Non-pharmacological and Lifestyle Approaches to Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: 2. Nutritional Supplements

It sometimes surprises people to learn that the FDA does not currently regulate the production of supplements and herbal products. Therefore their purity and contents may vary considerably. Though most of them are fine, there have been endless examples of supplements that contained no active ingredients or were adulterated with heavy metals or prescription medicines.

Amino Acid Supplementation

The idea of using amino acid supplementation is based on reports of low levels of amino acids in ADHD, including the particular amino acids – tyrosine, phenylalanine and tryptophan – that are the building blocks of catecholamines and serotonin.

Several open and controlled studies in both adults and children have reported a short-term benefit from tryptophan (precursor of serotonin), tyrosine (precursor of catecholamines), or phenylalanine (precursor of catecholamines) and S-adenosyl-methionine supplementation.

However, no lasting benefit beyond 2–3 months has been demonstrated: both children and adults develop tolerance. Even short term, there is a lot of dispute about whether these supplements work at all.

Vitamins

Three strategies for vitamin supplementation are:

- Recommended Daily Allowance (RDA) multivitamin preparations

- Megavitamin multiple combinations

- Megadoses of specific vitamins

The first is not controversial, although there is always a discussion about whether the RDA’s is correct. There has not been any credible research on the effects of his kind of supplementation in diagnosed ADHD even though some reports suggest mild deficiencies in diet and blood levels. There is some evidence that micro-nutrient supplementation will help the intelligence and ability to concentrate in children without ADHD, but whether the same holds in ADHD, we simply do not know.

The second strategy, megavitamin multiple combinations, has not been found effective in double-blind placebo-controlled short (2 weeks) and longer (up to 6 months) trials in ADHD and the related comorbidity of learning disorder, although it is always possible that the researchers did not use the correct mixture of vitamins and minerals.

As things stand megavitamin combinations do not seem worth pursuing for children or adults, and some may be risky.

The third strategy, the use of single vitamins in huge doses to alter neural metabolism has not been explored despite some encouraging early reports.

Minerals

Deficiencies of iron, zinc, and magnesium have been noted more commonly among children with ADHD than among normal children.

Iron

Iron is a coenzyme involved in the synthesis of catecholamines, so there has been a lot of interest in iron deficiency as a possible cause of a number of neurocognitive problems. Iron deficiency may be due to poor diet, celiac disease, excessive milk ingestion, infection, gastrointestinal losses or lead. And of course in adults, many women are chronically iron deficient. Children with ADHD may have lower iron stores and in a study of nearly 100 children, there was a significant inverse correlation between ferritin levels and scores on a standard ADHD rating scale.

Zinc

Zinc is a co-factor for 100 enzymes, many involved in neural metabolism. It is also necessary for fatty acid absorption and for the production of melatonin, the light–related hormone that helps regulate dopamine function. Zinc is so important for the normal functioning of the brain that it is plausible that deficiency would adversely affect behavior and that restoring optimal levels may provide some benefit.

Zinc has been found to be lower in some children with ADHD. In a study of 44 children with diagnosed ADHD, zinc had a significant inverse correlation with attention, even controlling for gender, age, income, and diagnostic subtype. In large randomized, controlled trial, children given zinc sulfate (150 mg/day) or placebo, the zinc-takers had significantly more improvement for impulsive behavior and socialization; the best response was observed in those children who had low zinc levels to begin with. We do not know if using mega-doses of zinc will confer any benefit.

Magnesium

Magnesium deficiency can cause a wide spectrum of neurological and psychiatric disturbances and can result from a many factors including increased requirement during childhood.

In one study, 30 out of 52 children with ADHD had low levels of magnesium in their red blood cells. An open-label study supplementing them with 100 mg daily of magnesium and viamin B6 for 3-24 weeks led to reduced symptoms of hyper-excitability (physical aggression, instability, attention to school work, muscle tension and spasms) after 1 to 6 months of treatment.

Conclusions

It is usually just enough to ensure that children with ADHD have a decent diet. But in some it may be necessary to take supplements to ensure that they are getting an adequate dietary intake of iron, zinc, and magnesium.

Other Supplements

Essential Fatty Acid Supplementation

The membranes of nerve cells are composed of phospholipids containing large amounts of polyunsaturated fatty acids, especially the n-3 and n-6 (or omega-3 and omega-6) acids. What these terms mean is simply that the first unsaturated bond is 3 or 6 carbons, respectively, from the noncarboxyl “tail” of the molecule). Humans cannot manufacture these fatty acids and hence are “essential” and needed in the diet. Essential fatty acids (EFAs) are also metabolized to prostaglandins and other eicosanoids, which modify many metabolic processes, activate eicosanoid receptors, and interact with pro-inflammatory cytokines.

