Imagination, Aspiration and Spirituality

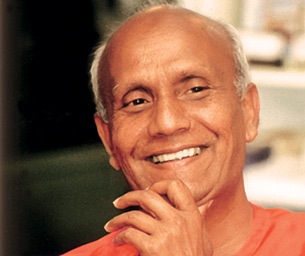

“Imagination plays a most significant role in the spiritual life. Suppose you are not having good meditations, but six months ago you had a very good, powerful, high meditation.

What you can do is try to imagine that powerful meditation. Then your imagination will become reality.

After fifteen minutes or half an hour, you will get a good meditation.

Vivekananda was such a great spiritual figure, yet sometimes for six months at a time he did not have a good meditation. What did he do? He used to imagine a time when he did have a good meditation, and inside his imagination was aspiration. So imagination is very good.”

–Sri Chinmoy (a.k.a. Chinmoy Kumar Ghose, Indian Philosopher and Spiritual Teacher, 1931-2007)

Meditate on a Flower

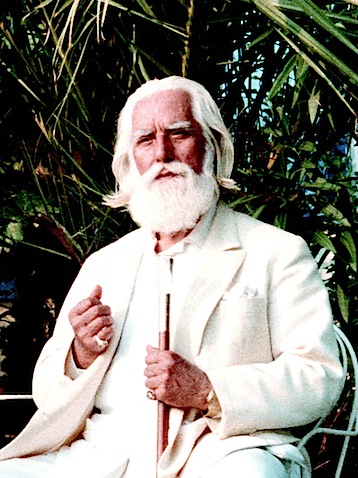

“We are in the habit of thinking of clothing as something we use to cover ourselves, but in fact there is much more to the matter.

It can be said that the physical body is the clothing of the soul and spirit, that words are the clothing of thought, and so on. Feelings, thoughts and forces have clothes, as do all creatures visible and invisible.

A flower, for example, is a garment in which an entity hides. This is why you must meditate on flowers, on their form, color and fragrance, so that you understand the nature of the beings who wear such clothing.

And it is not only on flowers that you must meditate, but on everything that exists in the different kingdoms of nature: mineral, vegetable, animal and human. A crystal, a diamond, a precious stone – each is a form of clothing, a body in which a spiritual entity has incarnated in order to reveal itself.”

–Omraam Mikhaël Aïvanhov (Bulgarian Spiritual Master, 1900-1986)

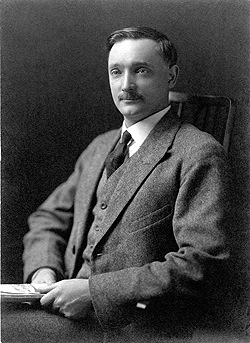

Steps Toward Knowledge of the One

“The three mental steps towards knowledge of the One Reality are:

1. Listening

2. Reflecting

3. Contemplating

Listening means paying attention to the statements of the Scriptures with reference to the One Reality, and also to the words of seers and sages on the subject.”

–Ernest E. Wood (English Theosophist, Yoga Practitioner, Translator, Author and Professor of Physics, Principal and President of the Sind National College and the Madanapalle College, India, 1883-1965)

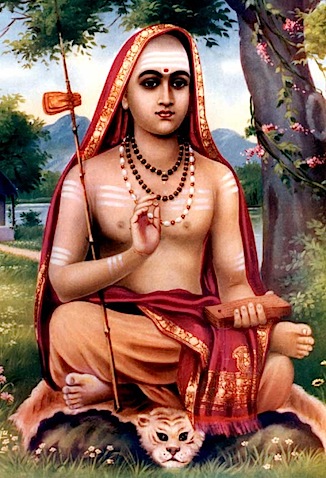

Entering Into Reality

“As gold purified in the furnace, rids itself of dross and reaches the quality of its own self, so the mind ridding itself of the dross of substance, force and darkness, through meditation, enters into reality.”

–Shankara (a.k.a. Adi Shankaracharya, Indian Sage, Spiritual Teacher and Author of the Crest-Jewel of Discrimination, Dates Uncertain, but c.A.D. 686-718 or 788-821)

Meditating On Good Thoughts

“The more man meditates upon good thoughts, the better will be his world and the world at large.”

–Confucius (Chinese Philosopher, 551-479 B.C.)

Meditation, Stress and Self-Regulation

There is progressively more evidence that meditation can have measurable effects on behavior and the brain. The trouble is that some of the results have conflicted, mainly because of the different types of meditation and different measurement protocols. So I was very interested to see some new research in this week’s issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, by a team of researchers from China collaborating with renowned experts at the University of Oregon, who have developed an approach for neuroscientists to study how very brief meditation training might improve a person’s attention and response to stress.

