Reflecting On Reactions

“Any time you react negatively to a person or to anything you must understand that this is your own unfinished business. Do you hear that?”

–-Elisabeth Kübler-Ross (Swiss-born American Psychologist, 1926-2004)

“The Cocoon & the Butterfly (Kbler-Ross in Person)” (M.D., Elisabeth Kbler-Ross)

Separating the Psyche and the Brain

“We must completely give up the idea of the psyche’s being somehow connected with the brain.”

–Carl G. Jung (Swiss Psychologist and Psychiatrist, 1875-1961)

New Paths in Psychology

“Anyone who wants to know the human psyche will learn next to nothing from experimental psychology. He would be better advised to put away his scholar’s gown, bid farewell to his study, and wander with human heart through the world.

There, in the horrors of prisons, lunatic asylums and hospitals, in drab suburban pubs, in brothels and gambling-hells, in the salons of the elegant, the Stock Exchanges, Socialist meetings, churches, revivalist gatherings and ecstatic sects, through love and hate, through the experience of passion in every form in his own body, he would reap richer stores of knowledge than textbooks a foot thick could give him, and he will know how to doctor the sick with real knowledge of the human soul.”

–Carl G. Jung (Swiss Psychologist and Psychiatrist, 1875-1961)

“New Paths in Psychology” In: Two Essays on Analytical Psychology. P.409 Collected Works 7

“Two Essays on Analytical Psychology (Collected Works of C.G. Jung Vol.7)” (C. G. Jung)

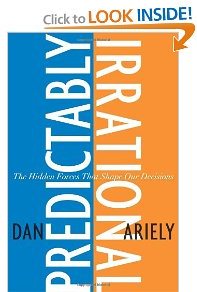

The Price of a Placebo

Placebos can be powerful things, whether they come wrapped in a nicely colored box, or take the form of an enthusiastic clinician.

Dan Ariely, a behavioral economist at Duke University, and author of the excellent new book Predictably Irrational has written a letter in this week’s issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association in which he suggests that pill costing ten cents is not as effective at preventing pain as a $2.50 pill, even when they are identical placebos.

Ariely and a team of collaborators at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology recruited 82 people to participate in a study in which light electric shocks were administered to participants’ wrists to measure their subjective rating of pain. The 82 study subjects were tested before getting the placebo and after. Half the participants were given a brochure describing the pill as a newly approved painkiller that cost $2.50 per dose. The other half was given a brochure describing it as marked down to 10 cents, without saying why.

- In the full-price group, 85 percent of subjects experienced a reduction in pain after taking the placebo.

- In the low-price group, 61 percent said the pain was less.

Although simple and small, the experiment raises some large questions.

As Dr. Ariely says,

“Physicians want to think it’s the medicine and not their enthusiasm about a particular drug that makes a drug more therapeutically effective, but now we really have to worry about the nuances of interaction between patients and physicians.”

The results are consistent with previous data about how people perceive quality and how they anticipate therapeutic effects. What is interesting here is the combination of the price-sensitive consumer expectation with the placebo effect of being told that a pill works.

Would it help if prescription medications offer cues from packaging, rather than coming in indistinguishable brown bottles?

Is there a way of giving people cheaper or generic medications without them thinking they will not work?

As Dr Ariely says,

“At the very least, doctors should be able to use their enthusiasm for a medication as part of the therapy. They have a huge potential to use these quality cues to be more effective.”

Wise words!

“It requires a great deal of faith for a man to be cured by his own placebos.”

–John L. McClenahan (American Physician and Writer, 1935-)

“Your thoughts are like the seeds you plant in your garden. Your beliefs are like the soil in which you plant these seeds.”

–Louise Hay (American Spiritual Teacher, 1927-)

“Change your beliefs and you change your destiny.”

–Sterling Welling Sill (Elder of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, 1903-1994)

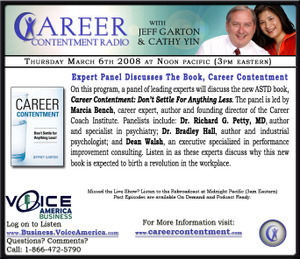

Career Contentment

I am very happy to report that my friend Jeff Garton’s new book – Career Contentment: Don’t Settle for Anything Less – has just come out.

As you will see from my review, I just love the book, and it is amazing how Jeff’s work and mine fit together.

