The Heart Master Cells

There are two extremely important papers (1, 2,) in this month’s issue of the journal Cell.

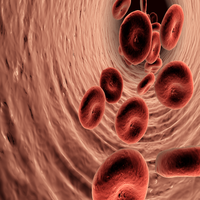

The heart is composed of three major types of cell: Cardiac muscle cells that make up the heart itself and whose contractions pump blood; smooth muscle that cells that are found in the walls of the heart’s own blood vessels and finally endothelial cells that line the heart’s blood vessels. There are many other special types on neural and endocrine cells in the heart, but these three form the basis of the circulatory pump that keeps you alive.

In one of the papers, scientists identified a cell that has the capacity to produce all three major tissues in the heart, the other group found a cell that produces two of the three cell types. One appears to generate structures on the left-hand side of the heart, and the other on the right-hand side. The findings challenge the old idea that the heart’s different cell types are so different that they must have come from separate sources.

What this means is that some unknown mechanism can make a single stem cell “decide” to become one of the three cell types.

Until very recently it was assumed that there was no way that a damaged heart or brain could regenerate itself. We now have proof positive that this dogma is wrong and it raises some extraordinary possibilities for repairing the heart.

These new papers follow others that have worked out the mechanism by which a little creature common in the tropics – the zebrafish – is able to mend his heart if it gets broken, and some research published in the journal Nature that showed that a molecule called thymosin beta-4 can make progenitor cells in the outer layer of the heart migrate deeper into the heart and carry out repairs.

My old friend Professor Jeremy Pearson – with whom I shared a lab and an office for seven years – is now the Associate Medical Director of the British Heart Foundation, and he had this to say about the second of those papers:

“By identifying for the first time a molecule that can cause cells in the adult heart to form new blood vessels, Dr Riley’s group have taken a large step towards practical therapy to encourage damaged hearts to repair themselves, a goal that researchers are urgently aiming for.”

And Professor Colin Blakemore, the chief executive of the British Medical Research Council, said:

”Finding out how this protein helps to heal the heart offers enormous potential in fighting heart disease, which kills more than 105,000 people in the UK every year.”

Jeremy Pearson was very helpful when I first started fleshing out and presemting the ideas about the reversibility of problems like arteriosclerosis, ischaemic heart disease, stroke and Alzheimer’s in the late 1980s. He was initially very skeptical, but did what a good scientist should. He didn’t shut down the discussion but kept it going with challenging questions.

The important point from all this research is not just that it supports many of the basic concepts of Integrated Medicine, but it also reminds us that when someone says that a disease is untreatable or irreversible, they may well be wrong.