Dopamine, Drugs and Diabetes

We recently talked about the increasing evidence that insulin has many extremely important roles in the brain.

New research by investigators at the Center for Molecular Neuroscience and the Institute of Imaging Science at Vanderbilt University Medical Center researchers, working with colleagues in Texas, has found that insulin levels affect the brain’s dopamine systems. These systems are involved in motivation, reward, salience, movement and emotional processing. Disturbances in dopamine pathways have been implicated in substance abuse, as well as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Drugs that interfere with the dopamine pathways may produce Parkinsonism as well as elevations of the hormone prolactin.

The psychostimulant drugs amphetamine and cocaine, as well as related medications for ADHD, block the reuptake of the neurotransmitter dopamine by dopamine transporters (DATs) thereby increasing the level of dopamine signaling. Some of these compounds also cause a massive surge of dopamine through DATs, resulting in high levels of synaptic dopamine that alter attention, increases motor activity and plays an important role in the addictive properties of psychostimulants.

The reason for examining a possible relationship between dopamine and insulin goes back to the 1970s, when it was reported that amphetamine had no effect on diabetic animals and in the 1980s it was shown that diabetic rats did not show the usual stereotyped behaviors when given amphetamine. There were also odd reports about disturbances in the enzyme dopamine-beta-hydroxylase in experimental diabetes and changes in dopamine D1 receptors in the brains of rats with induced diabetes.

These observations lead to this new research into a possible link between insulin signaling and amphetamine action.

They used a standard a rat model of type 1 diabetes in which insulin levels are massively depleted, and then assessed the function of the dopaminergic pathway in the striatum, an area of the brain rich in dopamine.

In the absence of insulin, amphetamine-induced dopamine signaling was disrupted: dopamine release in the striatum was severely impaired and expression of DAT on the surface of the nerve terminal was significantly reduced.

The lack of the DAT protein on the plasma membrane prevents the amphetamine-induced increase in extracellular dopamine, and in turn, amphetamine fails to activate the dopamine pathways that stimulate reward, attention and movement.

The researchers then gave insulin into the brains of the diabetic animals and found that the system returns to normal, indicating that the lack of insulin in the striatum directly affected amphetamine action.

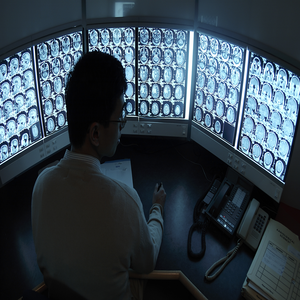

They also developed a probe for brain DAT activity using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). In normal, healthy rats with plenty of insulin, amphetamine increased neural activity in the striatum. But in diabetic animals, activity in the striatum was suppressed.

So there is a powerful interplay between dopamine neurotransmitter systems and insulin signaling mechanisms. The results are some of the first to link insulin levels and dopamine function in the brain and hold several implications for human health and disease.

We need to have another look at the effect of diabetes on the brain. We have known that people with diabetes are at increased risk of cognitive impairment and depression, and we had assumed that it was because of hypoglycemia and vascular disease. Those assumptions may have been wrong.

The findings may also be important for diseases with altered dopamine signaling, such as schizophrenia and ADHD. Insulin may have something to do with the underlying brain disturbances in ADHD. Then control of insulin levels and neuronal responses to the hormone may help determine the efficacy of psychostimulants in people with ADHD.

Every now and then you see people on psychostimulant medications who need huge doses. Perhaps their problem lies with insulin rather than dopamine.