From Empathy to Enlightenment

“Let thy Soul lend its ear to every cry of pain like as the lotus bares its heart to drink the morning sun.

Let not the fierce Sun dry one tear of pain before thyself hast wiped it from the sufferer’s eye.

But let each burning human tear drop on thy heart and there remain, nor ever brush it off, until the pain that caused it is removed.

These tears, O thou of heart most merciful, these are the streams that irrigate the fields of charity immortal.”

–Helena Petrovna Blavatsky (Russian Author, Translator and Founder of the Theosophical Society, 1831-1891)

“The Voice of the Silence (Verbatim Edition)” (Helena Petrovna Blavatsky)

Empathy and Compassion

“Let thy Soul lend its ear to every cry of pain like as the lotus bares its heart to drink the morning sun.

Let not the fierce Sun dry one tear of pain before thyself hast wiped it from the sufferer’s eye.

But let each burning human tear drop on thy heart and there remain, nor ever brush it off, until the pain that caused it is removed.

These tears, O thou of heart most merciful, these are the streams that irrigate the fields of charity immortal.”

–Helena Petrovna Blavatsky (Russian Author, Translator and Founder of the Theosophical Society, 1831-1891)

“The Voice of the Silence (Verbatim Edition)” (Helena Petrovna Blavatsky)

What We Most Need to Change

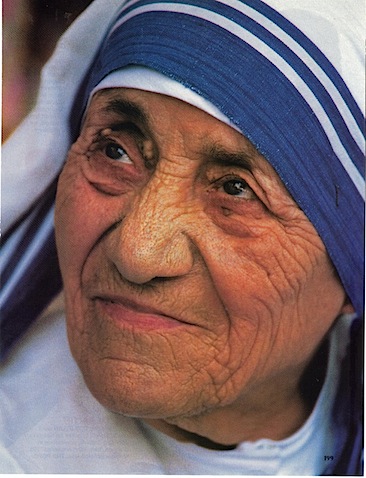

“I have come to realize more and more that the greatest disease and the greatest suffering is to be unwanted, unloved, uncared for, to be shunned by everybody, to be just nobody to no one.”

–Mother Teresa of Calcutta (Albanian-born Indian Nun, Humanitarian and, in 1979, Winner of the Nobel Peace Prize, 1910-1997)

“My Life for the Poor: Mother Teresa of Calcutta” (Ballantine Books)

Empathy and Understanding

“It is easier to know and understand men in general than one man in particular.”

–François, Duc de La Rochefoucauld (French Writer and Moralist, 1613-1680)

Men, Women and Forgiveness

We recently discussed the importance of forgiveness on health. Over the years studies have shown that men tend to be more vengeful than women, presumably because they have been taught from childhood to empathize with others and build relationships. Though there could yet be a biological basis for this difference.

New data from Case Western Reserve University, Florida State University, Arizona State and Hope College published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology suggests that forgiveness does not come naturally for both sexes. Psychologist Julie Juola Exline’s research indicates that men have a harder time forgiving than women do. However that can change if men develop empathy toward an offender by seeing they may also be capable of similar actions. That empathy closes the gender gap and men become less vengeful.

The authors conducted seven forgiveness-related studies (1,2,3,4,5,6,7) between 1998 and 2005 that involved more than1,400 college students: Gender differences have been a robust finding.

The studies used hypothetical situations, actual recalled offenses, individual and group situations and surveys to study the ability to forgive. When men were asked to recall offenses they had committed themselves, they became less vengeful toward people who had offended them. Women started at a lower baseline for vengeance, but thinking about their own transgressions had no effect on levels of unforgiving. When women were asked to recall a similar offense in relation to the other’s offense, women felt guilty and tended to magnify the other’s offense.

The researchers found that people of both genders are more forgiving when they see themselves as capable of committing a similar action; it tends to make the offense seem smaller and increases empathic understanding of the offense. Therefore people similar to the offenders and therefore more forgiving attitudes.