The study itself was done with undergraduate students in China. The experimental group received five days of meditation training using a technique called integrative body-mind training (IBMT), which was developed in China n the early 1990s.

IBMT is a rapid mental training method that aims at inducing a state of alert restfulness using breathing and guided imagery.

The control group received five days of relaxation training. Before and after training both groups took tests involving attention and reaction to mental stress.

The experimental group showed greater improvement a test of attention that was designed to measure peoples’ ability to resolve conflict among stimuli. Subjects were stressed by doing mental arithmetic.

At the beginning of the experiment both groups showed an elevated release of cortisol following the mathematical task, but after training the experimental group showed less cortisol release. This probably indicates an improvement in stress regulation. The experimental group also showed lower levels of anxiety, depression, anger and fatigue than the control group.

The next stage in the research will involve direct measurements of brain function.

Although IBMT is described as a form of meditation, it may be inducing something slightly different from, say, Zen meditation. The important point is that it is possible to produce measurable physiological changes in just five days, and this will make it much easier to examine the dynamic effects of hypnosis, relaxation and this technique on brain function.

I would also be grateful for any readers who have more information abut the precise details of IBMT, and whether training in the precise techniques is available outside China.

I shall keep you posted as new data emerge.

“Peace can be reached through meditation on the knowledge which dreams can give. Peace can also be reached through concentration upon that which is dearest to the heart.”

–Patanjali (Indian Philosopher said to be the Compiler of the Yoga Sutras, Dates Unknown)

“Through meditation and by giving full attention to one thing at a time, we can learn to direct attention where we choose.”

–Eknath Easwaran (Indian-American Spiritual Teacher, Professor and Author, 1910-1999)

“Meditation is not to escape from society, but to come

back to ourselves and see what is going on. Once there is

seeing, there must be acting. With mindfulness, we know

what to do and what not to do to help.”

–Thich Nhat Hahn (Vietnamese Buddhist Monk, 1926-)

“A meditator keeps his mind open every second. He is constantly investigating life, investigating his own experience, viewing existence in a detached and inquisitive way. Thus, he is constantly open to truth in any form, from any source, an at any time.”

–Henepola Gunaratana (a.k.a. Bhante G., Sri Lankan Buddhist Monk, 1927-)

Zen and the Aging Brain

The two main kinds of meditation that have received a lot of research attention are Zen and Transcendental Meditation. Both produce measurable physiological changes and both may produce changes in the brain.

Zen meditation is centered on attentional and postural self-regulation.

As we age, there is normally some decline of cerebral gray matter volume and attentional performance. As I have pointed out, those changes do not necessarily mean a decline in functioning, but simply a change.

In a new study researchers here in Atlanta examined how the regular practice of meditation might affect the brain. The researchers studied 13 regular practitioners of Zen meditation and 13 matched controls.

They used some sophisticated techniques to calculate the volumes of different regions of the brain. They also performed a computerized sustained attention task.

While the control subjects showed the expected negative correlation of both gray matter volume and attentional performance with age, the meditators did not show a significant correlation of either measure with age.

Interestingly, the effect of meditation on gray matter volume was most prominent in a region of the brain called the putamen, a system of the brain that is strongly implicated in attentional processing.

These findings are intriguing and are consistent with some of the research done in Richard Davidson’s laboratory in Wisconsin, that looked at people practicing a different form of meditation, but also showed that expert meditators produce both structural and functional changes in their brains.

The study on aging suggests that the regular practice of meditation may have neuroprotective effects and reduce the cognitive decline associated with normal aging.

If that is confirmed, I think that we have something else to add to our list of “things to do to reduce your risk of getting Alzheimer’s.”

Mindfulness and Depression

Mindfulness meditation has rightly been receiving a lot of attention recently. It is quite simply a technique in which you become intentionally aware of your thoughts and actions in the present moment, non-judgmentally. Though originally a Buddhist technique, it is something that can be practiced by anyone, and there are, in fact, similar techniques that have been developed by Christian mystics and Sufis.

It has recently been discovered that some of the techniques that were developed so that a mystic or meditator could carry on without distraction, may also have value in treating clinical problems. After all, if a group of people has spent a thousand years developing tools and techniques for managing the mind, it might be a good idea to see what they have discovered!

There have recently been several excellent books on the use of mindfulness in the management of depression:

The Mindful Way Through Depression

Relaxation, Meditation and Mindfulness

Mindfulness and Acceptance: Expanding the Cognitive-Behavioral Tradition

This whole field was moved forward by some research from San Francisco (NR822) that was presented at the end of May at the 2007 Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association in San Diego. The researchers used Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT) in a group of 53 people with treatment resistant depression.

