Riding the Whirlwind

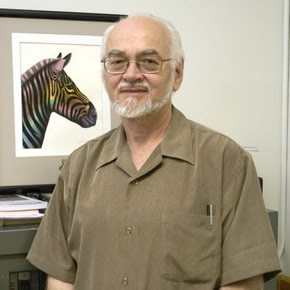

“In emotional turmoil, the upward influences of subcortical emotional circuits on the higher reaches of the brain are stronger than topdown controls. Although humans can strengthen and empower the downward controls through emotional education and self-mastery, few can ride the whirlwind of unbridled emotions with great skill.”

–Jaak Panksepp (Estonian-born American Psychologist, Neuroscientist and Baily Endowed Chair of Animal Well Being Science for the Department of Veterinary and Comparative Anatomy, Pharmacology, and Physiology at Washington State University’s College of Veterinary Medicine, 1943-)

Before You Try to Meditate

Anyone who has taught any form of meditation, t’ai chi ch’uan or one of the many other spiritual paths knows that this is absolutely true:

“All too often the mistaken belief that enough sincere practice of prayer or meditation is all that is needed to transform their lives has prevented teachers and students from making use of the helpful teachings of Western psychology. In an unfortunate way, many students of Eastern and Western spirituality have been led to believe that if they experience difficulties, it is simply because they haven’t practiced long enough or somehow have not been practicing according to the teachings. . . .

In truth, the need to deal with our personal emotional problems is the rule in spiritual practice rather than the exception. At least half of the students at our annual three-month retreat find themselves unable to do traditional Insight Meditation because they encounter so much unresolved grief, fear, and wounding and unfinished developmental business from the past that this becomes their meditation.”

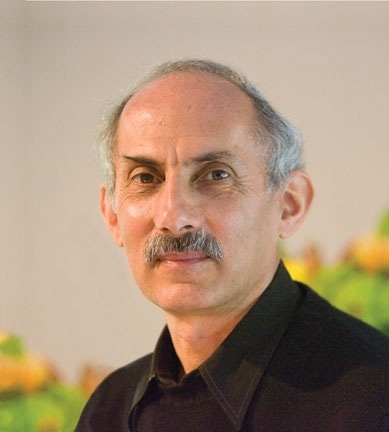

–Jack Kornfield (American Meditation Teacher in the Theravadan Buddhist Tradition, 1945-)

Do You Get Frustrated?

“Frustration stems from the nasty habit of allowing the ego to decide the timing and delivery of its desires. If you blindfold the ego with discipline and never show it the menu of life, it doesn’t bitch about the food – it’s thrilled that you are eating to keep alive.”

–Stuart Wilde (English-born Author, Lecturer and Humorist 1946-)

The Power of Your Heart

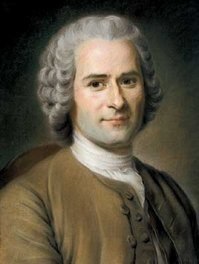

“Nothing is less in our power than the heart, and far from commanding we are forced to obey it.”

–Jean-Jacques Rousseau (Swiss-born French Philosopher, 1712-1778)

Emotional Eating

A new study from Miriam Hospital’s Weight Control and Diabetes Research Center in Providence, Rhode Island, has just been published in the journal Obesity. The research suggests that dieters who tend to eat in response to external factors like parties and celebrations, have fewer problems with their weight loss than those who eat in response to internal factors such as emotions. The study also found that emotional eating was associated with weight regain in people who had successfully lost weight

The researchers analyzed individual’s responses to questions in a well-known research tool called the Eating Inventory which is designed to assess three aspects of eating behavior:

- Cognitive restraint

- Hunger

- Disinhibition

The main focus was on the third item, since some previous research has suggested that disinhibition as a whole is an accurate predictor of weight loss.

The disinhibition scale evaluates impulsive eating in response to emotional, cognitive, or social cues.

There were two groups in the study. The first consisted of 286 overweight men and women who were currently participating in a behavioral weight loss program. The second group included 3,345 members of the National Weight Control Registry (NWCR), an ongoing study of adults who have lost at least 30 pounds and kept it off for at least one year.

The investigators found that the components within the disinhibition scale could be grouped into two distinct factors: external and internal disinhibition.

An example of external disinhibition would be the person who overeats when they are with someone who is also overeating, or the person who just overeats at a party, picnic or celebration.

The person with internal disinhibition eats in response to thoughts and feelings such as loneliness, upset or anxiety.

In both groups internal disinhibition was a significant predictor of weight over time. For participants in the weight loss program, the higher the level of internal disinhibition, the less weight an individual lost over time. The same was true for maintainers in the NWCR: Internal disinhibition predicted weight regain over the first year of registry membership.

Before starting a weight management program it is very helpful to know which group you are in. It provides us with a quick and easy method of tailoring the program to the individual, and tells us where to put our efforts.