We are going to be having a panel discussion about the book on www.Business.VoiceAmerica.com on Thursday March 6th at 3PM Eastern, which is noon Pacific time. The discussion is also going to be archived for people in other time zones. I plan to put up a link as soon as it is available.

There is a nice press release here.

I hope that you can listen in: I think that you will get a lot of food for thought!

“Contentment is natural wealth, luxury is artificial poverty.”

-Socrates (Greek Philosopher, 469-388 B.C.E.)

Fatalism and Ethics

We are constantly inundated by reports of the consequences of bad decision-making, and that leads us to consider two issues: genetic determinism – the notion that our behavior is totally the result of our genes – and whether or not we have free will. This is a hugely important issue, not only for each of us personally, but also for our views about morality and the justice system. And what happens when everyone becomes convinced that they have no free will and that “they’re genes made them do it?”

We know from our own experience as well as empirical studies that changing a person’s sense of responsibility can change his or her behavior.

Interestingly, the link between fatalistic beliefs and unethical behavior seems never to been examined scientifically.

In two recent experiments published in the journal Psychological Science psychologists Kathleen Vohs of the University of Minnesota and Jonathan Schooler of the University of British Columbia decided to see if otherwise honest people would cheat and lie if their beliefs in free will were manipulated.

They gave college students a mathematics exam. The math problems appeared on a computer screen, and the subjects were told that a computer glitch would cause the answers to appear on the screen as well. They were told that to prevent the answers from appearing, the students had to hit the space bar as soon as the problems appeared.

This was a ruse: the researchers were observing to see if the participants surreptitiously used the answers instead of solving the problems honestly on their own. Before the test they used a well-established method to prime the subjects’ beliefs regarding free will. Some of the students were told that science has disproven the notion of free will and that the illusion of free will was an artifact of brain activity. The other group where told nothing about free will.

The results were clear: those with weaker convictions about their power to control their own destiny were more likely to cheat when given the opportunity compared with those whose beliefs about controlling their own lives were left untouched.

The researchers then went a step further to see if they could get people to cheat with unmistakable intention and effort. The experimenters set up a different deception. This time they had the subjects take a very difficult cognitive test. Then they were asked to solve a series of problems without supervision and to score themselves. They also “rewarded” themselves $1 for each correct answer. To collect the cash they had to walk across the room and help themselves to money in a manila envelope.

The psychologists had previously primed the participants to have their beliefs in free will bolstered or reduced by having them read statements supporting a deterministic view of human behavior.

This study shows that those with a stronger belief in their own free will were less likely to steal money than were those with a weakened belief.

The results of this study indicate a significant value in believing that free will exists. The work also raises some significant questions about personal beliefs and personal behavior.

“The flame of Christian ethics is still our highest guide.”

–Sir Winston Churchill (English Statesman, British Prime Minister, 1940-1945 and 1951-1955, and, in 1953, Winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature, 1874-1965)

“You’re born with intelligence, but not with ethics.”

–Masad Ayoob (American Firearms and Self-defense Instructor and the Director of the Lethal Force Institute in Concord, New Hampshire, 1948-)

“Fatalism, whose solving word in all crises of behavior is “All striving is vain,” will never reign supreme, for the impulse to take life strivingly is indestructible in the race. Moral creeds which speak to that impulse will be widely successful in spite of inconsistency, vagueness, and shadowy determination of expectancy. Man needs a rule for his will, and will invent one if one be not given him.”

–William James (American Psychologist and Philosopher, 1842-1910)

“To live lightheartedly but not recklessly; to be gay without being boisterous; to be courageous without being bold; to show trust and cheerful resignation without fatalism -this is the art of living.”

Jean de La Fontaine

“Custom has furnished the only basis which ethics have ever had.”

–Joseph Wood Krutch (American Naturalist, Writer and Critic, 1893-1970)

Talking with Your Hands

In recent years there has been a small but growing literature that seems to support an idea going back to Roman times: certain specific movements may facilitate learning and a number of positive mental states.

Now, according to research from the University of Chicago that is reported in this month’s issue of Journal of Experimental Psychology: General gesturing can help children to learn new and correct mathematical problem-solving strategies. And the learning sticks: if they are taught new material later, children taught to gesture are more likely to succeed on math problems.

The investigators conducted two studies of 176 children in late third and early fourth grade, all of whom had been making mistakes in solving math problems. The children were randomly assigned the students to three groups:

- Told to gesture

- Told not to gesture

- Not told to do either

In the studies’ baseline phase, students had to solve six age appropriate math problems on a chalkboard and explain to an experimenter how they solved each one. The researchers coded the children’s videotaped efforts, analyzing gestures and utterances that conveyed problem-solving strategies.

