Patience on the Path

“Be patient. The path of self-discipline that leads to God-realization is not an easy path: obstacles and sufferings are on the path; the latter you must bear, and the former overcome — all by His help. His help comes only through concentration. Repetition of God’s name helps concentration.”

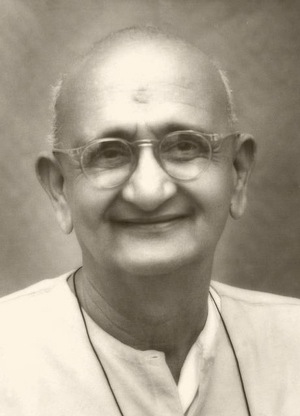

–Swami Ramdas (a.k.a. Papa Ramdas, Indian Spiritual Teacher, 1884-1963)

Time and Patience

“The strongest of all warriors are these two: Time and Patience.”

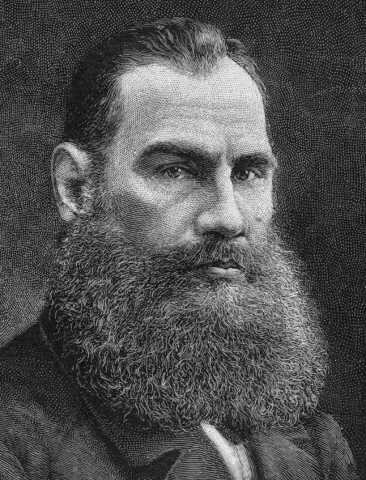

–Count Leo Tolstoy (Russian Writer and Philosopher, 1828-1910)

Learning By Example

“Perfect health, sincerity, honesty, straightforwardness, courage, disinterestedness, unselfishness, patience, endurance, perseverance, peace, calm, self control are all things that are taught infinitely better by example than by beautiful speeches.”

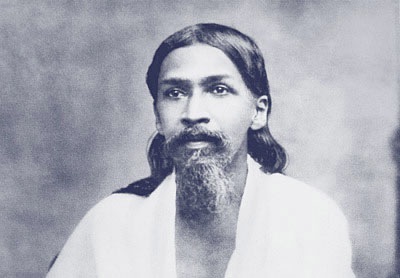

–Sri Aurobindo (a.k.a. Aurobindo Ghose, Indian Nationalist Leader, Mystic, Philosopher and Creator of Purna (Integral) Yoga, 1872-1950)

Mastering Chess: Genes or Environment?

It is always interesting to look at people who have excelled at something to see what we can learn.

I recently talked about the new research indiating that there are some genes that have some impact on intelligence.

There is an interesting article in today’s New York Times, entited, “Nature? Nurture? Never Mind. Here’s a Sister Act to Watch,” by Dylan Loeb McClain. He has this to say:

“Siblings who are elite chess players are rare. The best known are probably the Polgar sisters of Hungary. Susan, the eldest, is a grandmaster and former women’s world champion. Sofia is an international master. And Judit, the youngest, is the best woman player in history.

Other notable chess-playing siblings have included the Byrne brothers, Robert, a grandmaster and the longtime columnist for The New York Times, and Donald, an international master who died at 45; and Gregory Shahade, an international master, and Jennifer Shahade, a two-time United States women’s champion, who were taught chess by their father, Michael, a master.

Why so few elite sibling players? Is it simply because it is highly unlikely for a single family to produce multiple elite players? Or do most siblings have different interests?

The questions go to the heart of a familiar debate: Is chess talent innate or nurtured?

In his popular book “The Immortal Game,” David Shenk said great chess players were made, not born, writing, “Cognitive chess research punctured the longstanding myth of the chess prodigy, the born genius.”

The best players, Shenk wrote, are the product of intensive study and training. He said the Polgar sisters, who were raised by their father, Laszlo, from an early age to be chess players, were a prime example.