Sleep Deprivation and Emotional Instability

Most of the time we are in control of our moods, rather than our moods being in control of us. One of the main things that we learn as we get older is not simply to damp down our emotional reactions, but to make them “contextually relevant:” we produce the right emotional response for the right situation. Yet we also know that there are exceptions: times when our emotions over-run any attempts at our control.

Second, we all know that sleep deprivation can be a Bad Thing. It is known to impair a range of mental and physical activities, including immune function, metabolic control and many cognitive processes, including learning and memory.

It has long been suspected that sleep deprivation can have significant effect on mood. Many of us feel irritable and distractible if we haven’t slept enough, and you may have had the experience of being up all night and feeling a little bit “high” in the morning. It has also been known for centuries that mood disorders are very commonly associated with sleep disturbances, and sleep disturbance is often the first sign that someone with mood problems is running into trouble. So mood and sleep must be linked in some way.

Despite these common observations, there has never been that much empirical evidence for the impact of sleep deprivation on mood, and in particular the effects of sleep deprivation on the brain.

An important new study by researchers from Harvard Medical School and the University of California at Berkeley has just been published in the journal Current Biology, and it is beginning to fill in some of the gaps in our knowledge.

The amygdala is known to be involved in processing of emotionally salient information, particularly unpleasant or aversive stimuli. In mature individuals, the emotional centers of the brain are usually controlled and modulated by an array of connected systems, mainly in the frontal regions of the brain. One particularly important part of the frontal lobes that is involved in controlling the amygdala is the medial-prefrontal cortex (MPFC). Under normal conditions the MPFC is supposed to exert an inhibitory, top-down control of the amygdala, so that we only generate appropriate emotional responses.

The scientists worked with 35 volunteers who were deprived of sleep for 35 hours. Blood flow can be used to deduce which specific regions of the brain are active. The researchers used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to examine the blood flow – and therefore activity – in the brains of the volunteers in real time, both during and after sleep deprivation.

After going without sleep, the participants were asked to look at images that were designed to trigger angry or sad emotional responses. The investigators discovered that the amygdala showed 60% higher reactions to the images compared with people who are not sleep-deprived.

This is an extraordinarily large effect and implies that sleep deprivation knocks out the normal control mechanisms in the frontal lobes so that the sleep-deprived brain reverts to a more primitive pattern of activity. As a result we become unable to put emotional experiences into context and produce controlled, appropriate responses.

If we needed any more reasons to get a good night’s sleep, this one is very powerful. It also re-iterates something very important: if you or a loved one have had problems with mood, anger or anxiety, it is essential to watch your sleep pattern. Any change may be a harbinger or trouble, and is an excellent early warning that you or they need a hand to make sure that things stay on an even keel.

“Your brain shall be your servant instead of your master, you will rule it instead of allowing it to rule you.”

–Charles E. Popplestone (American Author of Every Man a Winner, 1936)

“Control your emotions or they will control you”

–Chinese Proverb

“For the uncontrolled there is no wisdom, nor for the uncontrolled is there the power of concentration; and for him without concentration there is no peace. And for the unpeaceful, how can there be happiness?”

–Bhagavad Gita (Ancient and Sacred Sanskrit Poem Incorporated into the Mahabharata)

“He who controls others may be powerful, but he who has mastered himself is mightier still.”

–Lao Tzu (Obscure Chinese Philosopher, Founder of Taoism and Alleged Author of the Tao-Te Ching, c. 604-c. 531 B.C.E.)

“ . . . let every man be swift to hear, slow to speak, slow to wrath.”

–The Bible, James 1:19

“When angry, count ten before you speak; if very angry, a hundred.”

–Thomas Jefferson (American Writer, Philosopher, Politician and, from 1801-1809, 3rd President of the United States, 1743-1826)

Emotion and Cancer Survival

There is some research coming out in the December issue of the journal Cancer from some researchers at the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine and other colleagues. The results surprised me, particular since I know some of the authors, and they are first rate investigators.

For over thirty years, most research studies have claimed to find an association between emotions, attitudes and beliefs, and the chance of survival form several types of cancer. Entire psychological wellness and psychotherapy programs have been designed around that premise.

The study suggests that emotional wellbeing has no effect on the chances of surviving head and neck cancer. People with negative emotions had the same survival rate as people with positive emotions.

Patients from two Radiation Therapy Oncology Group clinical trials completed a quality of life questionnaire known as the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General (FACT-G) at the start of the trials. So these assessments were added on to studies of different cancer treatments. One trial was looking at what is known as “dose fractionation strategies” and the other was looking at combined chemotherapy and radiation treatments.

The FACT-G questionnaire included a collection of items called the Emotional Wellbeing Scale. This was assessed against overall survival.