Compared with the children who were not told to do anything, those who were told to move their hands when explaining how they had solved a problem were four times as likely to manually express correct new ways to solve problems. They still did not give the right answer, but their gestures revealed an implicit knowledge of mathematical ideas. As one example, if the problem needed for the sides to be equal, children might sweep their palm first under a problem’s left side and then under its right side. So they had implicit knowledge. Their problem was in turning explicit knowledge into correct answers. The second study showed that gesturing prepared them to benefit from subsequent instruction. Children told to gesture solved 1.5 times more problems correctly compared with the children who had been told not to gesture.

The authors conclude,

“Telling children to gesture encourages them to convey previously unexpressed, implicit ideas, which in turn makes them receptive to instruction that leads to learning.”

Gesturing appears to help children to produce new problem-solving strategies, which in turn gets them ready to learn. The authors speculate that gesturing may help kids notice aspects of the math problems that may be more easily grasped through gestural representation

The findings extend previous research that body movement not only helps people to express things they may not be able to verbally articulate, but actually to think better. At the same time, gesturing offers a potentially powerful new way to augment the teaching of math. Strategies for math problems have focused on externalizing working memory, such as writing things down in certain ways. However, children often find it hard to recall and use those strategies. Gesturing may be more accessible, and help break through the roadblock.

This makes sense: we are hardwired to learn motor actions. That was an important skill long before the first person learned the basics of arithmetic. It is quite well known in educational circles that when it comes to learning, “doing” is 2-3 times more efficient than “listening.” But even “doing” is nowhere near as good as questioning, being questioned and then teaching.

(The entire article is available for free download here.)

“He who wishes to teach us a truth should not tell it to us, but simply suggest it with a brief gesture, a gesture which starts an ideal trajectory in the air along which we glide until we find ourselves at the feet of the new.”

–José Ortega y Gasset (Spanish Philosopher, 1883-1956)

Height and Quality of Life

It’s difficult to guess it from that mug shot over on the left, but your humble reporter is six foot four, or, for our more metrically inclined friends, 193 centimeters. Believe it or not, on my mother’s side of the family, that would have made me one of the shortest. Over the years I have heard all the arguments about boys getting their height form their mothers, height being correlated with various maladies, and the old chestnut about tall people being more successful. Something that clearly escaped Alexander the Great, Napoleon Bonaparte and Adolph Hitler.

Nonetheless, some interesting correlations between height and psychological measures have begun to emerge in recent years.

Regular readers may recall the work from the West of England that has found some association between growth hormone and intelligence.

A new study in the journal Clinical Endocrinology indicates that your height in adult life significantly affects your quality of life, with shorter people reporting worse physical and mental health than people of “average” height. Shorter people judge their state of health to be significantly lower than their “normal” height peers do. I put quotes around words like “average” and “normal, since they have particular scientific rather than personal connotations.

The data for this study came from 14,416 people enrolled in the 2003 Health Survey for England, carried out by the UK Department of Health. In this survey, participants filled out a health-related quality of life (HRQoL) questionnaire and a nurse measured their height. A person’s health-related quality of life refers to their perceived physical and mental health over time rather than a measure of his or her actual health.

People in the shortest height category (men shorter than 162 cm {5 foot four inches} and women shorter than 151 cm {4foot eleven inches}) reported they experience significantly lower HRQoL than people of “normal” height. The effect size is more pronounced the shorter a person is. This means that a small increase in height has a much larger positive effect on a short person than it does on a person of “normal” height.

One of the reasons for doing this study, which was supported by Novo Nordisk, is that there are some uncommon problems such as growth hormone deficiency or Turner syndrome in which people have short stature. The argument is that if their height causes psychological distress, there is a greater justification for treatment with growth hormone, which can increase their final adult height by approximately 4-10 cm (1.5 to 4 inches) depending on the underlying cause.

There is also another point. Some people already have a shorter stature, and most are perfectly well adapted. But it is important to be aware that some may be suffering in silence, and it is so important to ensure that they get the help that they need.

We cannot cure everything problem in the world, but we should be able to treat anything.

New Treatment Options: Knowing What to Use

One of the main reasons that I created this blog is that I want to empower you: I want to give to give you the information that you need to care for yourself and the people around you.