Rats that have low levels of omega-3 fatty acids in their brains, tend to be hyperkinetic.

Fish oil/omega-3 fatty acids

Children with lower levels of omega-3 fatty acids seem to have significantly more behavioral problems, temper tantrums, and learning, health, and sleep problems than did those with high proportions of omega-3 fatty acids.

In a 4-month trial of 63 children with ADHD, DHA (one of the essential fatty acids found in fish oil) supplements alone had no significant impact on behavior. In a randomized, controlled trial of fatty acids supplementation for 117 children with developmental coordination disorder, there were significant improvements for children on active treatment in reading, spelling, and behavior over 3 months of treatment. But when the tratments were crossed over, similar changes were seen in the placebo group. We definitely need more research on fish oils. Most experts think that children need around 1000mg/day and adults up to 3000mg/day.

There may be a downside: large doses of fish oil may inhibit platelet aggregation and increase the risk of bleeding; its use should be discontinued 48 hours before having surgery. Many people do not like the taste of fish oil, though in capsules that is not normally a problem.

Gamma-Linolenic Acid

Evening primrose oil contains gamma linoleic acid. Two small randomized, controlled trials conducted in the 1980s showed only marginal benefits of evening primrose oil for children with ADHD.

L-Carnitine

The mixed results with essential fatty acids might have something to do with the transport and metabolism of the fatty acids. One essential component of these metabolic pathways is L-carnitine, so it too has been tried in ADHD, but so far there are no good trials to help us.

Glyconutritional Supplements

Glyconutritional supplement contains basic saccharides necessary for cell communication and the formation of glycoproteins and glycolipids.

In an open trial of glyconutritional and phytonutritional (flash freeze-dried fruits and vegetables) supplementation with 17 ADHD children, researchers found significant reductions in parent ratings of inattention, hyperactivity, impulsivity, and oppositional symptoms, with similar trends on teacher ratings. In a second open trial of the same supplements in 18 children, researchers found reductions in parent inattention ratings from 2.47 to 2.05 and hyperactivity-impulsivity ratings from 2.23 to 1.54. There was an impressive statistical value for this trial and the results were sustained for 6 weeks. However, a third open trial reportedly failed to duplicate such results. There have not been any reported trials of glyconutritional supplements in adults.

Dimethylaminoethanol

Dimethylaminoethanol (DMAE) has several accepted names, including deanol and dimethylethanolamine. It is the immediate precursor of choline (trimethylaminoethanol) and is claimed to increase production of acetylcholine. There have been several studies claiming a small effect on vigilance, alertness and mood, but there are questions about its safety.

Melatonin

Melatonin helps regulate dopamine function in the brain, so it has been a natural candidate for the treatment of ADHD. A randomized, controlled trial 25 children with ADHD and chronic insomnia were either given melatonin (5 mg) or placebo daily at 6pm; the melatonin significantly improved sleep onset, decreased sleep latency, and increased total sleep time. Although there was no significant change in ADHD behavior over the 4-week study, all the parents in the trial felt the improvements in sleep were enough to justify continuing to give it for 1 year after the study. These results have been replicated in another study: melatonin helps with sleep problems in chdlren wth ADHD, but had no efect on problem behavior, cognitive performance or quaity of life. Melatonin may be helpful for children with ADHD who have trouble with sleep.

As you can see there are a great many options, but despite all those articles in magazines and online that promise the earth, the evidence for most of the approaches is thin.

At the moment the best option that may help seems to be fish oils. Choosing the best supplement is not easy, but the one for which there is most evidence, and which seems to be the most pure and mercury-free is OmegaBrite.

A Very Helpful Website for Parents with Children at Risk of ADHD, Addiction or Anti-social Personality Disorder

Though I’ve said a hundred times that biology is not destiny, there is no question that some genes can predispose us to rect to th environment in certain ways. Some people are genetically-loaded for some specific illnesses. It is not always inevitable that the illness will emerge, and there is more and more evidence that there are strategies that can reduce the risk of many illnesses appearing.

There is a most helpful website maintained by Dr. Liane Leedom. I recently reviewed her book at Amazon.com.

The website is full of helpful advice on helping with people with children at risk for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, addiction or antisocial behavior. Liane’s interest is in parenting strategies for children who have genetic risk for these problems.

Well worth a visit.

Non-pharmacological and Lifestyle Approaches to Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: 1. Diet

You can find some articles on Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) here, and also some of the evidence that ADHD is a “real” illness and not just a label for socially unacceptable behavior. That being said, it is essential to take extra care when making the diagnosis. Mud sticks, and diagnostic mud sticks like glue. It can be hard to “unmake” a diagnosis.

As with any problem, the most effective way of helping it is to address the physical, psychological, social, subtle and spiritual aspects of the situation.