The ability to identify with the offender and forgive also happens in intergroup conflicts. In a study on forgiveness of the 9/11 terrorists Exline comments that,

“When people could envision their own government committing acts similar to those of the terrorists, they were less vengeful. For example, they were less likely to believe that perpetrators should be killed on the spot or given the death penalty, and they were more supportive of negotiations and economic aid.”

It is not difficult to see that prosecution and defense attorneys are going to study this data carefully. It will likely come into play during jury selection processes.

And I am going to think about it the next time that I am called upon to serve on a medical school interview board.

“An eye for an eye will only serve to make the whole world blind.”

–Mahatma Gandhi (Indian Nationalist and World Teacher, 1869-1948)

“And be ye kind one to another, tenderhearted, forgiving one another, even as God, for Christ’s sake, hath forgiven you.”

–The Bible (Ephesians 4:32)

“Everyone and everything I see will lean toward me and bless me. I will recognize in everyone my dearest friend. What could there be to fear in a world that I have forgiven, that has forgiven me?”

–A Course in Miracles (Book of Spiritual Principles Scribed by Dr. Helen Schucman between 1965 and 1975, and First Published in 1976)

The Seat of the Emotions and the Gateway to Reason

“If passion drives, let reason hold the reins.”

–Benjamin Franklin (American Author, Inventor and Diplomat, 1706-1790)

For many centuries reason and emotion have usually been held to be two poles of a magnet, the North and South of the psyche. Every now and then someone has proposed some other psychological lodestone, but most have finally devolved into this simple binary model.

Yet a moment’s introspection shows us that reason and emotion are inextricably linked. We know from people with alexithymia and a dizzying array of “personality disorders,” that a real-life Mr. Spock would be a hobbled creature. Yet we also know that simple binary models of pleasure and pain as the drivers or behavior are over simplified. It appears that one of the great attainments of many mammalian species – and who knows how many others – is an ability to be moved by more complex considerations of loyalty, propriety and even morality.

There is an important study in this month’s issue of the Journal of Neuroscience. The amygdala is a central processing station in the brain for emotions and is involved in laying down emotional memories. A shock or extreme pleasure may both leave their traces in the amygdala, so it plays a key role in survival.

But this new research shows that the amygdala also plays a role in working memory, a higher cognitive function that is critical for reasoning and problem solving. If you ask someone for a telephone number and you instantly dial the number and then forget it, that is working memory in action. If you choose to remember the number for later, it moves out of working memory into longer term memory stores. In some senses working “memory” is a little bit of a misnomer: it is a function that enables us to manipulate information extremely rapidly.

In two different functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies with a total of 74 participants, individual differences in amygdala activity predicted behavioral performance on a working memory task. The experimental subjects were asked to look either at words, such as rooster, elbow, and steel, or faces of attractive men and women. Then they were asked to indicate whether or not the current word or image matched the one they saw three frames earlier. Try it for yourself, and you will see that this is quite challenging. The subjects’ brains were scanned while completing the tasks.

People with stronger amygdala responses during the working memory task also had faster response times.

This is exceptionally important for anyone interested in thinking and learning: it shows that a region of the brain thought to be involved primarily, or perhaps even exclusively, in processing emotions is also involved in higher cognition, even when there is no emotional content.

I think it most likely that the amygdala may be involved in vigilance, perhaps preparing people to better cope with challenging situations and also improving their ability to sort information according to its relevance to the current situation. This is something that people with poor resilience find hard to do, so it may be that the amygdala is involved in developing and maintaining resilience.

This study helps to prove the total inter-relatedness of emotion and cognition and supports learning strategies that are based upon integrating emotion with facts. One of the ways in which health care students are able to remember enormous numbers of facts is by attaching them to patients with whom they have worked. Emotion, interest and empathy can dramatically accelerate learning.

