You Know You’re Getting Older When…

“You know you’re getting older when your supply of brain cells is finally down to a manageable size.”

“You know you’re getting older when you can live without sex but not without glasses.”

“You know you’re getting older when you begin every other sentence with, “Nowadays…”

“You know you’re getting older when the pharmacist has become your new best friend.”

“You know you’re getting older when you sing along with the elevator music.”

“You know you’re getting older when you look for your glasses for half-an-hour, then find they’ve been on your head all the time.”

“You know you’re getting older when the twinkle in your eye is only the reflection of the sun on your bifocals.”

“You know you’re getting older when you finally got your head together, now your body is falling apart.”

“You know you’re getting older when you read more and remember less.”

“You know you’re getting older when your investment in health insurance is finally beginning to pay off.”

Antioxidants May Raise Cancer Risk?

Regular readers will know that I have for some years now been raising a red flag the wholesale promotion of antioxidants.

The trouble is this: antioxidants are supposed to help rid us of some of the free radicals that have been implicated in a small number of diseases, and may also play a role in some of the physical aspects of aging. However, free radicals are also some of the major cancer killers in the body, so eradicating them – even if it were possible – hardly seems like a good idea.

According to an analysis of a dozen studies including more than 100,000 patients in the Mayo Clinic Proceedings taking antioxidant supplements do not reduce cancer risk.

In fact smokers who take beta carotene supplements could be increasing their risk of smoking-related cancer and death.

Different antioxidants have different effects, and their effects may also vary depending on the part of the body involved.

The researchers looked at 12 trials that compared antioxidant supplements with placebo on cancer incidence and mortality. Antioxidant supplements did not reduce the risk of cancer. When they looked separately at beta carotene, they found the nutrient actually increased cancer risk by 10 percent among smokers. There was also a trend toward a greater risk of dying from cancer with beta carotene supplementation.

Selenium supplements reduced cancer risk by 23 percent among men, the researchers found, but had no effect on women. While vitamin E had no anti-cancer effect overall, supplementation with the nutrient was tied to a 13 percent lower prostate cancer risk.

A large study looking at vitamin E supplementation for prostate cancer is currently underway. While future studies of beta carotene and vitamin E for cancer prevention are very unlikely to show effectiveness, it would be worth doing further studies on selenium.

The moral of the story: we should be going for a balanced diet and a balanced life in general rather than putting our hopes in an over-simplified nutritional message.

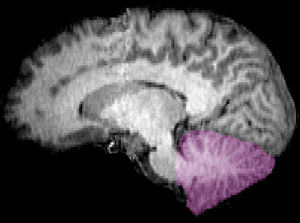

Mature Plasticity in the Human Brain

The more we look, the more we understand that the human brain retains a remarkable ability to learn and re-fashion itself well into old age. The old idea that young brains are flexible, but that age causes us to become “hard-wired” and inflexible is not correct.

This has been confirmed in some new research that has just been published in the journal Neuron by investigators from Johns Hopkins who have shown that adult neurons are not glued in place as rigidly as had been thought.

The investigators led by David Linden used a new technique known as two-photon microscopy that allowed them to living neurons at work in the intact brain. The researchers injected fluorescent dye into the brains of mice to illuminate a subset of neurons and then viewed these neurons through a window in the skull of living, anesthetized mice.

They examined neurons that extend axons to the cerebellum, a region of the brain involved in coordinating motor and sensory information. These axons have a primary trunk that runs upward and several smaller branches that sprout out to the sides.

While the main trunk was firmly connected to other target neurons in the cerebellum, the side branches were mobile: Linden describes them like this:

“The side branches swayed like kite tails in the wind.”

Over the course of a few hours, individual side branches would highly dynamic behavior, elongating, retracting and morphing. These side branches also failed to make conventional synaptic connections with adjacent neurons. The motion of the side branches was arrested stalled by a drug that produced strong electrical currents in the axons.

Why the brain would want such motile, non-connected branches remains a mystery.

They may provide a second mechanism for conveying information beyond traditional synapses. Alternatively they may be involved in nerve regeneration.