Medicines can definitely have a place in the management of ADHD, and the reason for treating ADHD is not so that people get better grades in school or do better at their jobs. It is to prevent the long term problems that may follow from inadequately treated ADHD.

There is a large and growing body of research on non-pharmacological approaches to treating ADHD. A literature search has turned up over two hundred papers, over half of which report some empirical research. Some of the research is summarized in a short paper aimed at health care professionals.

Research has shown that more than 50% of American families who receive care for ADHD in specialty clinics also use complementary or alternative medical (CAM) therapies, if you include things like modifying their diet or other aspects of their lifestyle. Despite that, only about 12% of families report their use of CAM to their clinician. Despite that low rate of families reporting the use of unorthodox therapies, a national survey of pediatricians showed that 92% of them had been asked by parents about complementary therapies for ADHD. The trouble is that many pediatricians have not been taught very much about the pros and cons of these approaches.

The most commonly used CAM therapies for ADHD are dietary changes (76%) and dietary supplements (> 59%). I have talked about food additives and one type of diet in the past. Now let’s look in a little more detail.

The 3 main dietary therapies for ADHD are:

- The Feingold diet,

- Sugar restriction, and

- Avoiding suspected allergens.

Sometimes these diets are used in combination.

The Feingold Diet

The Feingold diet is the most well known dietary intervention for ADHD. It aims to eliminate 3 groups of synthetic food additives and 1 class of synthetic sweeteners:

Synthetic colors (petroleum-based certified FD&C and D&C colors);

Synthetic flavors;

BHA, BHT and TBHQ ; and

The artificial sweeteners Aspartame, Neotame, and Alitame.

Some artificial colorings such as titanium dioxide are allowed.

During the initial weeks of the Feingold program, foods containing salicylates (such as apples, almonds, and grapes) are removed and are later reintroduced one at a time so that the child can be tested for tolerance. Most of the problematic salicylate-rich foods are common temperate-zone fruits, as well as a few vegetables, spices, and one tree nut.

During phase 1 of the Feingold diet, foods like pears, cashews, and bananas are used instead of salicylate-containing fruits. These foods are slowly reintroduced into the diet as tolerated by the child.

The effectiveness of this diet is controversial. In an open trial from Australia, 40 out of 55 children with ADHD had significant improvements in behavior after a 6-week trial of the Feingold. 26 of the children – 47.3% – remained improved following liberalization of the diet over a period of 3-6 months.

In another study, 19 out of 26 of children responded favorably to an elimination diet. What is particularly interesting is that when the children were gradually put back on to a regular diet, all 19 of them reacted to many foods, dyes, and/or preservatives.

In yet another study, this one a double-blind, placebo-controlled food challenge in 16 children, there was a significant improvement on placebo days compared with days on which children were given possible problem foods. Children with allergies had better responses than children who had no allergies.

Despite this research many pediatricians, particularly in the United States, do not believe the evidence regarding the effectiveness of elimination diets or additive-free diets warrants this challenging therapy for most children.

There is an interesting difference in Europe. In 2004 a large randomized, blinded, cross-over trial of over 1800 three-year-old children was published. The results showed consistent, significant improvements in the children’s hyperactive behavior when they were on a diet free of benzoate-preservatives and artificial flavors. They had worsening behavior during the weeks when these items were reintroduced. On the basis of this and other studies, in 2004 schools in Wales banned foods containing additives from school lunches. It has been claimed that since the ban, there has been an improvement in the afternoon behavior of students.

The biggest problem with the Feingold and other elimination diets is that they are hard to follow and to maintain. But for some children and families, the inconvenience and stricter attention to food have worthwhile results.

It is also essential to ensure that children on any kind of diet maintain adequate nutrition: there have been many examples of that simple rule not being followed.

Sugar Restriction

The notion that sugar can make children “hyper” entered the mainstream over twenty years ago, and is now on the list of things that “everyone knows.” But happily it is not true. At least 12 double-blind studies have failed to show that sugar causes hyperactive behavior. Some researchers suggest that sugar or ingestion of high-carbohydrate “comfort foods” is actually calming, and that children who seek these foods may be attempting to “self-medicate.”

There are plenty of very good reasons for children to avoid candy, but hyperactivity is not one of them.

Food Allergies

There is clear evidence that children, and perhaps adults with ADHD are more likely to have allergies. That lead to the obvious question whether children with ADHD allergic or sensitive to certain foods. (It is useful to differentiate “allergies” that are the result of abnormal reactivity of the immune system to proteins in food, from “sensitivities” that are the direct result of substances in food: the two have different treatments.)

It is certainly true that food allergies and food sensitivities can generate a wide range of biological and behavioral effects. Gluten sensitivity (celiac disease) is known to be linked to an increased risk of ADHD and other symptoms.

