Attention Deficit Disorder and Executive Functioning

“Not to have control over the senses is like sailing in a rudderless ship, bound to break to pieces on coming in contact with the very first rock.”

–Mahatma Gandhi (Indian Nationalist and World Teacher, 1869-1948)

The Mahatma’s statement could apply to most people stuggling with attention deficit disorder.

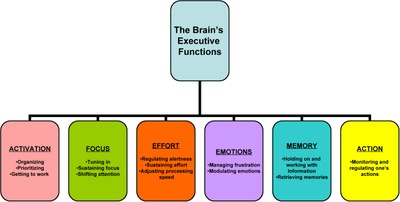

There is an important idea in neurology and psychology called “Executive functioning.” This refers to our ability to be able to make and carry out plans, direct our attention, focus and also to control our internal states: our impulses and emotions and to be able to switch from one task to another. In other words it is a key part of our ability to self-regulate our behavior, mind and emotions.

Most evidence now indicates that executive function is mediated by the regions of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. It happens that these same regions are amongst those that seem to undergo beneficial changes in people who practice meditation.

For people interested in attention deficit disorder, I’d like to recommend a book, “Attention Deficit Disorder: The Unfocused Mind in Children and Adults,” by Thomas E. Brown. In the book he encapsulates some up-to-date research indicating that one way of conceptualizing some of the difficulties faced by people with attention deficit disorder, is to break them down into the six major “domains” of executive functioning:

- Activation: Organizing, prioritizing and getting to school or work

- Focus: Tuning in, maintaining focus and shifting attention

- Effort: Sustaining effort, regulating alertness and adjusting processing speed

- Emotions: Modulating emotions and managing frustration

- Memory: Holding and manipulating information and retrieving memories

- Action: Monitoring and regulating actions

It can be very helpful for people to understand why they face the problems that they do, and how each may be amenable to a different type of help.

What we have done below is to re-draw and slightly simplify an extremely helpful diagram from Dr. Brown’s book, that will make it easier for you to see that kind of problems you or a loved one may be facing, and how treatment and coping strategies will be directed toward whichever of these is causing the most trouble in a person’s life.

(You can click on the diagram to see a large version of it.)

Food, Reward and Weight Gain

There’s a short review with a link to an online research paper that you might find interesting.

Although the paper has to do with the mechanisms of weight gain in people with schizophrenia, many of the same principles apply to many people with weight problems. The systems of the brain involved in salience – deciding what is important in the environment – appear to be disrupted.

Gene-Jack Wang at the Brookhaven National Laboratory has discovered that the brains of morbidly obese people seem constantly to be turned toward finding food: The regions of the brain connected to the mouth lips and tongue are overly active, and, like the addicts who get the biggest rush from drugs, they seem to have fewer dopamine receptors in the reward systems. Perhaps like the addict, the morbidly obese eat to compensate for an underactive dopamine system.

In Healing, Meaning and Purpose, we coined the term, “Salience Disruption Syndrome,” to describe a group of problems that are normally thought of as separate entities, but which are inextricably linked. They include not just over-eating, but:

- Impulse control disorders

- Substance abuse disorders

- Pathological gambling

- Pathological shopping

- Attention deficit with ot without hyperactivity

- Bipolar disorder

The list is a long one and the reason for highlighting it is that we have been able to devise new treatments based on this new principle of a disruption in salience. If there is interest, I shall post some more about the methods that we have devised.

Cutting and Self-injury

There’s an extremely disturbing trend: ever-increasing numbers of young people who are cutting themselves. Once rare, and something usually seen only in people with serious psychiatric illness, many school children encourage and goad each other into doing it, and there are websites dedicated to cutting, on which young people compare notes and even give each other advice on how to conceal what they are doing, by cutting themselves in places like the lower back.