Whatever the final answer, it is clear that the adult brain remains a remarkably plastic, fluid and flexible structure.

Excellent news for all of us!

“That which is flexible and flowing will prosper and grow. That which is rigid and blocked will wither and die.”

–Tao te Ching

“When a noble life has prepared old age, it is not decay that it reveals, but the first days of immortality.”

–Muriel Spark (Scottish Writer, 1918-)

“You will stay young as long as you learn, form new habits and don’t mind being contradicted.”

–Marie, Baronin von Ebner-Eschenbach (a.k.a. Baroness Marie von Ebner-Eschenbach, Austrian Writer, 1830-1916)

Your Brain's Inertial Navigation System

There are many mysteries about the human brain. One is the role of the cerebellum that lies at the back of your head right underneath the cerebral hemispheres. Most students believe that it is only involved in balance and motor coordination, but that does not make much sense: relative to the rest of the brain, humans have the largest cerebellum of any species apart form the dolphin. And there are good reasons for believing that it is involved in the coordination of emotional and social processes, as well as language.

We now learn that it may have yet another function. Colleagues from Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis report that there is a sophisticated neural computer that is buried deep in the cerebellum, that performs inertial navigation calculations to calculate our precise movement through space.

These calculations are incredibly complex and involve the vestibular system in the inner ear that provides the primary source of input to the brain about the body’s movement and orientation in space. However, the vestibular sensors in the inner ear only give us information about the position of our head position. In addition the vestibular system’s detection of head acceleration cannot distinguish between the effect of movement and that of gravitational force.

Dora Angelaki and her team based their brain studies on the predictions of a theoretical mathematical model. The model proposed that the brain could calculate inertial motion by combining two things:

1. Rotational signals from the semicircular canal in the inner ear with

2. Gravity

Based on previous research, they concentrated their search for the brain’s inertial navigation system on particular types of neurons called Purkinje cells, in a region of the cerebellum known to receive signals from the vestibular system. This region is known as the posterior cerebellar vermis, a narrow, worm-like structure between the brain’s hemispheres. It has been known for two centuries that damage to the cerebellar vermis can produce bizarre neurological problems.

In their experiments, the researchers measured the electrical activity of these Purkinje cells in monkeys as the animals’ heads were maneuvered through a precise series of rotations and accelerations. After analyzing the electrical signals measured from the Purkinje cells during these movements, the researchers concluded that the specialized Purkinje cells were, as predicted, computing earth-referenced motion from head-centered vestibular information.

This is a remarkable finding: the cells are able to make complex deductions based on very little information.

Cells in the brain, particularly cells of the Purkinje type are designed to adapt and learn. So the finding gives yet more credence to the idea that balance, coordination and orientation in space are learnable skills. That will be the topic of another research project.

But for now, the evidence suggests that anything that helps you to practice these skills will likely pay dividends as you get older.

Zen and the Aging Brain

The two main kinds of meditation that have received a lot of research attention are Zen and Transcendental Meditation. Both produce measurable physiological changes and both may produce changes in the brain.

Zen meditation is centered on attentional and postural self-regulation.

As we age, there is normally some decline of cerebral gray matter volume and attentional performance. As I have pointed out, those changes do not necessarily mean a decline in functioning, but simply a change.

In a new study researchers here in Atlanta examined how the regular practice of meditation might affect the brain. The researchers studied 13 regular practitioners of Zen meditation and 13 matched controls.

They used some sophisticated techniques to calculate the volumes of different regions of the brain. They also performed a computerized sustained attention task.

While the control subjects showed the expected negative correlation of both gray matter volume and attentional performance with age, the meditators did not show a significant correlation of either measure with age.

Interestingly, the effect of meditation on gray matter volume was most prominent in a region of the brain called the putamen, a system of the brain that is strongly implicated in attentional processing.

These findings are intriguing and are consistent with some of the research done in Richard Davidson’s laboratory in Wisconsin, that looked at people practicing a different form of meditation, but also showed that expert meditators produce both structural and functional changes in their brains.