In an open study of 78 children with ADHD referred to a nutrition clinic, 59 improved on a few foods trial that eliminated foods to which children are commonly sensitive. For the 19 children in this study who were able to participate in a double-blind cross-over trial of the suspected food, there was a significant effect for the provoking foods to worsen ratings of behavior and to impair psychological test performance.

For more than 30 years one of the tests used to track allergies has been the radioallergosorbent test (RAST). It is not much used these days since technology has moved on. In an allergy testing study of 43 food extracts 52% of 90 children with ADHD had an allergy to one or more of the foods tested. Over the next few years several researchers carried out open-label studies in which children with ADHD and food allergies were treated with a medicine called sodium cromoglycate, that prevents the release of inflammatory chemicals such as histamine from mast cells. Some of the reports suggested that it could help in some children.

Other popular dietary interventions include eating a low glycemic index diet to avoid large swings in blood sugar. Another strategy has been to “go organic” to reduce the burden of pesticides, hormones, antibiotics, and synthetic chemicals in the child’s system. These diets need more scientific study but they are probably safe if expensive.

There are plenty of practitioners and commercial entities who claim to be able to identify food sensitivities with all kinds of methods from blood and muscle testing to electrical and energetic techniques. Some may be helpful, but few have been proven to be effective.

What Should Parents do About Diet, Nutrition, Allergies and Sensitivities?

It is very difficult to predict whether an individual child will be helped by changes in diet. However, as long as the child’s needs for essential nutrients are met these diets should be safe.

It is an extremely good idea for parents to keep a diet diary for one to two weeks to see if anything obvious jumps out. Then trying an additive-free diet, low in sugar and avoiding foods that are suspected of exacerbating symptoms. You will normally find the answer – yes or no – within a few weeks.

What is the Evidence for Food Sensitivities and ADHD in Adults?

Not a lot!

There are plenty of people who have reported that dietary restrictions have helped them, but there is very little evidence. One of the problems about looking for food sensitivities is that there is a high placebo response rate. But if you have adult ADHD, it may be worth investigating. Just make sure that any diet that you use is nutritionally sound. And if you don’t find anything reconsider another approach.

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: Diagnosis and Complications

I have had a great many requests to talk more about attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): what it is, and what it is not; when is it a problem and when is it just “normal” childhood or adolescent behavior? And what evidence is there for non-pharmacological approaches?

Although there is a lot of information about ADHD available in books and on line, some is better than others, and some is misleading. I have recently had the privilege of giving a series of lectures on each of these topics, and many people have thought that I had a different take on the issue, so I an going to summarize some of the lectures here.

First I would like to direct you to a short article on the diagnosis on ADHD. The most important point is that we have to tell the difference between kids being kids and a problem that needs treatment.

Second is an article that talks about some of the problems that may follow if someone has ADHD and it is not diagnosed or treated.

Over the next two days I am going to follow up with articles that I have written on "Non-pharmacological and Lifestyle Approaches to Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder":

Diet, nutrition, allergies and sensitivities

Herbs and supplements

Movement, exercise, sleep and environmental design

Massage, qigong, tapping therapies and acupuncture

Mind-body approaches to treating ADHD

Homeopathy and flower essences in ADHD

Using Integrated Medicine in ADHD

“Thoughts of themselves have no substance; let them arise and pass away unheeded. Thoughts will not take form of themselves, unless they are grasped by the attention; if they are ignored, there will be no appearing and no disappearing.”

–Bhikshu Ashvaghosha (Indian Playwright and Master of Buddhist Philosophy, c. A.D. 1st Century)

“The true art of memory is the art of attention.”

–Samuel Johnson (English Biographer and Essayist, 1709-1784)

“Attention makes the genius; all learning, fancy, and science depend upon it. Newton traced back his discoveries to its unwearied employment. It builds bridges, opens new worlds, and heals diseases; without it taste is useless, and the beauties of literature are unobserved.”

–Robert Aris Willmott (English Author, 1809-1863)

A Possible New Treatment for Attention Deficit Disorder

Although I am always eager to use non-pharmacological treatments whenever possible, sometimes it just isn’t possible to us them on their own. I’ve outlined some of the reasons for treating attention deficit disorder (ADD) in a previous post.

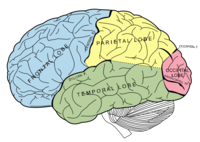

We should soon hear whether the regulatory authorities in the United States and Europe are going to approve a medicine – guanfacine – that we currently use for treating high blood pressure, for the treatment of ADD. In the United States it is currently sold under the trade name Tenex. The medicine works in the brain by modulating a population of receptors known as the central nervous system α-2 adrenergic receptors, which results in reduced sympathetic outflow leading to reduced vascular tone. Its adverse reactions include dry mouth, sedation, and constipation.