We have been offered a great many explanations for this worrying development, but not much in the way of evidence. We know that most people who cut themselves are female adolescents or young adults, and apart from the obvious physical dangers, there is evidence that this behavior may lead to a more serious psychological condition called Borderline Personality Disorder. This can be a serious problem that carries a high risk of suicide. It is also of some theoretical interest, because there seem to be genuine cultural differences in borderline personality disorder. An estimated 5.8 million to 8.7 million Americans, mostly women, suffer from it, but it is far less common in most of Western Europe and Australia. Research over the last decade has indicated that the condition is becoming more common in these regions. People with the borderline personality disorder have a wide spectrum of difficulties that are marked by emotional instability, difficulty in maintaining close relationships, eating disorders, impulsivity, chronic uncertainty about life goals and addictive behaviors such as using drugs and alcohol. They also have major impact on the medical system by being among the highest users of emergency and in-patient medical services. Glen Close’s character Alex Forrest in the movie Fatal Attraction, had some of the features that we might expect in some with borderline personality disorder.

Researchers from the University of Washington in Seattle have reported that adolescent girls who engage in cutting behavior have lower levels of the chemical transmitter serotonin in their blood. They also have reduced levels of activity in the parasympathetic nervous system as measured by what is called respiratory sinus arrhythmia, a measure of the ebb and flow of heart rate as we breath. Low levels of this measure are typically found in people who are anxious or depressed. The study included 23 girls aged 14 to 18, who engaged in what psychologists call “parasuicidal” behavior. Participants were included if they had engaged in three or more self-harming behaviors in the previous six months or five or more such behaviors in their lifetime. The comparison group consisted of an equal number of girls of the same ages who did not engage in this behavior.

In line with previous research, the adolescents in the parasuicide group reported far more incidents of self-harming behavior than did their parents.

The findings of low serotonin and low parasympathetic activity support the idea that the inability to regulate emotions and impulsivity can trigger self-harming behavior. The primary problem is an inability to manage their emotions: the people who cut themselves have excessively strong emotional reactions and they have extreme difficulty in controlling those emotions. Their self-harming behavior may serve to distract them from these emotions.

A characteristic feature of borderline personality disorder is not just self-injurious behavior but also stress-induced reduction of pain perception. Reduced pain sensitivity has been experimentally confirmed in patients with the condition. The increasing incidence of the condition in Europe is attracting many European investigators and colleagues from Mannheim in Germany have recently traced the neurological circuits involved in this stress-induced reduced pain perception.

There is good evidence that people who cut themselves are more likely to have been victims of sexual abuse or violence as children, though that obviously does not mean that every person who harms themselves has had something bad happen to them in childhood. Sadly the research has become more complex because of the numbers of people who have been given false memories of abuse by well-meaning psychologists.

Treating people who cut themselves, whether or not they have borderline personality disorder can be very challenging. The first thing is to treat any underlying mood or anxiety disorder. A combination of medications and psychotherapy is normally used, with people making claims for the value of different types of therapy. Many therapists also say that they have helped people who cut themselves with tapping therapies, acupuncture, homeopathy and qigong. I’ve not been able to find any credible research evidence to support the use of those therapies, though I’ve also seen some success stories.

We also have the puzzle about why cutting and borderline personality disorder seems to have been less common in other parts of the world and are now increasing. There is research to show that it’s not just a matter of recognition or of calling the illness something else in Europe. I have a friend who is a senior academic at an Ivy League University, and an expert on borderline personality disorder. During a sabbatical in Scotland some 15 years ago, he could not find a single case. This matters, because if we can identify what’s changed, we may have some clues about treatment. There are hundreds of candidates, including environmental stress, diet and toxins.

There’s an important new study in which 13 children with autism showed marked improvement in some of their challenging behaviors when they were given 1.5gms of omega-3 fatty acids each day. This was only a six week study, but it needs to be replicated using larger numbers. It is also important to be alert to the possibility that some makes of omega-3 fatty acids on the market contain mercury. The one that we have found best so far has been OmegaBrite. http://www.omegabrite.com/ It will also be useful to see if dietary supplementation will help self-injurious behavior in other types of people.