MBCT is based on the Mindfulness-based Stress Reduction (MBSR) eight-week program that was developed by Jon Kabat-Zinn in 1979 at the University of Massachusetts Medical Center. Research has show that MBSR can be enormously empowering for people with chronic pain, hypertension, heart disease, cancer, and gastrointestinal disorders, as well as for psychological problems such as anxiety and panic.

Mindfulness-based Cognitive Therapy grew from this work. Zindel Segal, Mark Williams and John Teasdale adapted the MBSR program so that it could be used for people who had suffered repeated episodes of depression.

The results of the study presented in San Diego showed that MBCT was effective in reducing depression when compared to treatment as usual: what we call “TAU.” What seems to happen is that MBCT gives people a set of skills for detaching from the stream of depressive thoughts and feelings. As a result the symptoms decrease. Though the study will need to be expanded and replicated, this is clearly a fertile area for research.

This work is also interesting in the light of recent research showing that mindfulness training may improve the activity of some of the subsystems of the brain dedicated to attention, as well as helping some people with mental illness control their aggressive behavior. Mindfulness training may also help to reduce subjective reduces distress and improves positive mood states. It seems to be particularly good at reducing distracting and ruminative thoughts and behaviors.

And just for good measure, mindfulness may help some smokers quit.

“The purpose of meditation is not enlightenment, it is to pay attention even at extraordinary times, to be of the present, nothing-but-in-the-present, to bear this mindfulness of now into each event of ordinary life.”

–Peter Matthiessen (American Naturalist and Writer, 1927-)

“Meditation is not to escape from society, but to come

back to ourselves and see what is going on. Once there is

seeing, there must be acting. With mindfulness, we know

what to do and what not to do to help.”

— Thich Nhat Hanh Vietnamese Buddhist Monk, 1926-)

“Conscious means “having an awareness of one’s inner and outer worlds; mentally perceptive, awake, mindful.” So “conscious business” might mean, engaging in an occupation, work, or trade in a mindful, awake fashion. This implies, of course, that many people do not do so. In my experience, that is often the case. So I would definitely be in favor of conscious business; or conscious anything, for that matter.”

–Ken Wilber (American Philosopher, 1949-)

Non-pharmacological and Lifestyle Approaches to Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: 7. Yoga, Meditation and T’ai Chi Ch’uan

It may seem strange that someone with an attentional problem could sit still long enough to do yoga or meditation, but here is some evidence that they can do them and derive long term benefit.

Yoga

There are hundreds of different types of yoga, but the one that has been examined the most is hatha yoga. The first report of an improvement in ADHD symptoms with relaxation training including a yoga component was published in 1992. There is a small peer-reviewed study of yoga for children with ADHD. It was a six-week open trial of twice weekly hatha yoga lesson for both parents and children. The participants were also encouraged to practice at home. At the end of the six weeks, there were subjective improvements in behavior, and in those who practiced at home there was an improvement in emotional lability.

Another pilot study this time from Heidelberg in Germany suggested that yoga can be an effective complementary or concomitant treatment for ADHD. That was also the conclusion from a recent review article: yoga, like most of the other complementary methods of treatment, may be a good adjunct, but we do not have enough evidence to use it in place of existing treatments.

That being said, many experts and many yoga teachers consistently report that they have students who have improved very markedly when they follow a regular yoga regimen.

Meditation

Eugene Arnold’s excellent review of unorthodox treatments for ADHD cites two studies from the 1980s that showed significant improvements in the behavior of children who were taught to practice meditation. (Kratter J. The use of meditation in the treatment of attention deficit disorder with hyperactivity. Dissertation Abstracts International 1983;44:1965 and Moretti-Altuna G. The effects of meditation versus medication in the treatment of attention deficit disorder with hyperactivity. Dissertation Abstracts International 1987;47:4658.) Neither of the reports is easily available and the studies were not published in peer-reviews journals. A small six-week pilot study using Sahaja Yoga meditation for children with ADHD and their families reported a small but useful benefit.

Although there is not much published research on the use of meditation and ADHD, there are a great many anecdotal reports, and some good theoretical reasons for thinking that it should help. Research has shown that expert meditators produce both structural and functional changes in their brains, particularly in the regions involved in attention.

T’ai Chi Ch’uan

There are a large number of reports of people with ADHD improving if they practice t’ai chi or qigong, and in the days that I taught them, I have seen some remarkable improvements. But sadly there are few peer-reviewed studies in any of the languages that I can read.

