Fear of the Unknown

“Always in big woods, when you leave familiar ground and step off alone to a new place, there will be, along with feelings of curiosity and excitement, a little nagging of dread. It is the ancient fear of the unknown, and it is your bond with the wilderness you are going into. What you are doing is exploring. You are understanding the first experience, not of the place, but of yourself in that place. It is the experience of our essential loneliness, for nobody can discover the world for anybody else. It is only after we have discovered it for ourselves that it becomes common ground, and a common bond, and we cease to be alone.”

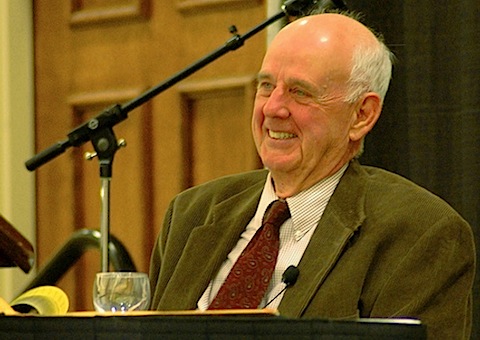

–Wendell Berry (American Poet, Novelist and Essayist, 1934-)

“The Unforeseen Wilderness: Kentucky’s Red River Gorge” (Wendell Berry)

Meditation to Overcome Fear

“Meditation is the only way to overcome fear. There is no other way. Why does meditation help us overcome fear? In meditation we identify ourselves with the vast, with the Absolute. When we are afraid of someone or something, it is because we do not feel that particular person or thing is a part of us. When we have established conscious oneness with the Absolute, with the Infinite Vast, the everything there is part of us. And how can we be afraid of ourselves?”

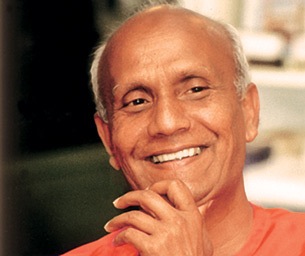

–Sri Chinmoy (a.k.a. Chinmoy Kumar Ghose, Indian Philosopher and Spiritual Teacher, 1931-2007)

Fear Is The Mind-Killer

“I must not fear. Fear is the mind-killer. Fear is the little-death that brings total obliteration. I will face my fear. I will permit it to pass over me and through me. And when it has gone past, I will turn the inner eye to see its path. Where the fear has gone there will be nothing. Only I will remain.”

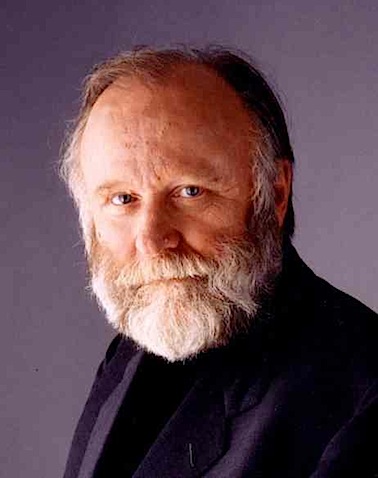

–Frank Herbert (American Writer who Won both Hugo and Nebula Awards for Best Novel, 1920-1986)

Dune: Bene Gesserit Litany Against Fear

“Dune, 40th Anniversary Edition (Dune Chronicles, Book 1)” (Frank Herbert)

Conquer Doubt and Fear

“He who has conquered doubt and fear has conquered failure. Doubt has killed more splendid projects, shattered more ambitious schemes, strangled more effective geniuses, neutralized more superb efforts, blasted more fine intellects, thwarted more splendid ambitions than any other enemy of the human race.”

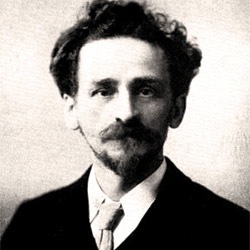

–James Allen (English Mystic and Author, 1864-1912)

Strange Fears

“Men fear silence as they fear solitude, because both give them a glimpse of the terror of life’s nothingness.”

–André Maurois (French Writer, 1885-1967)

Irrational Authority

Some of the big barriers to regaining your Innate Freedom:

“Power on the one side, fear on the other, are always the buttresses on which irrational authority is built.”

