Consciously Using Time

“When you consciously use time

To do something Divine,

You enter into timeless Time.

When you are consciously thinking

Of something divine, eternal Life come

And shakes hands with you.”

–Sri Chinmoy (a.k.a. Chinmoy Kumar Ghose, Indian Philosopher and Spiritual Teacher, 1931-2007)

The Value of Moments

“The value of moments, when cast up, is immense, if well employed; if thrown away, their loss is irrevocable.”

–Philip Dormer Stanhope, 4th Earl of Chesterfield (English Statesman and Author, 1694-1773)

Steps Toward Knowledge of the One

“The three mental steps towards knowledge of the One Reality are:

1. Listening

2. Reflecting

3. Contemplating

Listening means paying attention to the statements of the Scriptures with reference to the One Reality, and also to the words of seers and sages on the subject.”

–Ernest E. Wood (English Theosophist, Yoga Practitioner, Translator, Author and Professor of Physics, Principal and President of the Sind National College and the Madanapalle College, India, 1883-1965)

Close Your Eyes and I’ll…

Every young neuroscience student learns about a classic experiment that was published in 1956 by Raul Hernandez-Peon, in which he had an electrode in the acoustic nerve of a cat, while a metronome was ticking. Every tick caused a pulse of electricity in the nerve. But as soon as the cat saw or smelled a mouse, the electrical activity plummeted: now all of his attention was on lunch, and his brain damped down the unnecessary ticking of the metronome. Something similar happens with the “Cocktail Party Phenomenon:” our ability to focus our listening attention on a single talker and ignoring other conversations that are going on.

A study by researchers from Wake Forest University Baptist Medical Center and the University of North Carolina was presented at the Society for Neuroscience conference in San Diego this week, suggesting that our brains can turn down our ability to see, so that we are better able to listen and focus on music and complex sounds.

The research used functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging in 20 non-musicians and 20 musical conductors aged 28-40, and found that both groups diverted brain activity away from visual areas during listening tasks. The activity fell in the visual regions areas as it rose in auditory ones. But during harder tasks the changes were less marked for conductors than for non-musicians.

While being scanned the subjects were asked to listen to two different musical tones played a few thousandths of a second apart and identify which was played first. The task was made harder for the professional musicians than for the non-musicians, to allow for the differences in their background.

As the task was made progressively more difficult, the non-musicians carried on diverting more and more activity away from the visual parts of the brain to the auditory, as they struggled to concentrate on the music. However, the conductors did not suppress their brains, suggesting that their years of training had given them an advantage in the way that their brains were organized and functioning. They are less likely to be distracted and are highly tuned to musical sounds.

This is like closing your eyes to listen to music and the advantage of the trained musicians is similar to the advantage that we see in the brain of the chess master compared with the amateur. Years of study and practice enable the chess player to move without much conscious thought.

It shows how well we are able to divert activity from one part of the brain to another as needed. It is that ability to be flexible and to recruit more brain when we need it that lies at the heart of the neurocognitive revolution that is changing the way that we think about the brain and mind.

Zen and the Aging Brain

The two main kinds of meditation that have received a lot of research attention are Zen and Transcendental Meditation. Both produce measurable physiological changes and both may produce changes in the brain.

Zen meditation is centered on attentional and postural self-regulation.

As we age, there is normally some decline of cerebral gray matter volume and attentional performance. As I have pointed out, those changes do not necessarily mean a decline in functioning, but simply a change.

In a new study researchers here in Atlanta examined how the regular practice of meditation might affect the brain. The researchers studied 13 regular practitioners of Zen meditation and 13 matched controls.

They used some sophisticated techniques to calculate the volumes of different regions of the brain. They also performed a computerized sustained attention task.

While the control subjects showed the expected negative correlation of both gray matter volume and attentional performance with age, the meditators did not show a significant correlation of either measure with age.

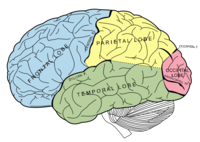

Interestingly, the effect of meditation on gray matter volume was most prominent in a region of the brain called the putamen, a system of the brain that is strongly implicated in attentional processing.

