Wise Words About Leadership

I was recently talking to someone about the difference between managers and leaders. Wherever you find yourself with a group of people who have to get something done, you can usually spot the leaders. They don’t necessarily have lots of stripes on their arms, distinctive epaulettes or shiny nameplates. For more than two centuries it has been known that around 5% of the population has a natural ability to lead. But more importantly others give them the permission to take charge. That 5% also has a number of other interesting characteristics that we shall talk about in other posts.

But there is more to leadership than natural ability.

Here are some wise words from someone who know more than most about successful leadership:

“Is leadership inherent or trainable? Both.

You are born with characteristics that reside deep inside you: drive, an ability to influence and motivate, perseverance. But you have to develop those qualities through actual leadership experiences.

A key quality is adaptability–facing unexpected obstacles, falling short of goals, reading the context, and changing your approach.

Absent that, leaders will continue to repeat mistakes and will not grow and develop. That leads me to the essence of the question “Why is it so hard to lead yourself?”

The answer, in my experience, lies in the differences between your idealized self–how you see yourself and how you want to be seen–and your real self. The key to growing as a leader is to narrow that gap by developing a deep self-awareness that comes from straight feedback and honest exploration of yourself, followed by a concerted effort to make changes.”

–William W. George (American Professor of Management Practice at Harvard Business School and Former CEO of Medtronic, Inc., 1942-) [Quoted in Fast Company, April 2007]

Learning By Example

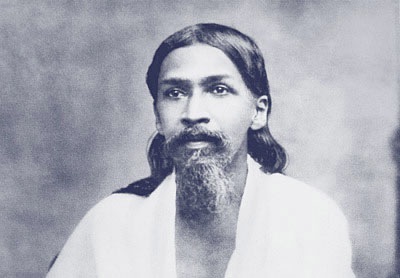

“Perfect health, sincerity, honesty, straightforwardness, courage, disinterestedness, unselfishness, patience, endurance, perseverance, peace, calm, self control are all things that are taught infinitely better by example than by beautiful speeches.”

–Sri Aurobindo (a.k.a. Aurobindo Ghose, Indian Nationalist Leader, Mystic, Philosopher and Creator of Purna (Integral) Yoga, 1872-1950)

Mastering Chess: Genes or Environment?

It is always interesting to look at people who have excelled at something to see what we can learn.

I recently talked about the new research indiating that there are some genes that have some impact on intelligence.

There is an interesting article in today’s New York Times, entited, “Nature? Nurture? Never Mind. Here’s a Sister Act to Watch,” by Dylan Loeb McClain. He has this to say:

“Siblings who are elite chess players are rare. The best known are probably the Polgar sisters of Hungary. Susan, the eldest, is a grandmaster and former women’s world champion. Sofia is an international master. And Judit, the youngest, is the best woman player in history.

Other notable chess-playing siblings have included the Byrne brothers, Robert, a grandmaster and the longtime columnist for The New York Times, and Donald, an international master who died at 45; and Gregory Shahade, an international master, and Jennifer Shahade, a two-time United States women’s champion, who were taught chess by their father, Michael, a master.

Why so few elite sibling players? Is it simply because it is highly unlikely for a single family to produce multiple elite players? Or do most siblings have different interests?

The questions go to the heart of a familiar debate: Is chess talent innate or nurtured?

In his popular book “The Immortal Game,” David Shenk said great chess players were made, not born, writing, “Cognitive chess research punctured the longstanding myth of the chess prodigy, the born genius.”

The best players, Shenk wrote, are the product of intensive study and training. He said the Polgar sisters, who were raised by their father, Laszlo, from an early age to be chess players, were a prime example.

Shenk recounts an episode years ago in which Susan was studying with an international master and they had a problem they could not solve. They woke up young Judit, who, half-asleep, found the solution immediately and went back to bed.

Aren’t the varying levels of talent among the Polgar sisters, who all presumably had the same training, evidence of innate differences? Possibly.

A pair of sisters who have been making a big splash lately do not seem to be separated by ability, at least so far. Nadezhda and Tatiana Kosintseva of Russia are ranked No. 14 and No. 24 in the world among women. But at the European championships, which concluded April 15, Tatiana ran away from a large field, finishing two points ahead of her sister.”

There is undobtedly some set of genes that increase the chance that someone will be good at some game or other, whether it is chess or golf. But there is also the family, school or club that can help someone to realize their true potential.

But even if the genes aren’t all there, you can still become highly competent if you have learned how to learn and if you have learned the arts of patience, perseverance and persistence.

Biology is not destiny!

Creativity and Resilience

“No great thing is created suddenly, any more than a bunch of grapes or a fig. If you tell me that you desire a fig, I answer you that there must be time. Let it first blossom, then bear fruit, then ripen.”

–Epictetus (Phrygian-born Greek Stoic Philosopher, c.A.D.55- c.A.D.135)

I have written several articles about resilience, and I have begun to talk about some of the methods for developing psychological resilience and also some of the potential consequences of not developing this essential psychological strength.

I’d also like to share with you another aspect of resilience: it is essential ingredient of creativity and of innovation.

I’ve had a longstanding fascination with the creative process, and one of the most robust findings in the research on extraordinary creative achievement is that even the greatest performers in their fields seem to produce the same ratio of undistinguished works to notable ones through their careers. The great chess player wins more often than the average one, but only sometimes produces a truly great creation. Even the best engineers and scientists conduct many unsuccessful experiments. The stories are legion of artists who produce many paintings and works of music that never win recognition and may not even be much good. Many great actors, directors, cricketers and companies have a great many failures behind – and sometimes in front – of them.

Amongst the many attributes of the high achiever in each of these fields is a remarkable ability to bounce back, to detach from the apparent failure, to see it as an education, and to understand the importance of persistence and perseverance. To take a risk, to take a step back and to learn and adapt if at first it doesn’t succeed. This never means repeating the same strategies over and over again, it means being smart and not being fazed by failure

“Unless you are willing to try, fail miserable, and try again, success won’t happen.”

–Phillip Adams (Australian Broadcaster, Filmmaker, Archaeologist and Satirist, 1939-)

I was once working with a company that had just tried to launch a promising new medicine. The initial effort had been a flop and at the time that I became involved, the company had just fired the entire marketing team. Neither the company nor the recently departed team had had the chance to find out what had gone wrong and how to build something new and different. The new team had to start from scratch and, living in constant fear, was burning out at an astonishing rate. The real problem was the inflexibility of the company that was stifling creative solutions to problems. Once that was fixed, things began to improve very quickly.

If anyone ever says that they and the company never accepts failure, it is laudable but impractical.

It’s different if an enterprise fails because people are not pulling their weight; or failing to meet deadlines; or being overly rigid in interpreting rules or just goofing off. But if everyone is trying to help, learning, and being dynamic and flexible, then it’s best not to send them on their way, but instead to see how we can learn from a failure.

And the key for you personally and the key for your company is to learn to develop personal and corporate resilience. Then creative answers have the chance to start flowing.

“Results! Why, man, I have gotten a lot of results. I know several thousand things that won’t work.”

–Thomas Alva Edison (American Inventor, 1847-1931)

“No one succeeds without effort…. Those who succeed owe their success to their perseverance.”

–Ramana Maharshi (Indian Hindu Mystic and Spiritual Teacher, 1879-1950)