The idea of using a medicine like this for treating ADD is not new. Fifteen years ago researchers showed that receptor agonists like clonidine decreased distractibility in aged monkeys. And clonidine itself has occasionally been used for treating ADD for over twenty years.

Guanfacine seems to have some unique properties including decreasing the activity in the caudate nucleus while increasing frontal cortical activity. We would therefore expect it not only to help with ADD symptoms, but it may have some quite specific properties relating to learning new material. A key point is that if approved it will only be the second nonstimulant medicine for ADD, along with atomoxetine (Strattera). Many clinicians have had a lot of trouble with side effects of atomoxetine, particularly if it is used in adult men. So if guanfacine is approved, and if it does not have the same side effects, that would be a big bonus.

New options are always welcome, but it remains important for any new pharmacological treatment to be nested in an Integrated approach, which always includes nutrition, physical and cognitive exercises, psychological and social help, as well as attending to the subtle and spiritual aspects of the problem.

And ADD can be a very big problem, despite the protestations from people who claim that it is a non-disease dreamed up by pharmaceutical companies. Our interest is not just professional, but personal. Every single day we see what can happen if someone forgets their medicine.

If the FDA gives approval for guanfacine I shall immediately report it for you, as well as giving you details of all the safety and tolerability data.

Procrastination and Perfectionism

Regular readers will know that I am convinced that we are now in a fourth phase of the personal development movement, in which it is now incumbent on writers and speakers to support their propositions and suggestions with empirical data. And if there is no data, then they need to collect some.

There is an idea that has launched a thousand self-help books, websites and seminars: that perfectionism is the primary cause of procrastination. There was a time when I was the Prince of Procastinators. After my “recovery” I became an expert on helping others overcome the problem. So I’ve done a lot of research on procrastination. As I was preparing this posting I looked at over a dozen books and two dozen websites, and almost every one of them had “perfectionism” as a or the cause of procrastination.

But is it true?

The answer is “No.”

Professor Piers Steel from the University of Calgary Haskayne School of Business has published an important paper in the current issue of the American Psychological Association’s Psychological Bulletin.

The paper confirms some things that we have always suspected, for instance that most people’s New Year’s resolutions are doomed to failure, but demolishes the idea perfectionism is the root of procrastination.

The evidence from this work – which is the fruit of ten years of research – is that procrastinators have less confidence in themselves and a lower expectancy that they can actually complete a task. By contrast, perfectionists procrastinate less, but they worry about it more.

These are the main predictors of procrastination:

- Low levels of self-confidence

- Low expectancy of being able to complete a task

- Being task averse

- Impulsivity

- Distractibility

- Motivation to complete the task

The paper also makes the point that not all delays are procrastination: the key factor is that a person must believe that it would be better to start working on given tasks immediately, but still not start work on it.

It is said that 95% of people procrastinate at some time in their lives and 15-20% are chronic procrastinators.

Amazingly, there is a mathematical formula that predicts procrastination. Steel calls this Temporal Motivational Theory, which takes into account the key factors such as the expectancy a person has of succeeding with a given task (E), the value of completing the task (V), the desirability of the task (Utility), its immediacy or availability (Ã) and the person’s sensitivity to delay (D).

This is the magic formula: Utility = E x V/ (Ã) D

I am impressed by this work, but it is also supremely practical, because it helps point us at appropriate targets to treat our own tendency to procrastinate.

There is also something else that is very important. Many of us believe from our own experience that perfectionism is indeed the root of our own procrastination. For a long time I thought so myself. But research like his helps us to re-analyze our understanding of ourselves. We all begin by using folk psychology to explain our behavior and the behaviors of other people. The trouble is that those explanations are often wrong. Research like this can be enormously helpful as we grow and develop as individuals.

It remains unclear why some people may be more prone to procrastination, but some evidence suggests it may be genetic. It may also be more common in people with anxiety disorders or attention deficit disorder.

You may also be interested to evaluate your own tendency to procrastinate. There is a terrific resource here.

“If we wait for the moment when everything, absolutely everything is ready, we shall never begin.”

–Ivan Sergeyevich Turgenev (Russian Writer, 1818-1883)

“The wise does at once what the fool does at last.”

–Baltasar Gracián (Spanish Jesuit Philosopher and Writer, 1601-1658)

“Procrastination is opportunity’s assassin.”

–Victor Kiam (American Businessman and Former CEO of Remington, 1926-2001)

“I have spent my days stringing and unstringing my instrument, while the song I came to sing remains unsung.”