–Erich Fromm (German-born American Psychologist and Philosopher, 1900-1980)

“Man for Himself: An Inquiry Into the Psychology of Ethics” (Erich Fromm)

Running Scared

One very promising approach to understanding many psychological problems is to look at them from an evolutionary perspective: to see if clinical observations can be re-framed around the evolution of the brain.

Our brains are a hodgepodge of bits and pieces that have evolved over millions of years. We still have regions that evolved in reptiles, as well as the stunningly complex neocortex that has been developing over the last few hundred thousand years. Most of the time the different systems and circuits cooperate, but that cooperation falls apart if people are under the influence of alcohol or dugs, or in different types of neurological and psychological problems. Then the older and more “primitive” regions of the brain take over. That is typically what happens when a drunk wants becomes irritable or wants to fight. It is also what can happen in people who have sustained damage or have abnormal development of the frontal lobes of the brain. Alternatively it may happen if something over-stimulates the primitive regions of the brain.

Colleagues in London have been doing experiments with a computer game that could be immensely valuable for people with panic attacks and some types of anxiety disorders.

Working with healthy volunteers, Dean Mobbs and colleagues at the Wellcome Trust Centre for Neuroimaging at University College, London, used a Pac Man-like computer game, in which subjects were chased through a maze by an artificial predator. If caught, they received a mild electric shock.

At the same time, brain scans measuring blood flow showed that when the predator was a long way off, lower parts of the prefrontal cortex area of the brain were active. This region is associated with complex decision-making, such as planning an escape.

But when the predator moved closer, activity shifted to the periaqueductal gray area, which is responsible for rapid response survival mechanisms such as fighting, flighting or freezing.

This shows us that the brain’s response to fear changes as a threat gets nearer: the more impulsive region takes over from the decision-making regions as a threat looms closer. A problem in the balance between the two regions could explain some anxiety disorders. Most sufferers report that they “know” that their fears are illogical, but they react anyway. So the key question is what is it that shifts the balance of activities between the forebrain and midbrain regions of the brain?

This new research is published in the journal Science, and builds on similar findings in animals, including tests on rats that were performed at the University of Colorado in Boulder and published in 2005. In those experiments rats with a non-functioning prefrontal cortex did not cope with stress as well as those with normal brains.

From an evolutionary perspective, maintaining the correct balance between the different regions of the brain that handle fear help animals to avoid or escape predators.

There are some situations where we only have to be wary about potential threats, but other times we need to react without thought. The closer a threat, the more impulsive will be your response. If the threat is large enough and close enough we lose any semblance of free will and just take action.

Just as happens when someone is in the throes of a severe anxiety attack.

Fears, Phobias, Posttraumatic Stress and Cortisol

If the prospect of standing up to speak in front of hundreds of people or the sight of a giant hairy spider has you quaking with fear, you may be surprised to learn that the cure may be a dose of the stress hormone cortisol.

In a study from the University of Zurich in Switzerland, Dominique de Quervain and his team gave either cortisol a.k.a. hydrocortisone, or its precursor, cortisone, to volunteers with arachnophobia – a fear of spiders – or phobias linked to social situations. A control group received a placebo. An hour later, the volunteers were confronted with a picture of a spider or given a public-speaking assignment. Their anxiety levels were evaluated both by heart rate and by asking them how they felt.

The people who had been given a dose of cortisol or cortisone were less anxious than those given the placebo. In the case of the people with arachnophobia, who had several testing sessions, fear levels dropped progressively with each session. In the placebo group, the volunteers who naturally had higher levels of cortisol were less anxious. The researchers concluded that the hormone damps down, rather than causes, the fear response.

This is in contrast to most theories that say cortisol triggers stress: it actually seems to be the other way round. Cortisol has a protective effect, a finding that could lead to new phobia therapies.

This finding follows the demonstration that cortisol may prevent the development of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) following critical illness and major surgery, probably by inhibiting the formation of traumatic memories.

This makes good sense. If you are exposed to acute stress the last thing that you want to have happen is to be hamstrung by constant intrusive memories of the event. By this line of reasoning, the question is instead why the system failed in people who went on to develop PTSD. It may be that the genetic component has something to do with a short circuit in this protective mechanism.