The study on aging suggests that the regular practice of meditation may have neuroprotective effects and reduce the cognitive decline associated with normal aging.

If that is confirmed, I think that we have something else to add to our list of “things to do to reduce your risk of getting Alzheimer’s.”

Brain Training and the Paradox of Aging

For centuries, people in cultures throughout the world have believed that increasing age is associated with increasing wisdom. Not just knowledge and experience, but wisdom. Is this an old wives’ tale, or is there something to it?

There is growing evidence that as we age our brains actually become stronger. Everyone missed it, because the emphasis was on memory, concentration and thinking speed, and those may all deteriorate with age. What changes is that as we age we become more efficient at making associations rather than thinking linearly. we also recruit regions of the brain that may have lain dormant for years. At the same time, different types of mental training, including meditation, can improve many aspects of our cognitive abilities, and may also enrich and even grow appropriate regions of the brain.

Some new data from a study being conducted at Wake Forest University Baptist Medical Center in North Carolina suggests that it is possible to use a fitness program for your brain that can improve thinking skills, attention and concentration as reliably as lifting weights can increase muscle strength.

Preliminary findings from the study, which used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to record brain activity, were presented last week at the Organization for Human Brain Mapping conference in Chicago.

As we age, we do experience changes in how we perceive the information that our senses gather from the environment. As I mentioned older adults combine information from the different senses more readily than do younger adults. This is known as sensory integration, and the down side is that it can lead to difficulties in blocking out distracting sights and sounds while still maintaining focus on important information. You are probably familiar with the “Cocktail Party Phenomenon.” You are in a loud room, but because someone is saying something interesting, you are able to block out uninteresting information. This technical term for this is cortricofugal inhibition. As we get older it gets more difficult to do the inhibiting.

The Brain Fitness in Older Adults (B-fit) study has been designed to establish whether eight hours of brain exercise can improve the ability of healthy older adults, ages 65 to 75 years, to filter out unwanted sights and sounds.

The B-fit study uses fMRI to visualize blood flow and brain activity to determine how attention training affects brain function. The training involves either a structured one-on-one mental work-out program or a group brain exercise program. During the one-on-one sessions, the volunteers were asked to ignore distracting information and tasks get harder as the eight-week training progresses. For the group sessions, participants learn new information relevant to healthy aging and are then tested on their ability to apply the new information.

All participants had an fMRI scan during a distraction task. They had to look for target words or numbers while ignoring distracting sounds. The scans showed brain activity in areas related to both sight and sound. Follow-up fMRIs showed that in the group receiving the one-on-one training, activity related to sight was increased, while activity related to sound was decreased. In addition, performance on the task was improved.

So the data do indeed suggest that attention training is a way to reduce

older adults’ susceptibility to distracting stimuli and therefore help improve

concentration.

And what about wisdom?

I have written in Healing, Meaning and Purpose that “Wisdom is the integration of understanding:” making more new associations and drawing conclusions based on a new perspective is a gift of aging. The training enables us to make sense of and communicate our conclusions.

When it comes to the brain, use it or lose!

Successful Aging

One of the most promising changes in psychology is the ever-greater emphasis on what makes us healthy, rather than constantly looking at the things that make us sick. There is an important approach called Behavioral Activation (BA) Theory, which emphasizes environmental and behavioral factors as determinants of our overall well-being. According to the theory, reduced engagement in pleasurable activities may be an important precursor of reduced well-being. This makes good sense: it is estimated that as much as 90% of our higher cortical functions are designed for social interactions.

This is something that I wrote in Healing, Meaning and Purpose:

“Nothing in the Universe exists in isolation: We live in a Universe of relationships. It is inconceivable that anything can exist except in relationship to something else. The entire Universe is made up of integrated systems that function, develop and evolve together. A failure to construct and maintain healthy relationships can be a cause of much distress.

Several years ago I reported some interesting observations. At the time, I was doing a lot of research on diseases of blood vessels. I had developed a laboratory method for taking some of the cells that line blood vessels from volunteers and then growing them in a cell culture dish. We discovered that if we did not have enough cells in the dish, they would all die of “loneliness.” The exception is cancer cells, which in culture will grow on their own, like weeds.”