— Rabindranath Tagore

(Indian Poet, Playwright, Essayist, Painter and, in 1913, Winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature, 1861-1941)

Food Additives and Behavior

Few things generate as much heat and as little light as the debate about a possible association between food additives and cognition, mood and behavior.

There are a number of ways in which food may influence all three, including:

- Malnutrition

- Composition of the diet

- Nutrient quality of the diet

- Eating habits

- Pharmacological effects of foods

- Food allergy

- Food sensitivity

- Contamination of food with heavy metals, hormones and pesticides

- Fatty acid deficiency

- Food additives

It is often surprising to learn that many people do not realize that in children – particularly if malnourished – omitting breakfast can have a marked effect on cognitive functioning. But it is the last of those that I want to look at today.

Until the 1950s if food manufacturers wanted to add color to a food it was done primarily with natural plant and vegetable based compounds: pale red colors could be achieved from beets; green from chlorophyll-containing vegetables; yellows and orange could be achieved from extracts from a number of other plants and spices. But then things began rapidly to change as we outlined in Healing, Meaning and Purpose.

The notion that food additives could be a cause of hyperactivity is at least 30 years old. I think that Ben Feingold was the first to introduce the idea and with it his notoriously difficult diet.

Over the years there have been some positive clinical trials of the diet and some negative. But I think that every clinician working with behavior problems has seen some startling improvements in some children and adolescents when they go on an elimination diet.

In 1985 a controversial study published in the Lancet claimed to show that 79% of hyperactive children had symptomatic improvement when food chemicals were removed from their diet. Then when the food chemicals were re-introduced the symptoms returned. No other study has ever produced figures anything like that high.

It is also important that in young children, though additives may cause a problem in some, there does not seem to be a link between allergies and food sensitivities, and parents often pick up behavior changes that simple clinical screening tools do not. So mom and dad may really know best.

Several years ago we tried to look at the impact of food additive not on behavior, but on headache. When the additives were administered double blind, we were unable to replicate most people’s symptoms, even when they were sure that a certain food caused a problem.

However, unsupervised restriction diets are not without their dangers. And we also need to make sure that practitioners know what they are doing: I once saw a young woman who had seen by an “alternative allergist,” who had left her on a diet consisting of spring water, rice and lettuce. And nothing else.

Another problem is that many of us do not know what additives are lurking in the food that we eat. There was a recent study in the United Kingdom indicated that on average, Britons consume 20 different food additives every day, with some eating up to 50. Yet most people were unaware of this figure, with nearly half of the 1,006 people surveyed thinking they ate only 10 additives each day.

The research also found that many people did not understand which foods are most likely to contain additives. I have not yet seen the raw data from this study, but I shall have more to say about it once it becomes available.

A number of large independent studies are currently underway (for example, here) which should help us to better identify who is susceptible to additives, how to test for sensitivity to additives and who might benefit from their withdrawal.

The trouble with a lot of the discussion about food additives, behavior, mood and cognition is that it usually begins from a false premise: that there is a single cause for a behavior.

When I am teaching it continues to astonish me that most health care professionals still expect there to be one “cause” for a problem. Yet as I have mentioned before, this is rarely clinical reality.

A food additive may be associated with problems, but only in a minority of children, and only if they are genetically predisposed and if the right set of environmental circumstances are in place.

If you suspect a problem, first, learn to look at labels. And see if simple exclusion helps. An allergist is the next stop, but also ask whether an additive could be causing a biochemical rather than an allergic problem. If it is a biochemical effect, it may not show up on routine allergy tests, but there are other ways of testing.

Attention Deficit Disorder and Omega-3 Fatty Acids

Six months ago we discussed some of the research linking allergy, disturbances of cell membranes and attention deficit disorder with or without hyperactivity (ADD/ADHD). I also drew attention to the work indicating that there might be a role for omega-3 fatty acids in treatment, the essential fatty acid found primarily in seafood and flaxseed oil. The link between omega-3 fatty acids and ADD/ADHD has come from five lines of evidence:

- If animals are deprived of this nutrient, they become hyperactive and their offspring have reduced cognitive abilities

- Omega-3 fatty acids are essential to the normal growth of the brain

- Studies in animals indicate that changing the dietary intake of omega-3 fatty acids impacts the all-important dopamine systems of the brain

- Children who are breast fed have lower rates of ADD/ADHD, which is independent of any maternal characteristics ,and breast milk contains many essential nutrients including omega-3 fatty acids

- Anecdotes and some clinical trials of omega-3 fatty acids in children with ADD/ADHD, though we still don’t know the best way to supplement

Well, the research continues to come thick and fast:

- Omega-3 fatty acid deficiency may be involved in aggression, hyperactivity and conduct disorder, though the evidence is not as strong as it is for some other nutrients: Iron, zinc and protein deficiency all seem to contribute to aggressive, hyperactive behavior.

