Memory is a Key to Visualization

Most of us have been told something about the potential benefits of visualizing an outcome, and I know from working with many athletes, chess players, dancers and even surgeons, that most are very good at visualizing exactly what they want and where they are going to be.

I have recently talked about the ways in which encoding of memory for faces and the crucial role of memory in creating images of the future.

There is some important confirmatory research from the Wellcome Trust Centre for Neuroimaging, University College in London. A study led by Dr Eleanor Maguire has just been published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. It involved five participants with dense amnesia caused by damage to the hippocampus on both sides of the brain.

The researchers asked the participants – and a control group without amnesia – to imagine several future scenarios, such as visiting a beach, a museum and a castle, and then to describe what the experience would be like. They then analyzed the subjects’ comments sentence by sentence, scoring each statement based on whether it involved references to spatial relationships, emotions or specific objects.

All but one of the people with amnesia were worse at imagining future events than people with normal memory. Their visualizations of future events were more likely to be disorganized and lacking in emotion.

Here is a quotation from one of the subjects:"It’s not very real. It’s just not happening. My imagination isn’t…well, I’m not imagining it, let’s put it that way."

The hippocampus does not simply relive past experiences, it also supports our ability to imagine any kind of experience including possible future events.

This is yet more evidence against the idea that memory works like a kind of video camera, passively recording your life. It is a far more dynamic process that include your own beliefs, emotions and expectations.

“A rock-pile ceases to be a rock-pile the moment a single man contemplates it, bearing within him the image of a cathedral.”

–Antoine de Saint-Exupéry (French Aviator and Writer, 1900-1944)

“All acts performed in the world begin in the imagination.”

–Barbara Grizzuti Harrison (Italian-America Journalist, Essayist and Author, 1934-2002)

“I visualize things in my mind before I have to do them. It’s like having a mental workshop.”

–Jack Youngblood (American Football Player and Member of the Pro Football Hall of Fame, 1950-)

Memes and Magical Thinking

There were so many excellent papers at this year’s British Association Festival of Science, that I still haven’t had been able to comment on all of them, but here’s another one that I found interesting for two reasons.

Bruce Hood, who is Professor of Experimental Psychology at the University of Bristol, presented an interesting paper on the near-Universality of superstitious beliefs and magical thinking. In his view people are naturally biased to accept a role for the irrational, and magical thinking is hard-wired into our brains.

Magical thinking is invaluable to an artist: being able to make new connections is the key to their creations. But it has long been argued that either rejecting or accepting magical thinking may both be potential triggers of psychopathology. I once treated a young Israeli man who, during the first Gulf War, became convinced that Saddam Hussein was personally writing the Israeli man’s name on each Scud missile. He refused to remove his gas mask, and eventually his thinking became delusional.

Bruce’s conclusion is that magical thinking and a belief in the supernatural is an evolutionary adaptation. He goes on to argue that the rabid atheists who blame organized religion for the spread “illogical thinking” and a belief in the supernatural and are just plain wrong. Instead he contends that religion may capitalize on a natural bias to assume the existence of supernatural forces.

In a world in which religious fundamentalism is something of a challenge, he had this to say:

“It is pointless to get people to abandon their belief systems because they operate at such a fundamental level that no amount of rational evidence or counter evidence is going to be taken on board to get people to abandon these ideas.”

Bruce has carried out studies to show how the brains of even young babies organize sensory information. They supply what is missing and use the information to generate theories about the world.

In adulthood, the visual centers of the brain still fill in details that are not there, as shown in common visual illusions such as the blind spot. Several years ago we did some experimental work on facial recognition, and it is remarkable how little information is needed to recognize a face: the brain supplies the missing pieces of the picture. This childhood “intuitive reasoning” persists in to adulthood and may explain many aspects of adult magical beliefs. We are programmed to see coincidences as significant and to attribute minds to inanimate objects.

One form of this is known as pareidolia in which vague and random stimuli are misperceived as recognizable patterns. Examples of this are seeing shapes in clouds or in a fire. With the new information from the European Space Agency, perhaps we could include seeing the Face on Mars.

Professor Hood used an interesting example. He offered members of the audience the chance to wear a sweater, for which he would pay them a sum of money. They were all happy to do so, until they heard that it had supposedly belonged to a mass murderer, when suddenly there were no takers. Many said that they felt that the clothing was contaminated with evil.

But I don’t think that Bruce has taken something else into account. According to the theory of spiral dynamics, we are all mixtures of Memes. We tend to associate magical thinking with the Purple Meme. It would be very valuable to look at a person’s developmental level and to see how much he or she engages in magical thinking. Someone once said to me, “Are you superstitious?” I said, “No, but I do understand that there are many forces at work in the Universe, and we do not yet know all of them.”

Are you a magical thinker, or is it that you are aware of the unseen forces of the Universe?

“The universe is full of magical things, patiently waiting for our wits to grow sharper.” –Eden Philpotts (Indian-born English Novelist, Dramatist and Poet, 1862-1960)

Quantum Mechanics and Zen Koans

I have talked before about the ways in which some people abuse and misuse quantum mechanics.

Since I wrote that article, I’ve had loads of examples sent to me. I’ve also seen lots of books that are often pretty good.

Except for the quantum fig leaf that they use to provide authority and support for what the author is saying.

Even for highly gifted mathematicians – and I’ve known many – understanding quantum mechanics can be a bear. Remember that Einstein himself was unconvinced by the theory, and he was not just a gifted mathematician, but a superbly creative individual who could visualize like no-one else.

And that was part of his difficulty. One of the problems of popular interpretations of quantum mechanics is that they consist of forced metaphors and comparisons with familiar events rather than actual descriptions. Let me take an example: In a quantum system a particle following two different paths at the same time, while not being observed. For most people that sounds like a Zen Koan.

Because it is completely different from the way in which things work in the real world, it is very difficult to grasp.

Quantum mechanics is something that you have to learn to accept and get used to, rather than trying to imagine it in terms of familiar observations in the macroscopic natural world. Many of the concepts cannot be fully expressed in English. Many of the best science writers are always at pains to tell us that what they are saying is suggestive of the ideas, rather than being a complete description of a mathematical construct. Using written language to describe a phenomenon in the quantum world is a bit like using a tape measure to determine the volume of water in a puddle. You can come up with a rough approximation, but not an accurate number.

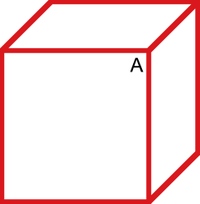

The only way in which you are able to really understand quantum mechanics is with a change in perception. The moment when people “see it” for the first time, it’s a bit like looking at a Necker cube:

If you look at the corner that I’ve marked “A,” is it pointing toward you or away from you?

Most people see it one way and then if they stare for a moment, it will “flip” it will look the other way.

It’s a simple visual illusion, but it demonstrated the perceptual shift that you need to really understand quantum mechanics. It requires you to be able to think in a completely new way, and very few people have been able to do that.

This is really what the Danish Physicist and Nobel Laureate Niels Bohr meant when he made the famous comment, “Your theory is crazy, but it’s not crazy enough to be true.”