These findings are intriguing and are consistent with some of the research done in Richard Davidson’s laboratory in Wisconsin, that looked at people practicing a different form of meditation, but also showed that expert meditators produce both structural and functional changes in their brains.

The study on aging suggests that the regular practice of meditation may have neuroprotective effects and reduce the cognitive decline associated with normal aging.

If that is confirmed, I think that we have something else to add to our list of “things to do to reduce your risk of getting Alzheimer’s.”

Brain Training and the Paradox of Aging

For centuries, people in cultures throughout the world have believed that increasing age is associated with increasing wisdom. Not just knowledge and experience, but wisdom. Is this an old wives’ tale, or is there something to it?

There is growing evidence that as we age our brains actually become stronger. Everyone missed it, because the emphasis was on memory, concentration and thinking speed, and those may all deteriorate with age. What changes is that as we age we become more efficient at making associations rather than thinking linearly. we also recruit regions of the brain that may have lain dormant for years. At the same time, different types of mental training, including meditation, can improve many aspects of our cognitive abilities, and may also enrich and even grow appropriate regions of the brain.

Some new data from a study being conducted at Wake Forest University Baptist Medical Center in North Carolina suggests that it is possible to use a fitness program for your brain that can improve thinking skills, attention and concentration as reliably as lifting weights can increase muscle strength.

Preliminary findings from the study, which used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to record brain activity, were presented last week at the Organization for Human Brain Mapping conference in Chicago.

As we age, we do experience changes in how we perceive the information that our senses gather from the environment. As I mentioned older adults combine information from the different senses more readily than do younger adults. This is known as sensory integration, and the down side is that it can lead to difficulties in blocking out distracting sights and sounds while still maintaining focus on important information. You are probably familiar with the “Cocktail Party Phenomenon.” You are in a loud room, but because someone is saying something interesting, you are able to block out uninteresting information. This technical term for this is cortricofugal inhibition. As we get older it gets more difficult to do the inhibiting.

The Brain Fitness in Older Adults (B-fit) study has been designed to establish whether eight hours of brain exercise can improve the ability of healthy older adults, ages 65 to 75 years, to filter out unwanted sights and sounds.

The B-fit study uses fMRI to visualize blood flow and brain activity to determine how attention training affects brain function. The training involves either a structured one-on-one mental work-out program or a group brain exercise program. During the one-on-one sessions, the volunteers were asked to ignore distracting information and tasks get harder as the eight-week training progresses. For the group sessions, participants learn new information relevant to healthy aging and are then tested on their ability to apply the new information.

All participants had an fMRI scan during a distraction task. They had to look for target words or numbers while ignoring distracting sounds. The scans showed brain activity in areas related to both sight and sound. Follow-up fMRIs showed that in the group receiving the one-on-one training, activity related to sight was increased, while activity related to sound was decreased. In addition, performance on the task was improved.

So the data do indeed suggest that attention training is a way to reduce

older adults’ susceptibility to distracting stimuli and therefore help improve

concentration.

And what about wisdom?

I have written in Healing, Meaning and Purpose that “Wisdom is the integration of understanding:” making more new associations and drawing conclusions based on a new perspective is a gift of aging. The training enables us to make sense of and communicate our conclusions.

When it comes to the brain, use it or lose!

Meditation and Learning to Pay Attention

I have talked before about the increasing difficulties that we all have with paying attention.

Over the years we have tried all sorts of things to help people to become better at focusing and controlling their attention, from games, to biofeedback devices to meditation. It is the last of those that seems to be the most effective.

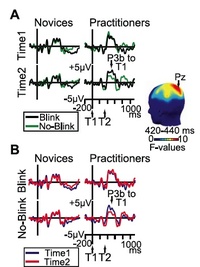

We know from personal experience that paying close attention to one thing can keep us from noticing something else. If we are shown two visual signals half a second apart, we usually miss the second because we are still focused on the first one. We are consciously unaware of the second flash. It is rather like missing something when we blink our eyes, and indeed psychologists call it “attentional blink.” Many psychologists have assumed that attention is something fixed: we can only give a certain amount of attention to one thing at a time before we have to move onto something else or get a kind of brain freeze.

