-being and their blood pressure.

The findings were as expected: the less satisfied and engaged people were, the higher was their blood pressure.

This is only preliminary data, but it confirms something that we have said before: as we get older it is as important to stay socially engaged as it is to do mental exercise.

And if you known someone who is older and isolated, you might want to go and see them.

“The most terrible poverty is loneliness and the feeling of being unloved.”

–Mother Teresa of Calcutta (Albanian-born Indian Nun, Humanitarian and, in 1979, Winner of the Nobel Peace Prize, 1910-1997)

“What makes loneliness an anguish is not that I have no one to share my burden, but this: I have only my own burden to bear.”

–Dag Hammarskjöld (Swedish Statesman, Secretary-General of the United Nations from 1953-1961, and, in 1961, Winner of the Nobel Peace Prize, 1905-1961)

Self-hypnosis and Hay Fever

I first learned to do hypnosis in 1980, and I have always found it a useful adjunctive treatment for some people, though in recent years I have spent far more tie teaching people to use self-hypnosis.

The research data on hypnosis has also been growing, to the extent that nearly two years ago an article in the Mayo Clinic Proceedings, a fairly conservative journal, suggested that the time had come for an expanded role for hypnosis in general medicine as well as a study of different techniques that are in use.

Hypnosis and self-hypnosis may affect an illness directly, or it might reduce a trigger to the illness, say if anxiety triggers an asthma attack, we could use hypnotherapy to treat the anxiety. Hypnosis may improve a person’s subjective responses to the illness. It might also be useful to help counteract side effects in people who just have to be treated with conventional medications.

Many case reports of apparent cures with hypnosis have found their way into the popular press. I have mentioned that over a period of five years I spent one to two days a week going through and checking most of these reports in all the languages that I can read. Sadly some of them turned out not to hold much water.

But now the quality of the research has improved enormously. I have been particularly impressed with some of the studies on allergy: it is very remrakable to think that we can make specific suggestions that produce demonstrable effects on the immune system. I particularly liked a study from Switzerland that was published in the journal Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics.

A team from Basel University taught 66 people with hay fever how to do self-hypnosis and found that it helped them to alleviate symptoms such as runny nose.

The volunteers also took their regular hay fever medicines, but the effect of hypnosis appeared to be additive so that they could reduce the doses that they needed to take.

The study took place over two years and included two hay fever seasons. During the first year, one group of the volunteers with hay fever were taught and asked to regularly practice hypnosis as well as take their usual allergy medicine. The training consisted of one two-hour session with an experienced trainer. The remaining volunteers had no other treatment apart from their normal allergy medication.

After a year, the researchers found the volunteers who had been using self-hypnosis had reported fewer symptoms related to hay-fever than their fellow volunteers.

During the second year, the researchers taught the remaining "untrained" volunteers how to use hypnosis. By the end of this year, these volunteers also reported improvement in their hay-fever symptoms.

Although the improvement in symptoms was not statistically significant the researchers also found that the volunteers had cut down on the amount of hay fever medication they used after learning self-hypnosis.

There is another interesting piece of research on this topic. You will probably have experienced a histamine reaction: the typical wheal, flare and swelling that can occur after, say, an insect bite. Researchers form Denmark used hypnosis to induce emotions of sadness, anger, and happiness, to see whether these emotions would have any effect on the skin’s response to histamine. Not only did mood have an effect on the skin reactions, but also people who were more susceptible to hypnosis were more reactive to histamine.

Hypnosis is being used with many clinical conditions, from asthma to migraine and irritable bowel syndrome. It is not a panacea, but it can be a very useful tool. And it tells us a lot about the power of the mind to influence virtually every system of the body.

Alexithymia

There is an important psychological symptom that can cause a great deal of distress, particularly in relationships. It is called alexithymia.

The Harvard psychiatrist Peter Sifneos originally coined the term in 1972 to describe people who had extreme difficulty in emotional cognition. The word “alexithymia” literally means “no words for mood.” People with this problem lacked the ability to understanding, processing or describing their feelings verbally. As a result, most people who have the problem are largely unaware of their own feelings or what they signify. As a result they only rarely talk about their emotions or their emotional preferences, and they are largely unable to use their feelings or imagination to focus and fuel their drives and motivations.

People with alexithymia seem unable to fantasize and many report multiple somatic symptoms. However, alexithymia is also associated with a number of other complaints, such as hypertension, irritable bowel syndrome, substance use disorders, and some anxiety disorders. Their speech is often concrete, mundane and closely tied to external events. So they will describe physical symptoms rather than emotions, and don’t understand that their bodily sensations are signals of emotional distress.

Alexithymia lies on spectrum: regular readers will remember some of our discussions about categorical and dimensional diagnoses. For some people it is little more than an inability to get in touch with their emotions. But at the other end of the spectrum are a number of illnesses in which alexithymia may occur, including schizoid personality disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, anorexia nervosa or Asperger’s syndrome. It is also much more common in victims of trauma.

Much has been written about alexithymia: a literature search earlier today generated over 8,500 publications.

It is still not clear what causes alexithymia. But this much is clear: in some people, there is a strong inborn predisposition to developing it, while in others it can develop in response to life events such as being raised in a low socioeconomic group with little social stimulation, trauma or chronic stress. For this reason we often talk about primary and secondary alexithymia.

Some neuropsychological studies have indicated that alexithymia may be due to a disturbance to the right hemisphere of the brain, which usually plays a predominant role in processing emotions. Other studies show evidence that there may be a deficit in the transmission of information between the hemispheres of the brain, with emotional information from the right hemisphere not being properly transferred to the language regions in the left hemisphere. Other studies have suggested that alexithymia may be related to a dysfunction of the anterior cingulate cortex a region of the brain involved in the control of attention, empathy, emotion and the anticipation of rewards.

Alexithymia can have some serious consequences. Apart from making relationships very difficult, it is more common in people who have near-fatal asthma attacks or have poor diabetic control. People with a history of alcohol abuse who have alexithymia are more likely to relapse. Alexithymia may predispose people to developing the insulin resistance syndrome.

As you can see, alexithymia can be dangerous: we have to have words for our feelings, or the feelings will express themselves though our bodies. It can predispose us to just about every stress-related illness, and even some illnesses that we don’t normally think of as stress-related. Since alexithymia is all about an ability to express emotions, it can be thought of as a social or informational disease. If we cannot inform others about our wants and needs, and if our minds cannot send us signals to say that something is going wrong, there could be a catastrophe lying in wait for us.

People with extreme forms of alexithymia can be very difficult to help using conventional medicine.

However, many people have minor degrees of alexithymia, and these can be helped by therapies designed to help them express emotions:

- First is to become aware of the problem: I’ve had good success with asking people to keep an emotions “log book:” if they are having odd symptoms, how good are they about having appropriate emotions? I ask them to keep a note of their emotions in response to normal interactions with other people, or while watching television or a movie. If the person feels nothing while watching something really emotional, that can help him or her see that there is a problem. Simply learning to be more expressive can help mild cases: there are an array of forms of psychotherapy that can help.

- In mild cases, we have had some good results with flower essences. There’s not a shred of scientific proof that they help, but clinically they often do. The same goes for two other helpful approaches:

- Homeopathy: there are over a dozen remedies that may help

- Tapping therapies