As an example in a paper published in February in the Archives of General Psychiatry it was shown that lonely individuals may be twice as likely to develop the type of dementia linked to Alzheimer’s disease in late life as those who are not lonely. The theory has been shown to predict psychiatric well-being in a number of populations, including the caregivers of people with Alzheimer’s disease, people with chronic pain, cancer patients and community-dwelling older people.

It is also known that psychiatric well-being, particularly emotional well-being, may play an important role in cardiovascular health. This may be due to an increase in the activity of the sympathetic nervous system that increases not only blood pressure, but also the levels of inflammatory mediators and coagulant factors in the blood.

In research from the University of California at La Jolla that was presented on Monday at the 2007 Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association in San Diego, California, twenty two people with a mean age of 70 were studied, to see if there was a link between their behavioral activation, i.e. how satisfied they were with their leisure activities, their affective well-being and their blood pressure.

The findings were as expected: the less satisfied and engaged people were, the higher was their blood pressure.

This is only preliminary data, but it confirms something that we have said before: as we get older it is as important to stay socially engaged as it is to do mental exercise.

And if you known someone who is older and isolated, you might want to go and see them.

“The most terrible poverty is loneliness and the feeling of being unloved.”

–Mother Teresa of Calcutta (Albanian-born Indian Nun, Humanitarian and, in 1979, Winner of the Nobel Peace Prize, 1910-1997)

“What makes loneliness an anguish is not that I have no one to share my burden, but this: I have only my own burden to bear.”

–Dag Hammarskjöld (Swedish Statesman, Secretary-General of the United Nations from 1953-1961, and, in 1961, Winner of the Nobel Peace Prize, 1905-1961)

Attachment and Well-Being In the Elderly

Attachment theory is a psychological concept that was developed by John Bowlby in Britain and Harry Harlow

in the United States in the late 1950s. The idea is that humans and

many other animals have evolved an adaptive tendency to maintain

proximity to an attachment figure.

Attachment is defined as an emotional bond that one person forms

between himself or herself and another specific person. Originally the

theory was developed to explain the relationship of a parent and child,

but over tie it has become realized that attachments can occur

throughout life, and if they become abnormal, they can lead to

loneliness, isolation and psychopathology. There has recently been a resurgence of interest in attachment styles, and how they interact with emotional and behavioral expression during the development of dementia.

There was some interesting research presented today at the 2007 Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association

in San Diego, California. Investigators from Charlottesville, Virginia

looked at 39 older patients (27 were women): 49% were aged between 65

and 74 and the remainder was over 74.

- 41% of women and 33% of the men said that their activities were limited by physical and/or emotional problems

- 41% of the women and 17% of the men endorsed at least two out of three indicators of depression

- When they examined their attachment styles, 28% were secure, 59% avoidant and 13% enmeshed

- An avoidant attachment pattern is more common among the elderly than it is among younger people

- Understanding attachment style could be very helpful in

understanding how people react to their healthcare providers and their

preferred coping styles

For anyone working or living with elderly people, attachment theory

is well worth investigating. There is already some preliminary evidence

that specific interventions may help older people with avoidant

attachments.

Genes, Culture and Aging

The study of genetics is becoming ever more interesting. Not only have we gone well beyond the nature/nurture debate, but also there is more and more interest in genetic influences on culture and vice versa: the way in which culture impacts gene expression. It is also clear that our brains are amazingly plastic: nutrition, emotional environment, education and experience all impact brain development.

Now it appears that culture does indeed affect the brain.

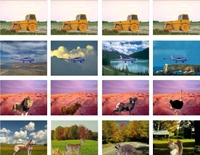

Westerners and East Asian people process visual information differently: Westerners preferentially process objects, while Asians tend to pay more attention to contextual information. In studies of semantic organization, Asians associate pictures based on functional relationships, for instance grouping together a mother and her child based on maternal relationship. Westerners based their associations on physical features and categorical membership, such as grouping together a woman and a man because they are adults. These differences may be changing as young people in Asian cultures are becoming more westernized.