But we have known for some time now that sometimes people do notice the second flash of light, and with practice they can notice it all the time, suggesting that the limitation on seeing the two flashes is not entirely physical, but that it may be possible to bring it under mental control. The first style of meditation that I ever learned was Vipassana, and I well remember being astonished at how quickly my attention and focus began to improve, even when I was not meditating.

Now there is an important new study from the University of Wisconsin-Madison that suggests that attention does not have a fixed capacity, and that it can be improved by directed mental training such as meditation.

The work was done in Richard Davidson’s lab at the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Medicine and Public Health and the Waisman Center for Brain Imaging and Behavior and published online in the journal PLoS Biology. (This is one of the growing number of open access journals, and for people not yet convinced of the value of open journals have a look at this paper, in which everything is available to you for free.)

The investigators recruited people who were interested in meditation to study whether conscious mental training can affect attention.

They examined the effects of three months of intensive training in Vipassana meditation, which focuses on reducing mental distraction and improving sensory awareness.

Volunteers were asked to look for target numbers that were mixed into a series of distracting letters and quickly flashed on a screen. As subjects performed the task, their brain activity was recorded with electrodes placed on the scalp. In some cases, two target numbers appeared in the series less than one-half second apart – close enough to fall within the typical attentional blink window.

The researchers found that the three months of rigorous training in Vipassana meditation improved people’s ability to detect a second target within the half-second time window. In addition, though the ability to see the first target did not change, the mental training reduced the amount of brain activity associated with seeing the first target.

Because the subjects were not meditating during the test, their improvement suggests that prior training can cause lasting changes in how people allocate their mental resources.

As Richard Davidson says,

“Their previous practice of meditation is influencing their performance on this task. The conventional view is that attentional resources are limited. This shows that attention capabilities can be enhanced through learning.”

The finding that attention is a flexible skill opens up many possibilities. It provides further evidence that attention training is worth examining for attentional problems such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

“When we raise ourselves through meditation to what unites us with the spirit, we quicken something within us that is eternal and unlimited by birth and death. Once we have experienced this eternal part in us, we can no longer doubt its existence. Meditation is thus the way to knowing and beholding the eternal, indestructible, essential center of our being.”

–Rudolf Steiner (Croatian-born Austrian Mystic, Occultist, Social Philosopher, Architect and Founder of Anthroposophy, 1861-1925)

“The moment one gives close attention to anything, even a blade of grass, it becomes a mysterious, awesome, indescribably magnificent world in itself.”

–Henry Miller (American Writer, 1891-1980)

“The path of spiritual attention is not easy, although anyone can make a beginning by trying to understand.”

— Sri Raghavan Iyer (Indian-born Prodigy, Rhodes Scholar, Academic, Philosopher, Theosophist, and, from 1965-1986, Professor of Political Science at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and Father of Pico Iyer, 1930-1995)

Brain-Derived Growth Factors and Bipolar Disorder

As we are learning more about the plasticity of the brain, and the way in which new neurons can continue to grow throughout life, there is a great deal of interest in factors that stimulate the growth or development of neurons. This is particularly important in condition like schizophrenia and bipolar in which cognitive decline may occur.

Researchers from Portugal presented some interesting new data (NR68) on Monday at the 2007 Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association in San Diego, California.

Genetic and pharmacological studies have suggested that brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), one of the most common neurotrophic factors in the brain, may be associated with the pathophysiology of bipolar disorder. The data has been a bit of a mixed bag: previous studies have suggested that BDNF may be associated with either a worse or better neurocognitive outcome in tests of frontal lobe function.

The researchers examined 28 people with bipolar disorder whose mood was currently normal: i.e. they were euthymic, and they compared them with 25 healthy volunteers. They measured BDNF levels and performed a battery of neuropsychological tests.

The people with bipolar disorder had clear evidence of problems with attention and executive function even when their mood was normal. However it does not seem to have much to do with BDNF: the levels were the same in both patients and healthy volunteers. There was an association between BDNF levels and memory in people with bipolar disorder. This makes sense: BDNF has been implicated in the formation of memory traces in the brain.

What this means is that problems of attention and executive function are likely to be trait-markers of bipolar disorder, while BDNF levels may be a state-related biological marker.