One of the problems with many new treatments is that they promise the earth, sometimes drag people away from things that may help them and then fail to deliver.

This is something that I struggled with in the field of holistic medicine for thirty years. I constantly hear and see fantastic claims that cannot be right and are often based on a complete misunderstanding of how the body functions. On the other hand there are some highly unorthodox methods and techniques that can be amazingly helpful. My job has been to find out which is which!

But it is not only in the field of unorthodox medicine. I have recently heard about something very questionable in the field of psychotherapy. Somebody has invented a new form of therapy that cuts across and ignores decades of research. He is now offering certifications in his method. So long as you have a very basic healthcare qualification, you pay him a few hundred dollars, do an online training and then you can set up shop as a therapist. Many members of the public do not know how little regulation there is for some of these therapies.

Here are some guidelines for checking out a new therapy or remedy:

1. Efficacy

Be suspicious of any treatment or therapist if they:

- Claim that a treatment works for everyone: I have yet to find ANY treatment that works for everyone

- Only use case histories or testimonials as proof. The plural of anecdote id not evidence. If we see or hear about something that looks promising, it is essential to confirm the reports with systematic, independent controlled research. Be aware that if that has not been done, the person selling you the treatment or the therapist claiming to help is essentially experimenting on you. And if they want to experiment they need your consent and the approval of an Institutional Review Board. And don’t buy into the “my work is so brilliant and cutting edge that nobody will publish it in a journal.” It is hard to publish really new work, but we cannot believe what people are saying until it has been subjected to peer review: other experts go through the work with a fine toothcomb to see if it is right.

- Cite only one study as proof. Hundreds of promising studies have turned out to be dead ends when someone else tried to repeat it. You can be a lot more confident if several studies have shown the same thing.

- Cites a study that did not have a control (comparison) group. That is always a first step in evaluating a new treatment.

- Cite a study that you cannot see yourself. We spend a lot of time checking some of the claims made on infomercials and websites. They often talk about some obscure study in a hard-to-find journal written in a foreign language. We go and find the papers and if necessary translate them. We constantly find that the studies quoted contain results that are 180 degrees away from what they claim.

- Only reference themselves. This recently came to light with a form of therapy that comes with a short book. There was not one scientific citation, but loads of self-references, so it looked as if there was something credible behind it.

- Testing a treatment without a control group is a necessary first step in investigating a new treatment, but subsequent studies with appropriate control groups are needed to clearly establish the effectiveness of the intervention.

2. Safety?

Be wary if:

- A therapist or someone promoting a remedy cannot tell you the exact consequences of not following up with some other treatment. Safety is not only about the safety of a product or a therapy: it is also about the risks of declining a proven treatment

- A therapist tells you stop any other treatment that you are on without discussing the risks of stopping it, and without discussing the situation with any previous therapist. It does not matter whether you were on a medication or having acupuncture. Different treatments interact, and stopping and starting can be risky. If a therapist who does not prescribe medications tells you stop them, be very, very careful. There are precise ways to discontinue most treatments

- A remedy comes without precise directions about how to use it

- Something does not list its contents or ingredients

- A product has no information or warnings about side effects

- If a product or therapeutic approach is described as natural, with the implication that natural means safe. Hurricanes, arsenic and deadly nightshade are all natural!

3. Promotion

Be very cautious if a therapy or treatment:

- Claims to be based on a secret formula or a secret that has been deliberately hidden from you

- Claims that the particular treatment or therapy is being suppressed or unfairly attacked by the medical or therapeutic communities

- Claims to work immediately and permanently for everyone

- Is described as an “Amazing breakthrough” or a “Miracle.”

- Claims to be a cure for something that other experts believe is incurable. They could be right, but then we have to go back to the first point about efficacy

- Is only promoted through infomercials, self-promoting books, online or by mail order

4. Evaluating Media Reports

- When evaluating reports of health care options, consider the following questions:

- What is the source of the information? Good sources of information include medical schools, government agencies (such as the National Institutes of Health and the National Institute of Mental Health), professional medical associations, and national disorder/disease-specific organizations. Information from studies in reputable, peer-reviewed medical journals is more credible than popular media reports.

- Who is the authority? The affiliations and relevant credentials of “experts” should be provided, though initials behind a name do not always mean that the person is an authority. Reputable medical journals now require researchers to reveal possible conflicts of interest, such as when a researcher conducting a study also owns a company marketing the treatment being studied or has any other potential conflict of interest.

- Who funded the research? It may be important to also know who funded a particular research project.