Here is a list of some of the better information sites about self-harm.

The key to success with helping complex problems, as I point out in great detail in Healing, Meaning and Purpose, is a comprehensive approach:

Combinations are Key

Heroes and Villains

“Nothing is as infectious as example.”

–François Duc de la Rochefoucauld (French Writer and Moralist, 1613-1680)

I was just expecting to learn something about what’s been going on in the world today, when I came across this excellent blog item by Chess Grandmaster Susan Polgar.

Just have a look at this extraordinary video.

What amazed me just as much as the video, was that one of the commentators on Susan’s blog defended the action of the adult, on the grounds that the assaulted child had played a foul, saying, "As a parent, how easy would you find it to stand by if that happened to your kid?"

The answer to that should be, "Very easy indeed."

Adults are supposed to have some modicum of self-control.

Adults also have a responsibility to model good behavior, not just for their own children, but for all other children as well.

It reminded me of the quotation:

"If you can’t be a good example, then you’ll just have to be a horrible warning."

–Catherine Aird (a.k.a. Kinn Hamilton McIntosh, English Writer and Creator of “Inspector Sloan”, 1930-)

I’ve been involved in competitive games for most of my life, and of course they can inflame emotions. But it is how we act on those emotions that matters. I used to have an excellent chess coach named Craig Jones. He has done a lot for scholastic chess, and I remember being horrified by the antics of some parents at chess tournaments. Those scenes from the movie Searching for Bobby Fischer are not an exaggeration.

Being a victim of your emotions is bad enough. Being a lousy role model is the worst kind of irresponsibility.

I actually prefer another term to "role models." I call them heroes. And the opposite of a hero is, I suppose, a villain.

“Young people need models, not critics…”

–John Wooden (American Basketball Coach, 1910-_

People Dangerous to Your Health

I found a terrific blog with the title “Warning: Bores and buffoons may endanger your health.”

Our ability to self-regulate is a limited resource that fluctuates markedly, depending on our prior use of willpower, tiredness, stress and our personal resilience.

A new study by a team lead by Professor Eli Finkel of Northwestern University has shown that poor social coordination impairs self-regulation. What does this mean? If you are forced to work or interact with difficult individuals you may be left mentally exhausted and far less able to do anything useful for a significant period of time. In other words, draining social dynamics, in which an individual is trying so hard to regulate his or her behavior, can impair success on subsequent unrelated tasks.

In the research, volunteers were asked to work in pairs to maneuver an icon around a computer maze, with one volunteer giving the instructions, the other moving the joystick. Those operating the joysticks were actors, primed to respond to instructions in slow, stupid, inefficient and generally irritating ways. What was interesting was that the effects were not mediated through participants’ conscious processes: they were almost entirely going on below the level of conscious awareness.

There is extensive literature on the consequences of social conflict. But until now, very little research has been conducted on the effects of ineffective social coordination. That has been a big gap in the research literature, particularly given the fact that most of the higher systems in our brains are dedicated to social functions, and since the earliest days of our hunter-gatherer ancestors, tasks requiring social coordination have been the norm. In our day-to-day activities we have to cooperate with other people. Ineffective social coordination consumes a great deal of mental resources and has high costs for subsequent self-regulation. This is so important, because self-regulation is essential to living life well. It is also essential to the existence of a well functioning society.

What to do with this new information?

Identify people who drain you. If you need to work with them, do it in short bursts, and give yourself plenty of time outs.

And continue to build your resilience.

There’s also one other piece, that we’ll look at another time. Some people may also drain your energy directly. You may have come across "energy" or "psychic vampires." They really do exist, though there is nothing supernatural about them, and they don’t have fangs or an aversion to garlic. In another post I’ll show you some techniques for dealing with those people as well.

The researchers have done us a great service by putting the entire paper on the departmental website. Access is free.