- Another recent study has found low levels of omega-3 fatty acids in children with ADHD.

- There seems to be an association between ADHD and a deficiecny of a key enzyme in fatty acid metabolism called fatty acid desaturase 1.

All of this led to the announcemet on Friday that the Murdoch Childrens Research Institute in Melbourne, Australia is recruiting for a clinical trial of the effects of omega-3 fatty acids on the brain function of children with ADHD. The study will examine the effects of these fatty acids on the learning skills, attention span, memory, reaction time and behaviour of 150 children with ADHD over 12 weeks. The effects will also be explored in 100 children without ADHD.

I am encouraged by the way in which the investigators plan to do this work, and I shall keep you posted as data – whether positive or negative – continues to emerge from this study and others.

Consequences

We have a new little kitten and this morning, despite trying to keep her in the house, she scooted outside and then ran into the local feline bully. The poor little creature came in with a nasty scratch on her ear, and perhaps the understanding that the world can sometimes be a scary place. We had tried to advise and guide her, put sadly she had to learn for herself that there can be unpleasant consequences from running outside.

Similary we all want the best for our children and the people around us, but sometimes we can do them harm if we don’t help them understand the consequences of their actions.

We teach children how to cross the road, and later on, how safely to drive a car and deal with dangerous or exploitative people. We can’t live their lives for them, but we can try to help them understand the consequences of their actions.

Sometimes this important gift fails to materialize when a child or other loved one is struggling with a chronic illness.

Let me explain.

During my clinical career I dealt with two groups of clinical problems in which the biggest difficulty was not diagnosis, but helping people to stay on the treatment that they needed. The two problems were diabetes and psychiatric illnesses. By treatment, I certainly don’t just mean taking medicines: I mean being able and willing to follow a course of action.

There are dozens of reasons why people decide against taking the treatment that they need, whether it’s surgery, medication, psychotherapy or homeopathic remedies.

- Some people don’t see the point of treatment: they are happy as they are even if the illness is causing unseen damage

- Others just forget their treatment

- Others don’t like the side effects, or they are frightened that they may get side effects

- People worry about stigma and about being seen as somehow different

- There are even a few who like being ill: not just the experience of, say, having lots of extra energy, but being cared for and looked after. I have known people who have spent 40+ years in bed, sometimes with quite minor problems.

- Some just deny that they are ill: The extent of the denial can be amazing.

I saw an article on the BBC this morning about a young woman who believes that she went blind from the complications of diabetes because she “rebelled” as a teenager and was probably in denial.

It reminded me of a young woman whom I was once treating. Her metabolic control was becoming worse and worse. She was getting blurred vision and she was rapidly gaining weight. Her mother became extremely indignant when I asked – very, very gently – if the young woman might be pregnant. The patient and her mother vehemently denied the possibility. Less than a month later – on Christmas Eve – I had to arrange for the teenager to have emergency laser therapy on her eyes for severe diabetic retinopathy. Four weeks later she gave birth to a healthy, but very large baby girl. Both mother and daughter were in denial until the very end, and mother did not want to help the daughter face the consequences of failing to treat her diabetes or the pregnancy.

I’d like to give you two other examples of failing to face consequences.

In the first, a family saw me on television and asked me to see their son. He had a major neurological illness, did not want to take medicine, and It turned out that he had already seen some of my colleagues in my department. The parents wanted me to force him into taking medicine.

The second involved someone with attention deficit disorder (ADD) who could not remember to take her treatment or to follow through with any of the therapies that we recommended. Her parents wanted us to treat her. After a while it became impossible, because she had no interest in being treated.

But here is the point. The young man with the neurological illness had something progressive. He could not yet be declared legally incompetent, but he could not see that without treatment he would become very sick. The young woman with ADD also had a potentially progressive illness and was on a slippery slope. Not that the ADD was becoming worse, but because the behavioral consequences of the illness were leading her into more and more risky behaviors.

In each case the parents wanted doctors and other therapists to “Do something.” Yet in each case the parents were probably the only people who could help their kids.

What do I mean by that? Some parents enable their children to avoid the consequences of refusing treatment. I asked the young man’s family what they did if he refused his medications? The answer was that they yelled at him. Yelling helps nobody. But they were aghast when I suggested that his treatment should be linked to having “privileges” at home.

If he truly genuinely needs help, and he can’t see it, sometimes the best way forward is for the person to have to face some consequences.

Whether or not he took his treatment, he might get yelled at, but after that he could go to his wing of the house, watch TV, play on his computer and order food. No

consequences. I suggested linking TV watching to participation in

treatment. The family would not countenance it. They wanted to displace

all the responsibility onto other people who should tell him what to

do. Yet they had unwittingly sabotaged every attempt at treatment in several

countries.