It is interesting how the wheel keeps turning: the person who first differentiated dementia praecox (schizophrenia) from manic depression (bipolar disorder) was Emil Kraepelin. He originally said that people with dementia praecox became worse over time, because of progressive cognitive decline, while people with manic depression did not. When he passed away in 1926 he was working on a whole re-visioning of mental illness, saying that the two could not be so clearly differentiated, because cognitive decline could occur in either illness.

Many pharmaceutical companies are looking into the possibility of improving cognition in major mental illnesses, but there are also a great many non-pharmacological interventions that can be done to help cognition in people with major mental illness.

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: Diagnosis and Complications

I have had a great many requests to talk more about attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): what it is, and what it is not; when is it a problem and when is it just “normal” childhood or adolescent behavior? And what evidence is there for non-pharmacological approaches?

Although there is a lot of information about ADHD available in books and on line, some is better than others, and some is misleading. I have recently had the privilege of giving a series of lectures on each of these topics, and many people have thought that I had a different take on the issue, so I an going to summarize some of the lectures here.

First I would like to direct you to a short article on the diagnosis on ADHD. The most important point is that we have to tell the difference between kids being kids and a problem that needs treatment.

Second is an article that talks about some of the problems that may follow if someone has ADHD and it is not diagnosed or treated.

Over the next two days I am going to follow up with articles that I have written on "Non-pharmacological and Lifestyle Approaches to Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder":

Diet, nutrition, allergies and sensitivities

Herbs and supplements

Movement, exercise, sleep and environmental design

Massage, qigong, tapping therapies and acupuncture

Mind-body approaches to treating ADHD

Homeopathy and flower essences in ADHD

Using Integrated Medicine in ADHD

“Thoughts of themselves have no substance; let them arise and pass away unheeded. Thoughts will not take form of themselves, unless they are grasped by the attention; if they are ignored, there will be no appearing and no disappearing.”

–Bhikshu Ashvaghosha (Indian Playwright and Master of Buddhist Philosophy, c. A.D. 1st Century)

“The true art of memory is the art of attention.”

–Samuel Johnson (English Biographer and Essayist, 1709-1784)

“Attention makes the genius; all learning, fancy, and science depend upon it. Newton traced back his discoveries to its unwearied employment. It builds bridges, opens new worlds, and heals diseases; without it taste is useless, and the beauties of literature are unobserved.”

–Robert Aris Willmott (English Author, 1809-1863)

A Possible New Treatment for Attention Deficit Disorder

Although I am always eager to use non-pharmacological treatments whenever possible, sometimes it just isn’t possible to us them on their own. I’ve outlined some of the reasons for treating attention deficit disorder (ADD) in a previous post.

We should soon hear whether the regulatory authorities in the United States and Europe are going to approve a medicine – guanfacine – that we currently use for treating high blood pressure, for the treatment of ADD. In the United States it is currently sold under the trade name Tenex. The medicine works in the brain by modulating a population of receptors known as the central nervous system α-2 adrenergic receptors, which results in reduced sympathetic outflow leading to reduced vascular tone. Its adverse reactions include dry mouth, sedation, and constipation.

The idea of using a medicine like this for treating ADD is not new. Fifteen years ago researchers showed that receptor agonists like clonidine decreased distractibility in aged monkeys. And clonidine itself has occasionally been used for treating ADD for over twenty years.

Guanfacine seems to have some unique properties including decreasing the activity in the caudate nucleus while increasing frontal cortical activity. We would therefore expect it not only to help with ADD symptoms, but it may have some quite specific properties relating to learning new material. A key point is that if approved it will only be the second nonstimulant medicine for ADD, along with atomoxetine (Strattera). Many clinicians have had a lot of trouble with side effects of atomoxetine, particularly if it is used in adult men. So if guanfacine is approved, and if it does not have the same side effects, that would be a big bonus.

New options are always welcome, but it remains important for any new pharmacological treatment to be nested in an Integrated approach, which always includes nutrition, physical and cognitive exercises, psychological and social help, as well as attending to the subtle and spiritual aspects of the problem.

And ADD can be a very big problem, despite the protestations from people who claim that it is a non-disease dreamed up by pharmaceutical companies. Our interest is not just professional, but personal. Every single day we see what can happen if someone forgets their medicine.

If the FDA gives approval for guanfacine I shall immediately report it for you, as well as giving you details of all the safety and tolerability data.