There were 1,093 at the start of the trials, of whom 646 died during the period of the study. One of the reasons for trusting the data is that this large sample together with the consistency in the treatment the patients received have made this study one of the most statistically robust ever conducted.

Emotional state did not predict survival, and the results did not change when the researchers took into account possible effects such as interactions between emotional wellbeing and the methods of the study, gender, the primary site of the cancer, or the stage of the cancer.

There are several important points:

- The study only included head and neck cancer patients. These are often very traumatic cancers, but they do not usually involve the endocrine system. Some of the best data on emotions and survival come from studies of breast cancer, which often involves disturbances of hormones that may themselves have an impact on mood and survival. And mood can have a big impact on hormones

- The patients in the study had to keep coming to appointments, and to follow instructions, so they may not be representative of all people with head and neck cancer

But the most important thing is this: before critics jump off the deep end, let’s be very clear.

The study is not saying that having an optimistic or positive emotional outlook does not bring benefits to cancer patients. All it is saying is there is no evidence that it prolongs life.

Psychotherapy, art therapy, bibliotherapy and many others can all provide a great many emotional and social benefits.

They may not add anything to the years that a persons lives, but they may add greatly to the life in those years.

Chocolate, Comfort Foods and Depression

Most people have done a bit of comfort eating from time to time: candies and chocolates are usually the favorites. That’s not a coincidence. Not only do they taste good, but chocolate also contains chemicals that may improve mood, and sugar can have an indirect impact on the uptake of specific amino acids into the brain, where they go on to form the chemical neurotransmitters involved in inter-cellular communication and learning.

On the more serious side, some types of mood disorders, particularly seasonal affective disorder, premenstrual syndrome and the so-called “atypical depression” are often associated with quite sever cravings for chocolate.

So I was very interested to see a paper from colleagues in Australia in this month’s issue of the British Journal of Psychiatry.

Gordon Parker and Joanna Crawford examined links between chocolate craving in people who are depressed and both personality style and atypical depressive symptoms, with a web-based questionnaire completed by nearly 3000 individuals reporting clinical depression.

People accessing a mood disorder consumer information website (http://www.blackdoginstitute.org.au) were invited to participate in an online survey of lifetime treatments for a depressive episode, together with some interesting evaluation tools.

Half of the respondents said that they craved chocolate, and the number was slightly higher in women. They said that they felt that chocolate helped with depression, anxiety and irritability. The ones who said that chocolate helped were more likely to score higher on a “neuroticism” scale, particularly irritability and rejection sensitivity.

Five years ago the same team found that atypical depression was associated with a personality that was especially sensitive to rejection, and also tended to be linked with several symptoms – including food cravings – that tie in with behaviors aimed to try and make us feel better and to maintain internal balance.

The results suggest that people with certain personality styles derive personal benefit from comfort eating. Some research has linked carbohydrate craving to the opioid system in the brain, and it is possible that munching on chocolate may be an example of genuine self-medication. People eat to chocolate to calm down their ability to feel emotional distress.

The trouble is, of course, that although chocolate is yummy and may even be therapeutic, too much can be a bad thing. Weight problems are common in people with chronic depression, especially the “atypical” type.

“Chocolate causes certain endocrine glands to secrete hormones that affect your feelings and behavior by making you happy. Therefore, it counteracts depression, in turn reducing the stress of depression. Your stress-free life helps you maintain a youthful disposition, both physically and mentally. So, eat lots of chocolate!”

–Elaine Sherman (American Culinary Expert, Teacher and Writer, 1938-2001)

“Look, there’s no metaphysics on earth like chocolates.”

–Fernando Pessoa (Portuguese Poet, 1888-1935)

Memory and Emotion

Your humble reporter has had more than his fair share of major life events. As a sixteen year old I was a passenger in car that had a meeting with another vehicle driving down the wrong side of the road. This was in England, where folk always do drive on the “wrong” side, but the fellow who was kind enough to arrange the collision could never explain why he was driving on the “American” side.

The interesting thing is that the memory of the crash is seared into my memory: I can remember the license plate of the vehicle that hit us. Some people call that a “flashbulb memory.”

If you live in the United States you probably have clear and fairly accurate memories of where you were and what you were doing on September 11th 2001.

This kind of experience is not uncommon: most of us have noticed that events that occur during heightened states of emotional arousal, such as fear, anger, happiness and sex are far more memorable than less dramatic occurrences. The emotional “load” of an event is a key factor in remembering it. Previous studies have confirmed that heightened states of emotion can facilitate learning and memory.

This makes good evolutionary sense: emotionally charged events are likely to be the ones that we need to remember. From an evolutionary perspective, it is more important to remember where Mr. Saber-tooth Tiger lives, rather than the names of the Kings and Queens of England.