Treatment is a matter of discussion and agreement. And yes, of course, mentally competent people have a right to turn down treatment. But if they cannot see the consequences of their folly, then family and friends may be the only people with the leverage to help them.

Every one of us has wants and needs. If someone is stuck, then those wants and needs can help us to help them. This isn’t a matter of being coercive: it is sheer practicality.

The young man with the neurological problem saw no need for treatment because his every wish was being fulfilled: he even had servants waiting upon him. The young woman with ADD was probably not safe to be driving around in a car, yet her parents gave her one and paid for the gas and insurance anyway. They did not link treatment with providing all those things. So she saw no need to be treated.

Nobody wants to mean to a person suffering from an illness, but sometimes we need to mobilize all the resources that we have to help a person. It is entirely a matter of being pragmatic. The person saying, “Force my son to take his medicine,” is obviously speaking out of frustration. No clinician can or should do such a thing. Confrontation will scuttle any chance of setting up a therapeutic alliance with someone.

We do have some techniques for helping people. One very promising approach that we have been using is called motivational interviewing, and there are others. But even those will have little value unless people can see the advantages of treatment and the consequences of not being treated.

The best way of staying motivated to do something like stop smoking or manage your weight is to combine the advantages of taking action with the disadvantages of staying where you are.

If you know someone who has a real problem and is refusing help, ask if there is anything that you can do help motivate them to face the consequences of what they are doing. It can sometimes be the kindest and most loving thing that you can do for someone.

Industrial Chemicals and Autism

There is an exceedingly important article in this week’s issue of the Lancet, that has not yet received the attention that it deserves.

I have time and again discussed the extraordinary burden of artificial chemicals now born by the human body. None of which was present 100 years ago. It is not rocket science to ask whether this toxic burden may have soething to do with the the rise of many neurological and psychiatric illnesses, given the sensitivity of the growing brain to any kind of environmental insult.

The article, entitled “Developmental Neurotoxicity of Industrial Chemicals,” is written by two senior academics from Denmark who also hold positions at the Department of Environmental Health at Harvard School of Public Health, the Departments of Community Medicine and Pediatrics at Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York.

What they say is this. The report begins by saying that neurodevelopmental disorders such as autism, attention deficit disorder, mental retardation, and cerebral palsy are common and can cause lifelong disability. Indeed, 1-in-6 children has a developmental disability, which mostly affect the nervous system. The causes of these problems are largely unknown.

Secondly, the prevention of neurodevelopmental disabilities is hampered by the great gaps in testing chemicals for developmental neurotoxicity and the high level of proof needed for regulation.

Next, the list of potentially damaging chemicals is extremely long. A few industrial chemicals are recognised causes of neurodevelopmental disorders and subclinical brain dysfunction, for instance methylmercury, arsenic and lead. we simply do not know how manyother chemicals may affect the brain. Exposure to these chemicals during early fetal development can cause brain injury at doses that are much lower than those affecting adult brain function. Recognition of these risks has led to evidence-based programmes of prevention, such as the gradual elimination of lead additives in petrol. Although these prevention campaigns have been highly successful, most were initiated only after substantial delays. Another 200 chemicals are known to cause clinical neurotoxic effects in adults. That being the case, since the young brain is so much more sensitiv, we can only assume that many of these chemicals must also be dangerous to the fetus, baby and growing child.

This article is published at the same time as an investigative report in the National Geographic. The magazine paid $15,000 for a reporter to have a full toxicological analysis, and if you have any doubts about toxins, I would urge you to read the article.

As a side bar, many clinical practitioners offer different kinds of toxicological analysis based on hair, skin, blood or electrical testing. Some years ago we looked into many of these methods using confirmatory analyses using a full scale research laboratory at Northwick Park Hospital in London. We found very poor correlations between the results obtained by the laboratory and three labs doing hair and blood analysis. I’m sure that some labs do a good job using hair and other types of analysis for a good deal less than $15,000. But It’s good to be a little cautious before relying too much on some of these unorthox evaluations. Just ask the lab to give you the methods that they use, the standard errors of their testing, their false positive and false negative rates, and how often they get their results checked by an independent laboratory. Then you can be confident that you or your practitioner is using a good one.

The conclusion from all the published literature, some of which is summarized in the Lancet?

Environmental toxins are there, growing and they may be responsible for the catstrophic rise in some neurodevelopmental disorders, in particular autism.

We probably have enough empirical evidence toadvocate some serious cleaning up of the environment, which will likely only happen once people begin to vote with their feet. Governments are taking notice of global warming now that it is being suggested that it may damage national economies.

We need urgently to see whether, if the are present, we have – or can develop – viable methods for clearing these toxins from the human brain

and restoring normal structure and function.