New research has found that the aging brain reflects cultural differences in the way that it processes visual information. This study “Age and culture modulate object processing and object-scene binding in the ventral visual area” is published this month in the journal Cognitive, Affective & Behavioral Neuroscience. This paper (which can be downloaded here) and another published by the same group in 2006 are the first to demonstrate that culture can alter the brain’s perceptive mechanisms.

The research is the result of a collaboration between Denise Park’s group from the University of Illinois and Michael W. Chee, of the Cognitive Neuroscience Laboratory, SingHealth, in Singapore. The researchers conducted an array of cognitive tests on study subjects at their facilities in the U.S. and Singapore, and used identical functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) scanners at both sites. Their analysis involved 37 young and old East Asians, and 38 young and old Westerners. They found significant cultural differences in how the older adults’ brains responded to visual stimuli.

As Professor Park said,

“These are the first studies to show that culture is sculpting the brain. The effect is seen not so much in structural changes, but at the level of perception.”

We have known for decades that East Asians and Westerners process visual information differently. A paper in 1972 reported that East Asians are more likely to pay attention to the context and relationships in a picture than are Westerners, who more often notice physical features or groupings of similar subjects.

More recent research, which analyzed the eye movements of East Asians and Westerners viewing identical images, found that Westerners were more attentive to central, or dominant, objects, while East Asians paid more attention to the background, or scene.

Last year the team reported differing patterns of neural activation in the brains of East Asians and Americans shown identical pictures. The Americans showed more activity in brain regions associated with object processing than the East Asians, whose brains showed more activity in areas involved in processing background information.

The new study takes this work further, comparing neural responses to visual stimuli in young and old adults in both cultures. These are some of the pictures they used in the experimenets:

The researchers found that all four groups – young and old East Asians; young and old Americans – processed background information in part of the brain called the parahippocampal gyrus: a region that is vital to memory encoding and retrieval. As expected, older adults in both cultures had less ability to use “binding mechanisms” – the ability to connect a particular object to its background – in the hippocampus. The older people also had diminished object processing in the lateral occipital cortex.

The most striking finding was that the “object areas” of the brains of older East Asian subjects responded much more weakly to novel stimuli than did those same brain regions in the older Americans. For the older East Asians, a lifetime of attention to the backgrounds, or context, of pictures eventually showed up as a diminished response in the part of the brain that keeps track of foreground objects.

One of the best ways of keeping the brain healthy is with cognitive cross training: doing things like crossword puzzles, but also doing things that exercise other cognitive muscles, like playing the piano. This research would suggest that the exact strategies that we should use will be different in native-born Asian and western-born people. Something to factor in the next time that we get some advice about how to keep the brain young for as long as possible.

Blueberries and Colon Cancer

I have been delighted to see how many people have read and downloaded my Twelve Tips to Reduce Your Risk of Colon Cancer.

There is some new research that was just presented at the shows tha there is a compound in blueberries called pterostilbene that may help protect against the development of colon cancer.

Researchers from Rutgers University and the US Department of Agriculture presented their findings at the meeting of the American Chemical Society in Chicago.

Pterostilbene is a natural antioxidant that mops up free radicals that may, in excess, trigger the growth of some cancers. Similar antioxidants have already been identified in grapes and red wine. Work in mice suggests that pterostilbene may also lower cholesterol levels. The compound also reduced inflammation and the rate of cell division in the bowel both of which are considered to be cancer risk factors.

Pterostilbene is also found in cranberries, sparkleberries, lingonberries and grapes.

It is an extremely good idea to add blueberries to your diet. Do not overdo it! I worry when people extol the virtues of some super-food or super-drink that is supposed to abolish all of your free radicals. Despite the claims of at least one medical correspondent on Fox New, there is usually no evidence that they do so. And in any case, you do not want to abolish all your free radicals: they are key cancer killers.

You want to balance and modulate the free radicals in your body, and blueberries, together with four other portions of fruit and vegetables a day are one excellent way of doing so.