Your Brain's Inertial Navigation System

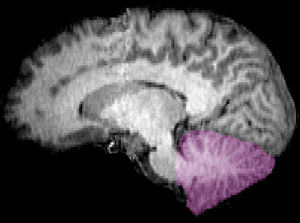

There are many mysteries about the human brain. One is the role of the cerebellum that lies at the back of your head right underneath the cerebral hemispheres. Most students believe that it is only involved in balance and motor coordination, but that does not make much sense: relative to the rest of the brain, humans have the largest cerebellum of any species apart form the dolphin. And there are good reasons for believing that it is involved in the coordination of emotional and social processes, as well as language.

We now learn that it may have yet another function. Colleagues from Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis report that there is a sophisticated neural computer that is buried deep in the cerebellum, that performs inertial navigation calculations to calculate our precise movement through space.

These calculations are incredibly complex and involve the vestibular system in the inner ear that provides the primary source of input to the brain about the body’s movement and orientation in space. However, the vestibular sensors in the inner ear only give us information about the position of our head position. In addition the vestibular system’s detection of head acceleration cannot distinguish between the effect of movement and that of gravitational force.

Dora Angelaki and her team based their brain studies on the predictions of a theoretical mathematical model. The model proposed that the brain could calculate inertial motion by combining two things:

1. Rotational signals from the semicircular canal in the inner ear with

2. Gravity

Based on previous research, they concentrated their search for the brain’s inertial navigation system on particular types of neurons called Purkinje cells, in a region of the cerebellum known to receive signals from the vestibular system. This region is known as the posterior cerebellar vermis, a narrow, worm-like structure between the brain’s hemispheres. It has been known for two centuries that damage to the cerebellar vermis can produce bizarre neurological problems.

In their experiments, the researchers measured the electrical activity of these Purkinje cells in monkeys as the animals’ heads were maneuvered through a precise series of rotations and accelerations. After analyzing the electrical signals measured from the Purkinje cells during these movements, the researchers concluded that the specialized Purkinje cells were, as predicted, computing earth-referenced motion from head-centered vestibular information.

This is a remarkable finding: the cells are able to make complex deductions based on very little information.

Cells in the brain, particularly cells of the Purkinje type are designed to adapt and learn. So the finding gives yet more credence to the idea that balance, coordination and orientation in space are learnable skills. That will be the topic of another research project.

But for now, the evidence suggests that anything that helps you to practice these skills will likely pay dividends as you get older.