There is a small but interesting study that was published in the Journal of Bodywork & Movement Therapies and involved 13 adolescents with an average age of 14.5 years. They were taught some basic t’ai chi moves for 30 minutes twice a week for five weeks. The sessions consisted of breathing exercises accompanied by slow raising and lowering of the arms, twisting and turning of the arms and legs, shifting body weight, rotating and changing direction.

The researchers used the 28-item Connors’ Teacher Rating Scale was used to evaluate their behavior prior to the tai chi classes, during the classes and two weeks after the classes ended. The adolescents’ teachers perceived them as less anxious, emotional and hyperactive. These improved scores remained consistent throughout the two-week follow-up period.

Given the anecdotal reports of the benefit of t’ai chi ch’uan and qigong on attention, concentration, depression and anxiety, it is important to do some more research on them n ADHD. In the meantime, there is no known downside of someone with ADHD using these practices in combination with more orthodox approaches.

And if they help, I would like to hear about it!

Meditation and Learning to Pay Attention

I have talked before about the increasing difficulties that we all have with paying attention.

Over the years we have tried all sorts of things to help people to become better at focusing and controlling their attention, from games, to biofeedback devices to meditation. It is the last of those that seems to be the most effective.

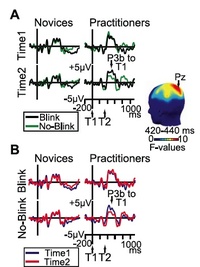

We know from personal experience that paying close attention to one thing can keep us from noticing something else. If we are shown two visual signals half a second apart, we usually miss the second because we are still focused on the first one. We are consciously unaware of the second flash. It is rather like missing something when we blink our eyes, and indeed psychologists call it “attentional blink.” Many psychologists have assumed that attention is something fixed: we can only give a certain amount of attention to one thing at a time before we have to move onto something else or get a kind of brain freeze.

But we have known for some time now that sometimes people do notice the second flash of light, and with practice they can notice it all the time, suggesting that the limitation on seeing the two flashes is not entirely physical, but that it may be possible to bring it under mental control. The first style of meditation that I ever learned was Vipassana, and I well remember being astonished at how quickly my attention and focus began to improve, even when I was not meditating.

Now there is an important new study from the University of Wisconsin-Madison that suggests that attention does not have a fixed capacity, and that it can be improved by directed mental training such as meditation.

The work was done in Richard Davidson’s lab at the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Medicine and Public Health and the Waisman Center for Brain Imaging and Behavior and published online in the journal PLoS Biology. (This is one of the growing number of open access journals, and for people not yet convinced of the value of open journals have a look at this paper, in which everything is available to you for free.)

The investigators recruited people who were interested in meditation to study whether conscious mental training can affect attention.

They examined the effects of three months of intensive training in Vipassana meditation, which focuses on reducing mental distraction and improving sensory awareness.

Volunteers were asked to look for target numbers that were mixed into a series of distracting letters and quickly flashed on a screen. As subjects performed the task, their brain activity was recorded with electrodes placed on the scalp. In some cases, two target numbers appeared in the series less than one-half second apart – close enough to fall within the typical attentional blink window.

The researchers found that the three months of rigorous training in Vipassana meditation improved people’s ability to detect a second target within the half-second time window. In addition, though the ability to see the first target did not change, the mental training reduced the amount of brain activity associated with seeing the first target.

Because the subjects were not meditating during the test, their improvement suggests that prior training can cause lasting changes in how people allocate their mental resources.

As Richard Davidson says,

“Their previous practice of meditation is influencing their performance on this task. The conventional view is that attentional resources are limited. This shows that attention capabilities can be enhanced through learning.”

The finding that attention is a flexible skill opens up many possibilities. It provides further evidence that attention training is worth examining for attentional problems such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

“When we raise ourselves through meditation to what unites us with the spirit, we quicken something within us that is eternal and unlimited by birth and death. Once we have experienced this eternal part in us, we can no longer doubt its existence. Meditation is thus the way to knowing and beholding the eternal, indestructible, essential center of our being.”

–Rudolf Steiner (Croatian-born Austrian Mystic, Occultist, Social Philosopher, Architect and Founder of Anthroposophy, 1861-1925)

“The moment one gives close attention to anything, even a blade of grass, it becomes a mysterious, awesome, indescribably magnificent world in itself.”

–Henry Miller (American Writer, 1891-1980)

“The path of spiritual attention is not easy, although anyone can make a beginning by trying to understand.”

— Sri Raghavan Iyer (Indian-born Prodigy, Rhodes Scholar, Academic, Philosopher, Theosophist, and, from 1965-1986, Professor of Political Science at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and Father of Pico Iyer, 1930-1995)