Therefore the regions of the brain that are responsible for the storage of memories need to distinguish between important experiences and those that less significant for survival. The brain must have some mechanisms for giving priority to emotionally charged memories, so that they are converted and stored in long-term memory.

The downside is that in some situations, for instance posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), this process can become pathological and people can be tormented by persistent vivid memories of traumatic events.

Writing in the journal Cell, researchers from Johns Hopkins University and their collaborators at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory and New York University may have identified the biological basis for this phenomenon. Memories in the brain are held in neurological circuits and each new experience creates a new circuit. The investigators have found that the hormone norepinephrine, which is released during emotional arousal, serves to “prime” nerve cells to remember events. They do this by increasing the neurons’ chemical sensitivity at the precise sites where nerves rewire to form new memory circuits.

Norepinephrine is often described as one of the “fight or flight” hormones and it is likely also involved in the third type of response to a threat, which is “freeze.” In the brain norepinephrine energizes the circuit-building process by adding phosphate molecules to a nerve cell receptor called GluR1. The phosphates help guide the receptors to insert themselves next to a synapse.

So when the emotionally-charged brain needs to form a memory, the nerves have plenty of available receptors to quickly adjust the strength of the connection and lock that memory into place.

The researchers targeted the GluR1 receptor after discovering that if it is disrupted in mice, the little creatures develop spatial memory defects. They tested the idea by either injecting healthy mice with adrenaline or exposing them to fox urine, both of which increase norepinephrine levels in the brain.

They then analyzed the brains of the mice and found increased phosphates on the GluR1 receptors and an increased ability of these receptors to be recruited to synapses.

When the researchers put mice in a cage, gave a mild shock, took them out of that cage and put them back in it the next day, mice who had received adrenaline or fox urine were likely to “freeze” in fear, compared with mice who had not been exposed to the adrenaline or fox pee. This implies an enhancement of their memory of the cage and its unpleasant associations.

In a similar experiment with mice genetically engineered to have a defective GluR1 receptor, adrenaline injections had no effect on mouse memory. So this provides us with further evidence of the “priming” effect of norepinephrine on the receptor.

There has been a lot of recent interest in using medications like beta-adrenoreceptor blocker propranolol – which prevents some of the actions of norepinephrine – to prevent the development of PTSD in people who have been exposed to extreme trauma, and this research may provide the scientific basis for this kind of therapy.

On the other hand, this research leads me to predict that people with overactive GluR1 receptors may be constantly curious about their environment, but also likely to be chronically anxious and more likely to develop PTSD.

We have known for years that propranolol and other beta-blockers may attenuate some of the physical symptoms associated with anxiety. Most people had assumed that the medicine worked by reducing heart rate, shaking and sweating. But experienced clinicians usually find that beta blockers that cross the blood/brain barrier work best, and it may well be that these drugs also have direct actions in the brain itself.

“Recollection is the only paradise from which we cannot be turned out.”

–John Paul (a.k.a. Johann Paul Friedrich Richter, German Novelist and Humorist, 1763-1825)

“The existence of forgetting has never been proved: We only know that some things don’t come to mind when we want them.”

–Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (German Philosopher, 1844-1900)

“The moment we find the reason behind an emotion … the wall is breached, and the positive memories it has kept from us return too. That’s why it pays to ask those painful questions. The answers can set you free.”

–Gloria Steinem (American Feminist, Political Activist and Editor, 1934-)

Emotions and Recovery from Hip Surgery

A patient’s emotional state plays a significant role in his or her recovery from hip surgery according to research from Saint Louis University. This research was particularly interesting because the researchers were not looking for a link.

Orthopedic surgeons typically use two tests to determine if a patient has recovered from hip surgery: one is a clinical measure of hip function and the second is a patient questionnaire that looks at a number of factors that may play a role in the overall success of the surgical procedure. Originally the research was simply designed to see if the two measures, the clinical one that has been in use for decades, the other, a new subjective scale, correlated in some way.

The clinical test found good-to-excellent results, while the self-test taken by the same patients showed significantly worse recovery. The disparity could be explained by a section of questions on the self-test that are not addressed by the clinical test: those dealing with emotional well-being. After post-operative mobility, the patient’s emotional status was the most important factor in determining how well he or she thought recovery was going.

It is common for doctors to think that patients are doing well because they have achieved a good technical result. But if the patient is still miserable, depressed and in pain, we should not congratulate ourselves on a job well done.

Yet a great many people are denied the help that they need. For instance they may have already had depression or they may be depressed because of pain and immobility. It does not really matter which came first. If the psychological aspects of the illness or the surgery are not addressed, people are not likely to recover. The same goes for having poor nutrition or poor social supports.

The whole point of Integrated Medicine is to address every aspect of a person: physical, psychological, social, subtle and spiritual.

This study provides further evidence that if we only look at the physical aspects of a problem or an intervention, we are going to miss the boat.