Lassie and the Shepherd

On the same day that I read some research purporting to show that dogs aren’t much good at sounding the alarm if a human is in trouble, I also read about a Scottish shepherd who collapsed after having a stroke while herding his flock. His two sheepdogs, Border Collies – surely the smartest dogs in the world – kept him warm overnight as he lay in a field. The following morning he was found by helicopter rescuers after one of the dogs ran around trying to catch their attention.

The research ended by saying that Lassie would probably have left Jimmy in the well.

But I’m not so sure. When I’m not traveling, I’m around animals all day long. They all have their personalities: they have their favorite other animals, their favorite – and least favorite – humans, as well as a clear sense of propriety. If one of the clan gets attention, then they all expect equal amounts of talking to, petting and generally being made a fuss over. They are all very good barometers of the character of the people whom they meet.

Some people come to the house and the dog and the cats are all over them like a nasty rash. With others they keep their distance or avoid them altogether.

If they like you they will do anything for you in their own feline, canine or equine ways. If you are not on their most favored humans list, they probably wouldn’t cross the road to spit on you if you were on fire.

I don’t see any evidence in the research that the dogs’ subjective feelings were taken into account.

It’s a safe bet that the Scottish shepherd loved those dogs like his own children and they probably reciprocated. You have to fabricate some really creative explanations as to why two dogs would stay out in the perishing cold with their human when they could have just taken off and found themselves a warm place for the night.

And as for my comment about the intelligence of Border Collies? You may have heard the jokes about how many dogs it takes to change a light bulb:

Golden Retriever:

The sun is shining, the day is young, we’ve got our whole lives ahead of us, and you’re inside worrying about a stupid burned out bulb?

Poodle: I’ll just blow in the Border Collie’s ear and he’ll do it. By the time he finishes rewiring the house, my nails will be dry.

Border Collie: Just me. And while I’m here I’ll make sure that your entire wiring is up to code.

Your Mind and Your Brain Know the Difference Between the Real and the Imagined

I have just seen a psychologist do a spot on television where, in the middle of some otherwise great advice, she repeated a well-known piece of nonsense: “Your brain can’t tell the difference between organizing your closets and organizing to prepare for a disaster.” This notion that the brain and the mind react the same way to real and imagined events has launched hundreds of self-help programs, but is dead wrong.

We have loads of evidence that the brain is extremely good at telling the difference between an image in external space and something that you are visualizing in your mind’s eye. Your brain wouldn’t be much good to you if it couldn’t tell the difference between an imagined event and the real thing!

Here’s just one example from many. I’ve written about empathy before: a crucial attribute for healthy functioning. There has been a debate going on for many years now: how can you put yourself into some one else’s shoes? Does it somehow involve merging our own view of the world with someone else’s? A new study sheds important light on this topic.

When you are empathizing with someone you can imagine how they perceive a situation and the feelings that they experience as a result. When you imagine someone else’s pain, is it the same as imagining pain on oneself? Many of us become quite emotional when we hear about something sad, but is the genesis of the emotion the same as it would be if something sad is happening to us? These experiments used functional magnetic resonance and participants were shown pictures of people with their hands or feet in painful or non-painful situations and instructed to imagine and rate the level of pain perceived from different perspectives. These results show that imagining someone else’s discomfort or one’s own, activated different regions in the brain. People did not somehow merge themselves with their image of the other person.

That makes good sense: we need to be able to keep ourselves separate from other people, until we have gained a high degree of internal control. I have known dozens of empaths and psychics who have been damaged by being unable to separate another person’s experiences form their own. Many have come to see me as patients, because they were experiencing the distress of others around them. They were helped not by medication, but by energetic work and training in how to control their gifts.

“All persons are a puzzle until at last we find in some word or act the key to the man, to the woman; straightaway all their past words and actions lie in light before us.”

–Ralph Waldo Emerson (American Poet and Essayist, Known as America’s Teacher, 1803-1882)

Technorati tags: Imagination Empathy Brain Psychic