- Is the finding preliminary or confirmed? Unfortunately, a preliminary finding is often reported in the media as a “breakthrough” result. An “interesting preliminary finding” is a more realistic appraisal of what often appears in headlines as an “exciting new breakthrough.” You should track results over time and seek out the original source, such as a professional scientific publication, to get a fuller understanding of the research findings

5. What Are the Financial Implications of This New Therapy or Remedy?

- Is the treatment covered by health insurance?

- What out-of-pocket financial obligation will you or your family have?

- How long will this out-of-pocket financial obligation be?

- Is there any kind of guarantee?

Tips for Finding Reliable Information Online

The good news is that the Internet is becoming an excellent source of medical information. The bad news is that with its low cost and global entry, the Web is also home to a great deal of unreliable health information.

In addition to the tips cited earlier, Web surfing really needs some special considerations:

Know the source. The domain name tells you the source of information on the Web site, and the last part of the domain name tells you about the source. For example:

.edu = university/educational

.biz/.com = company/commercial

.org = non-profit organization

.gov = government agency

The same rules do not always apply if you are looking at websites in other countries.

Obtain a “second opinion” regarding information on the Web. Pick a key phrase or name and run it through a search engine to find other discussions of the topic or talk to your health care professional.

Experts who spend time and trouble evaluating reports and then publish their findings online will often answer questions. RichardGPettyMD.blogs.com is one that does, and there are many others.

Counterfactual Thinking

Most of us have experienced the “I should have,” “I could have,” “If only I” and “I would have” moments. Times when we lament our missteps. We say to ourselves that we should have invested in a certain stock, should have married Agnes or become a doctor instead of a cab driver. Though it can be positive, for some people this kind of thinking becomes so pervasive that they simply cannot take any action in the present. So anything that we can learn about this process will likely help a great many people.

We refer to this process in which we evaluate how we would do things differently, as “counterfactual thinking.” Though it can be positive, and help us learn from our mistakes, it is a common psychological mechanism that causes us to harbor feelings of disappointment and regret. For some people this kind of thinking becomes so pervasive that they simply cannot take any action in the present. So anything that we can learn about this process will likely help a great many people.

A common research strategy in the study counterfactual thinking, is to have people read stories in which the main character makes decisions that will ultimately doom him or her to failure. Researchers then ask them how they would have done things differently.

But this method may not provide a complete picture of this mental process. New research published in the June issue of Psychological Science, which is a journal of the Association for Psychological Science, shows that our counterfactual thinking may be markedly different when we are actually experiencing failure rather than reading about someone else’s.

In a series of experiments, Vittorio Girotto of the University luav di Venezia in Venice, Italy and his colleagues attempted to demonstrate and explain the differences in counterfactual thinking between actors who actually experienced the problem and readers who just read about it.

The experimental subjects were divided into two groups:

- Actors who were asked to participate in a game in which they could win a reward by solving a math problem. They were then asked to choose one of two sealed envelopes: One was said to contain a difficult problem, and one supposedly contained an easy problem. In reality, both envelopes contained a problem that was nearly impossible to solve in the allotted time. Once the actors failed, they were asked to write at least one way in which things would have been better for them.

- In the second group, “Readers” read a story with a protagonist who faced the same choice and ended with the same negative outcome as the subjects did in the actor condition. Like the actors, readers were required to write at least one way in which things would have been better for the protagonist.

The readers and actors were very different in their counterfactual thinking. Readers tended to undo the protagonist’s choice to tackle the problem, while actors changed the way in which they tried to solve the problem. So a reader would say, “I should have picked another envelop,” while the actor would ask if he could use a calculator.

These results run counter to previous theories of counterfactual thinking. It was assumed that people who read a story construct the same counterfactuals as people who experienced the events described in the story. It was also believed that actors tend to avoid self-blame at all costs when thinking of alternatives. Instead, the actor-reader differences emerged even in conditions in which actors’ decisions made the best decisions that they could. The researchers said,

“Actors and readers produce different counterfactuals because they rely on different information, not because they have different motivations.”

In both cases, “what might have been” thinking can be stressful.

This research confirms something that we have been teaching for years:

Learn to detach from your aims and desires: you need passion and purpose. But you do not need the third “P:” Pain

Liberate yourself from the past: Healing, Meaning and Purpose has a whole section on novel ways to get rid of some of the “stuff” that most of us carry around in our bodies, our minds and our subtle systems.