Shenk recounts an episode years ago in which Susan was studying with an international master and they had a problem they could not solve. They woke up young Judit, who, half-asleep, found the solution immediately and went back to bed.

Aren’t the varying levels of talent among the Polgar sisters, who all presumably had the same training, evidence of innate differences? Possibly.

A pair of sisters who have been making a big splash lately do not seem to be separated by ability, at least so far. Nadezhda and Tatiana Kosintseva of Russia are ranked No. 14 and No. 24 in the world among women. But at the European championships, which concluded April 15, Tatiana ran away from a large field, finishing two points ahead of her sister.”

There is undobtedly some set of genes that increase the chance that someone will be good at some game or other, whether it is chess or golf. But there is also the family, school or club that can help someone to realize their true potential.

But even if the genes aren’t all there, you can still become highly competent if you have learned how to learn and if you have learned the arts of patience, perseverance and persistence.

Biology is not destiny!

Airport Security and That Liquid Explosive

Well, your humble reporter was in New York on Thursday and became a statistic: one of the people held up for hours after the arrests in the United Kingdom and Pakistan. I mused that it was not aiport security that foiled the plot, but some very good detective work.

I’m not usually the most patient of people, but I grew up in Europe during the years that multiple groups of terrorists considered us to be fair game, so I’m used to this kind of thing. On 9/11/01, I happened to be lecturing in New Jersey, got trapped after the airline system was closed down, and ultimately took one of the very first commercial flights in the country once the airports were re-opened.

It was not machismo, but an understanding that if we give in to terror, we have lost. Turned out to be a good thing that I was on the flight: three people had panic attacks outside the departure gate, and some of the tapping therapies did them the world of good.

As I spent hours waiting, my thoughts turned to one of my first loves: chemistry. I had some terrific teachers who taught me to really understand science.

Since several had been in the military, we used to have all kinds of discussions about how to make things go bang. An unusual way to learn chemistry. But now I had several hours to see what I could remember: I began to wonder what explosives these could have been?

From the little described in the media, I came up with a short list. A few minutes ago I saw an article on the Scientific American website that seems to have come up with many of the same thoughts that I did. The one that I had not thought of was Astrolite.

This whole thing is such a sad development, but it just shows the importance of understanding some of the roots of our current global crisis and what we may each be able to do help.

More on Chess and the Mind

After my last article about some of the things that one can learn from chess, a blogger in Australia added “patience” to my list. And he is quite right. Except that I have, sad to say, never mastered the art of patience. It’s a character flaw. Maybe I would have had more success at the Royal Game if I had been just a bit more patient. I suppose a few extra IQ points might have helped too…

There is a nice article on Susan Polgar’s blog : Susan is the oldest of three remarkable Hungarian sisters who were trained to be geniuses from early childhood by their father László Polgár. She now lives in New York, and she is an International Chess Grandmaster who also happens to be fluent in seven languages. She is doing a great deal to promote the enormous benefits of chess, particularly in the United States. Clearly the sisters had “good genes,” but it is inspiring to see what can be done for youngsters if they are exposed to a highly enriched environment early in life. But there is something else to the Polgar story. Despite the stereotype that over-education might lead people to be unbalanced eggheads, all three have turned out to be remarkably normal and charming young women with children of their own. One sister – Judit – is the highest rated female chess player of all time, and the third sister – Sofia – is an International Master living in Israel.

The normalcy of the sisters is in stark contrast to the situation of many children that I have seen in Japan, who are already having extra tuition in Kindergarten. Scholastic failure is a recognized cause of suicide in Japan, and the Japanese actually have a word for death from overwork: Karoshi.

I wish Susan well in her efforts to promote chess, but I would also love her to share with the world how she and her sisters managed the balancing act of marrying extreme intellectual development with normal emotional and interpersonal relationships. That is in many ways even more remarkable than the sisters’ extraordinary accomplishments.

Technorati tags: chess, balance, Susan Polgar,